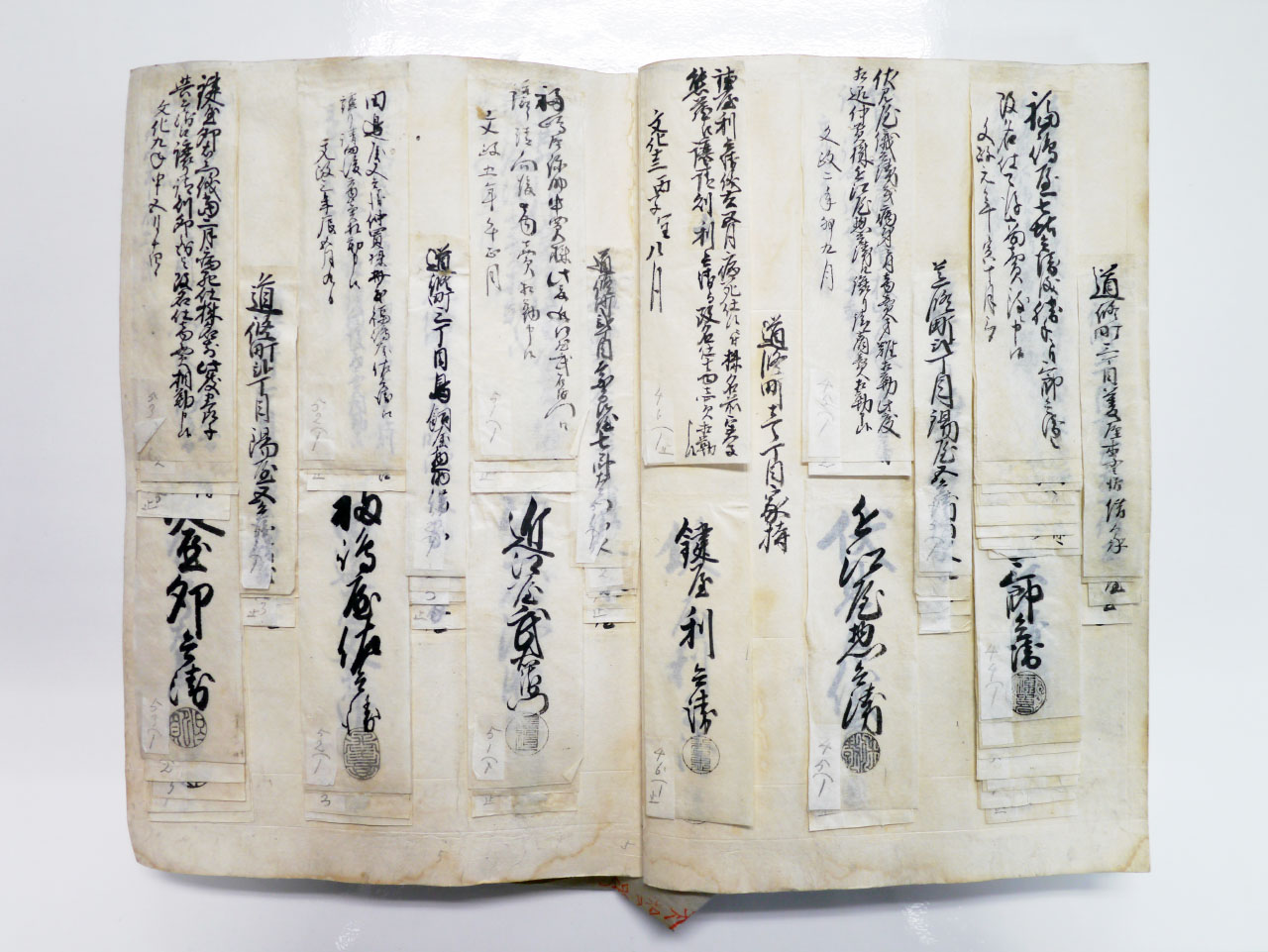

Hero Image: the Doshōmachi Fraternity Documents

Owned by the Doshōmachi Pharmaceutical Archive

道修町文書 くすりの道修町資料館所蔵

Introduction

During last session, we examined the urban neighborhood (association), which served as the basic unit of daily life in the early modern city. In our analysis, we focused on the case of Osaka’s Doshōmachi 3-chōme neighborhood. During this session, however, we will examine another important urban social organization, the fraternity (nakama). In addition to the licensed occupational fraternities established by merchants and artisans, members of the hinin and kawata status groups, performers, and religious practitioners also formed self-governing fraternal organizations. An 1808 record from the Osaka City Governor’s Office contains a comprehensive list of all of the city’s late Edo-era occupational fraternities. It includes fraternities that engaged in the distribution of goods, including fish, produce, rice, materia medica, and oil brokers and wholesalers, fraternities that engaged in financial activities, such as money changing and pawn broking, and fraternities whose members engaged in the provision of a specific service, including teahouses, bathhouses, and inns. As the list indicates, a large number and diverse array of fraternal organizations existed in early nineteenth-century Osaka. This week, we will focus on the case of Osaka’s Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild. The members of Osaka’s Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild lived together in the Doshōmachi 1-chōme, 2-chōme, and 3-chōme neighborhoods.

