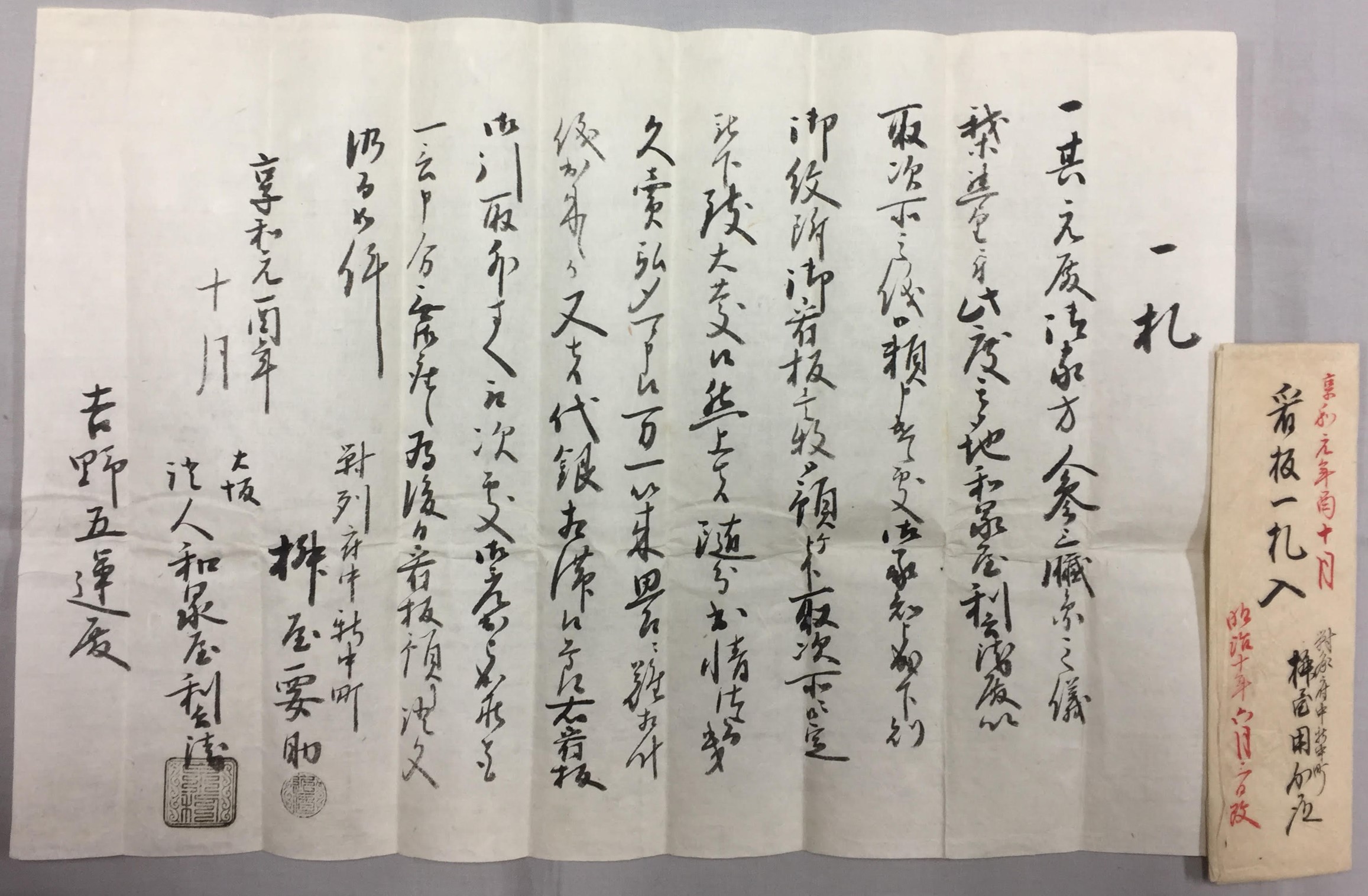

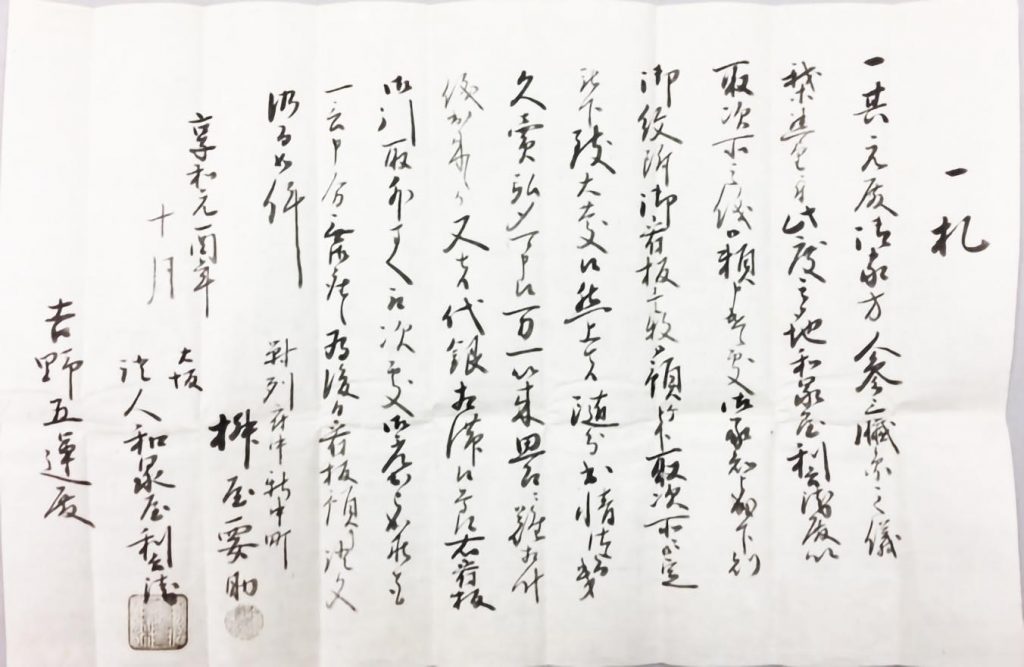

Hero Image: The Yoshino Goun monjo -Document 124-2, Issatsu, / Document 124-1, Paper Envelope

owned by the Department of Japanese History, Osaka City University

吉野五運文書より「一札」(124-2)およびその包紙(124-1)、

大阪市立大学日本史学教室所蔵

Introduction

As the title of this series indicates, we will be exploring the world of social groups revealed in the historical documents (komonjo) left to us by the people of early modern Japan. Our guide, Dr. Watanabe Sachiko, will present an accessible introduction to the reading of Edo-period sources using the Yoshino Goun monjo, an archival collection held by the Japanese history division in the Department of Literature at Osaka City University.

The analysis proceeds methodically through the deciphering of the original handwritten documents, unpacking their dense style into “spoken” form (yomikudashi), and preparing a modern Japanese translation. The aim is to reconstruct the web of socio-economic relations constituted by the Yoshino Goun, a house of apothecary (gōyakuya), specifically their distribution and sales structures and the field of social groups tied into them.

As such, this series provides a concrete introduction to the agenda and methods early modern Japanese urban social history, which aims to bring to light, in fine detail, the world of these social groups. We very much hope that the series will find wide readership among those with an interest in the history of the Edo period and its rich legacy of komonjo.

The Yoshino Goun Documents (Part 2) – Dr. Watanabe Sachiko

In this installment, continuing our introduction to the Yoshida Goun monjo (YGM), we will go through a complete example document. As discussed last time, the collection contains a set of just over one hundred similarly formatted contracts. To determine what kind of contracts they are and why they were preserved together, first we must decipher the text. We break up the work into three distinct steps, which helps us catch different types of errors and facilitates consultation with other scholars.

