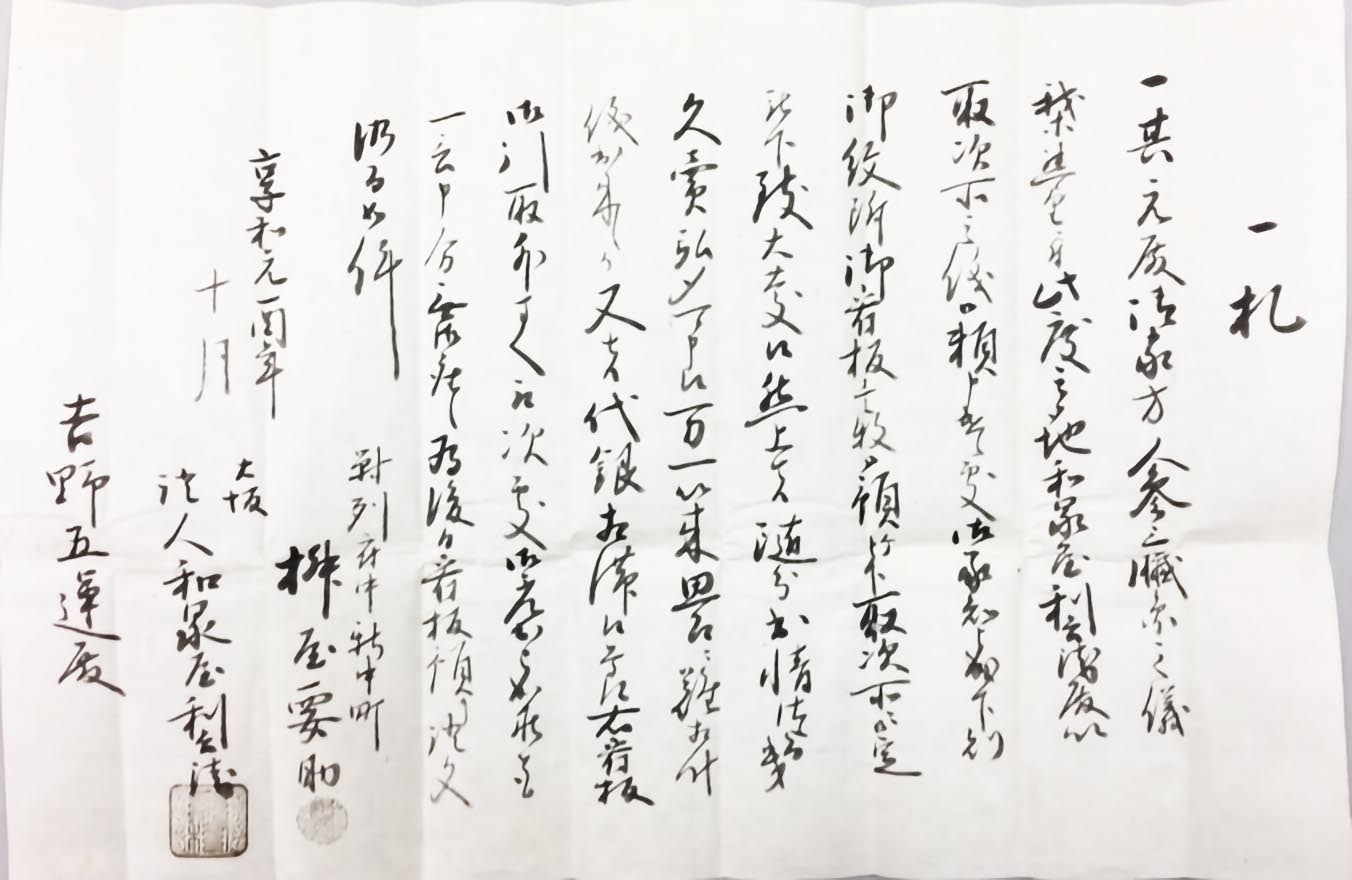

Hero Image: The Yoshino Goun monjo -Document 124-2, Issatsu,

owned by the Department of Japanese History, Osaka City University

吉野五運文書124-2、「一札」、大阪市立大学日本史学教室所蔵

Introduction

As the title of this series indicates, we will be exploring the world of social groups revealed in the historical documents (komonjo) left to us by the people of early modern Japan. Our guide, Dr. Watanabe Sachiko, will present an accessible introduction to the reading of Edo-period sources using the Yoshino Goun monjo, an archival collection held by the Japanese history division in the Department of Literature at Osaka City University.