1. What is a Licensed Fraternity?

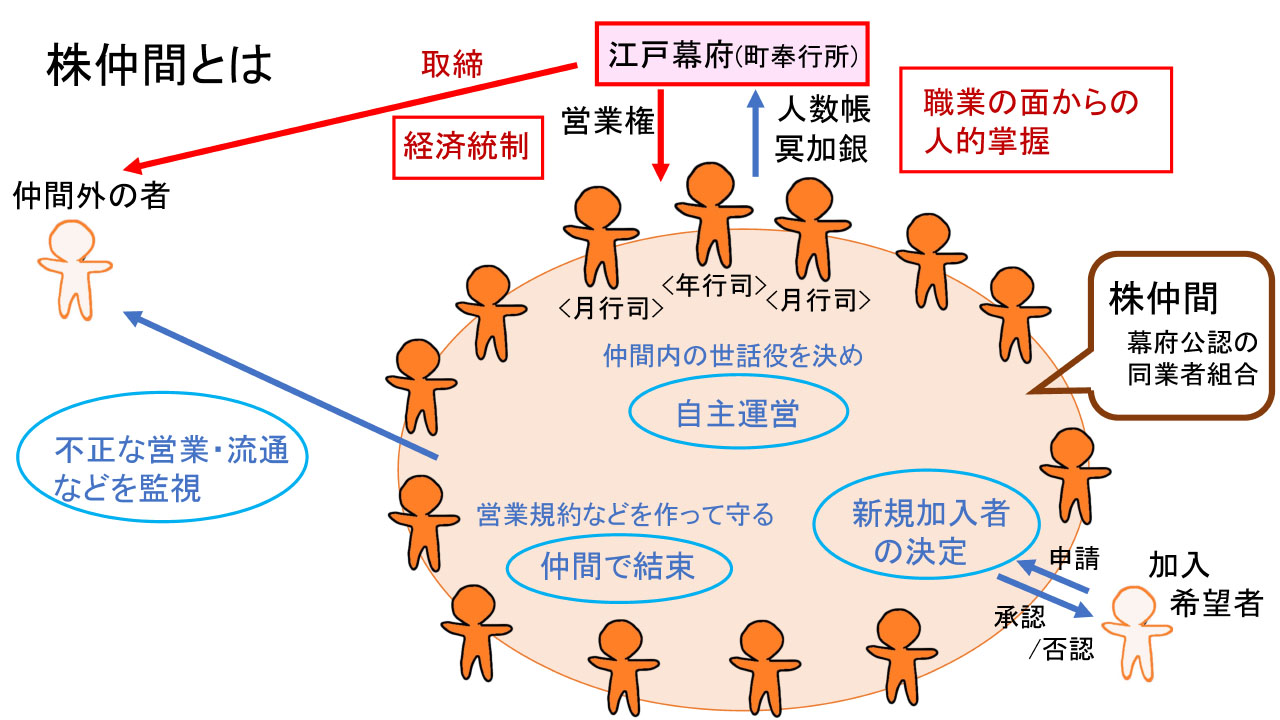

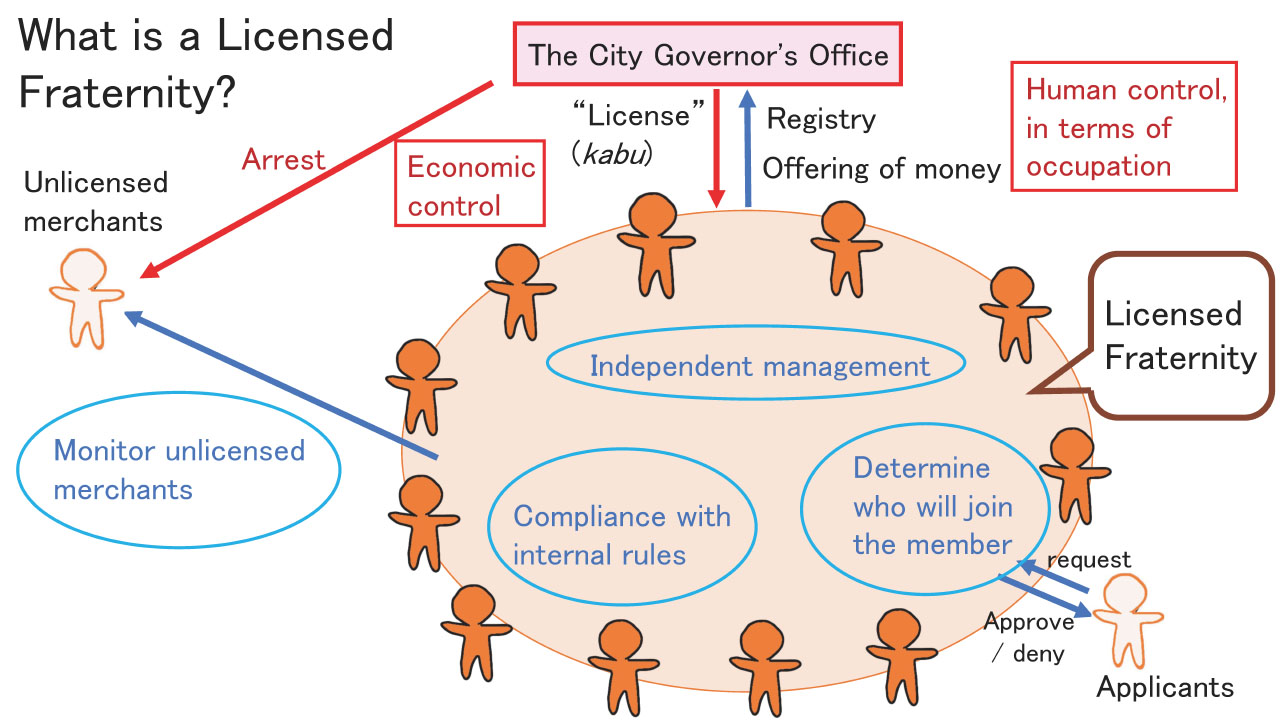

The term “licensed fraternity” (kabu nakama) refers to an association of individuals who own a specific sort of occupational license. Generally speaking, the term “license” (kabu) can be understood as the right to engage in a specific trade. Although there were some exceptions, the number of licenses for most trades were restricted. Under the early modern fraternity system, the right to engage in a specific trade was, as a general rule, limited to the licensed members of officially-sanctioned occupational fraternities. At the same time, unlicensed merchants and artisans were, in principle, excluded from fraternal organizations and prohibited from plying their trade without proper certification. Of course, an examination of actual economic activity reveals that the engagement of unlicensed actors (shirōto) in various trades was unavoidable. Licensed occupational fraternities, which were officially sanctioned by the Bakufu, made monetary offerings to the authorities. By doing so, the members of those fraternities sought to engage the Bakufu in the regulation of unlicensed competitors. At the same time, the Bakufu attempted to regulate merchants and artisans using the framework of the licensed fraternity.

During the first half of the early modern period, fraternal organizations developed within individual professions. However, it was only in the mid-eighteenth century that the Bakufu began sanctioning such organizations on a broad scale. In 1842, however, the Bakufu issued the Edict Disbanding Licensed Fraternities. That Edict was one of the key economic policies implemented during the Tenpō reforms and was intended to lower commodity prices. It was short-lived, however, as fraternal organizations were reestablished in 1851. Despite that fact, we cannot overlook the vigorous and wide-ranging economic activities in which merchants and artisans traditionally unaffiliated with occupational fraternities engaged between 1842 and 1851. During that brief period, there were no limits on the number of individuals who engage in a given trade and many formerly unlicensed actors thrived.