First we transcribe the original document’s handwritten cursive characters (kuzushi-ji) into print characters (katsu-ji):

Yoshino Goun monjo – Document 124-2

一札

一、其元殿御家方、人参三臓円之儀、我等懇望に付、此度其御地和泉屋利兵衛殿以、取次所之儀、御頼申遣候処、御承知被成下、則御紋付御看板壱枚御預け被下、取次所に御定被下、致大慶候、然上は随分出情仕候て、幾久売弘め可申候、万一、以来思召に難相叶儀出来候か、又は代銀相滞候節、右看板御引取、外方へ取次処御差出被成候とも、一言申分無御座候、為後日看板預り証文仍て如件、

享和元酉年

十月対州府中新中町

枡屋 要助(印)大坂

証人 和泉屋 利兵衛(印)吉野五運殿

The original document is written in sōrō-bun, a compact epistolary style distinguished by two main features: 1) hiragana and katakana generally appear very sparingly because phonetic verb tails (okurigana) and grammatical particles are often dropped (also, adpositions that do appear, along with many conjugative/honorific verbal elements, are often replaced by kanji); 2) said particles and verbal elements are regularly condensed into Chinese style (kanbun), i.e., placed at the head of their grammatical phrases rather than the rear as in spoken Japanese (in the above text, examples of 1 are underlined and 2 written in red). Therefore, the next step is to unpack the text into spoken form (yomikudashi-bun):

Spoken Form

一つ、そこもと殿御家方、人参三臓円の儀、我等懇望につき、このたびその御地和泉屋利兵衛殿(を)もって、取次所の儀、御頼み申し遣わし候処、御承知成し下され、すなわち御紋付御看板一枚御預け下され、取次所に御定め下され、大慶致し候、しかる上は随分出情つかまつり候て、幾久売り弘め申すべく候、万一、以来思し召しに相叶いがたき儀出来候か、又は代銀相滞り候節、右看板御引き取り、外方へ取次処御差し出し成され候とも、一言申し分御座無く候、後日のため看板預り証文、よって件のごとし、

(日付・差出人・宛先は省略)(Date, sender, addressee abbreviated)

Last, we render our reading of the text into modern Japanese:

Modern Japanese

一札(=一通の書付)

あなたの家で作っている人参三臓円(の商売)を、私は強く望んでいるので、このたびそちら(=大坂)の和泉屋利兵衛殿から、取次所について頼ませたところ、承知してくださって、御紋付の看板一枚を預けてくださって、取次所に定めてくださって、たいへん喜ばしく思います。これからはできるだけ精を出して、末永く売り弘めを致します。万一、これから後に、お考えにそぐわないことが生じるか、または代銀(の支払い)が滞った時には、右記の看板を引き取り、他のところへ取次所を出されても、一言も不満を申しません。後日のため、看板預りの証拠となる文書は、このとおりです。

| 享和元年(1801年) 酉年十月 |

対州(対馬国)府中新中町 枡屋 要助(印) |

||

| 大坂 証人 和泉屋 利兵衛(印) |

|||

| 吉野五運殿 | |||

Using the modern Japanese, let us confirm the main points of the contract, which the sender, Masuya Yōsuke, submitted to the house of Yoshino Goun on becoming a licensed distributor of a ginseng medicine they produced (ninjin sanzōen): first, he applied for license through the good offices of Izumiya Rihē of Osaka; upon being granted such, he took a placard for that medicine into his keeping; finally, in cases of delinquent payments to the house or other unforeseen difficulties, he promised not to bring any complaints should the placard be confiscated and granted to some other distributor.

The fact that so many of the same type of contracts have been preserved provides a sense of the extent of Yoshino Goun’s distribution network for their ginseng medicine. In the next part of this series, we will go deeper into the contents of the contract to consider what exactly a distributor was and what kind of person could become one.