The analysis proceeds methodically through the deciphering of the original handwritten documents, unpacking their dense style into “spoken” form (yomikudashi), and preparing a modern Japanese translation. The aim is to reconstruct the web of socio-economic relations constituted by the Yoshino Goun, a house of apothecary (gōyakuya), specifically their distribution and sales structures and the field of social groups tied into them.

As such, this series provides a concrete introduction to the agenda and methods early modern Japanese urban social history, which aims to bring to light, in fine detail, the world of these social groups. We very much hope that the series will find wide readership among those with an interest in the history of the Edo period and its rich legacy of komonjo.

The Yoshino Goun Documents (Part 3) – Dr. Watanabe Sachiko

Continuing on from last time, today we will look at the placard deed in more detail. Please refer to the original text, yomikudashi-bun, and modern Japanese translation from Part 2 as necessary.

First, the document tells us that because Masuya Yōsuke wanted to start dealing in the ninjin sanzōen medicine produced by Yoshino Goun, he went through Izumiya Rihē to apply to become an official dealer. From this, we can unpack some important details:

- In the text, we see that Masuya Yōsuke wanted to stock Yoshino Goun-“hō” (方) ninjin sanzōen; here hō refers to the composition, or formula, of the medicine (as in mod. Japanese shohō, or prescription), meaning Yōsuke wanted a ginseng medicine called ninjin sanzōen made in a way specific to the Yoshino Goun house.

- He wants to become a toritsugisho (取次所; outlet, dealer/retailer) for that medicine. A toritsugisho does not produce anything; it is a store that orders and sells a particular product that somebody else produces, much like modern outlets for a chain or brand.

- In other words, Yōsuke will be selling gōyaku (合薬), the finished medicinal product of a manufacturer, in this case Yoshino Goun. Yōsuke’s skill and knowledge in medicine are not at issue the deed, so these were not required for him to become a dealer.

- To become a dealer, one had to apply through a shōnin (証人; witness, intermediary). In this case, Izumiya Rihē was a resident of Osaka. There was no way Yōsuke, a resident of Tsushima Province (present-day Tsushima City, Nagasaki Prefecture) could apply to the house of Yoshino Goun without an introduction, so we can assume Rihē exerted a great influence over the application process. The connection between the two men is unclear, but we can imagine several possibilities: they might have been related or had previous business dealings with each other, or Rihē might also have been from Tsushima.

Moving on to the next part of the document, evidently the Yoshino Goun approved Yōsuke’s application, entrusted him with a placard bearing the house seal, and registered him as a dealer. Again, we can use these basic facts to ask questions and make inferences:

- What informed Yoshino Goun’s approval of Yōsuke’s application? Likely the house saw merit in the new revenue stream that would come online if they had a dealer selling their product in a place as far removed from Osaka as Tsushima; however, precisely because of the distance involved, they would have had consider all the more carefully whether they could trust this new commercial partner to forward sales revenue honestly, etc.

- We do not know much concrete about the placard entrusted to Yōsuke, save that it bore the Yoshino Goun house crest; in any case, it would have advertised the medicine’s name (ninjin sanzōen) and that Yoshino Goun supplied the merchant displaying it, who could therefore conduct business as a legitimate dealer. Also, because the placard was only “entrusted” (azuke) to Yōsuke’s keeping, we know it remained Yoshino Goun property.

In the final lines of the deed of entrustment, we have the promises to work diligently to sell the medicine and not to bring any complaints if the placard was confiscated and given to another merchant owing to delinquent payments or other occurrences not in keeping with Yoshino Goun’s expectations. One more time, let us explore the implications here:

- The placard had to be returned if the dealer did not or could not forward sales revenue. This underlines what we just established above: Yoshino Goun owned the placard, and it could be taken back at any time should a problem arise.

- Next, the possibility of establishing a new dealer appears in the text as hokakata e toritsugisho sashidashi, giving the sense that the house would present (sashidasu), or hand over, the confiscated placard to that other person. We can see, then, that whomever was entrusted with the placard could begin operating as a dealer, which fits with the document’s being referred to in the text as a “placard-holding deed” (kanban azukari shōmon).

- Finally, because the house of Yoshino Goun ultimately remained the owner of the placards it issued, we can see the strength of its position vis-à-vis its dealers.

After reading through the document in this manner, we have established that in applying for and being granted a dealership, Masuya Yōsuke:

- was a merchant from far away and so used a guarantor in Osaka

- did not himself have knowledge of how to make drugs

- engaged in business as a borrower of the placard

There were many other such merchants who sought to deal in Yoshino Goun’s ninjin sanzōen.

Next time we will look into just how extensive the house’s network of dealers was.