As in the case of urban neighborhoods, licensed occupational fraternities established independent organizational regulations. In addition, although the structure of these fraternities varied depending on the occupation, officers, including annual and monthly representatives, were appointed to administer fraternity affairs and regulate fraternity constituents. In order to further our analysis of these fraternal organizations, let us now examine the case of Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild.

2. The Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild

In Doshōmachi 2-chōme, there is a Shinto shrine known as Sukunahikona Shrine, or Shinnō-san. Enshrined there is the Chinese god of medicine, Shinnō (Shennong). The shrine is located on the former site of the Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild Office. It was established in 1780, when the Shinnō deity was transferred to Doshōmachi from Kyoto’s Gojōten Shrine. Even after the transfer, however, the shrine grounds continued to serve as the location of the Guild Office. A massive volume of documents produced by the Guild were stored, during the Edo period, at the Guild Office. Many of those documents have been carefully preserved and are currently displayed at the Doshōmachi Pharmaceutical Archive.

During the second half of the seventeenth century, materia medica merchants gathered in the Doshōmachi area. Unlike retailers that sold oral medicines and ointments, however, the merchants in Doshōmachi did not sell market-ready drugs. Rather, they bought and sold materia medica used to produce herbal medicines. During this period, those ingredients were mostly foreign in origin, imported from the Asian mainland via Nagasaki. Entering the eighteenth century, however, domestic producers from across Japan began manufacturing medicinal ingredients. Domestically-produced ingredients circulated under the name Japanese materia medica (wayakushu). In 1722, the Bakufu established the Regulatory Office for Domestic Medicines in order to ensure the quality of domestically-produced materia medica and prevent the circulation of fake medicines and poisonous pharmaceuticals. In Osaka, the city’s 124 licensed materia medica wholesalers, who possessed the ability to evaluate the quality and safety of materia medica, were appointed to administer the local Regulatory Office for Domestic Medicines. In conjunction with their appointment, the Doshōmachi Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild received official sanction from the Bakufu. What is more, the Guild remained in place even after the Regulatory Office for Domestic Medicines was abolished in 1738.

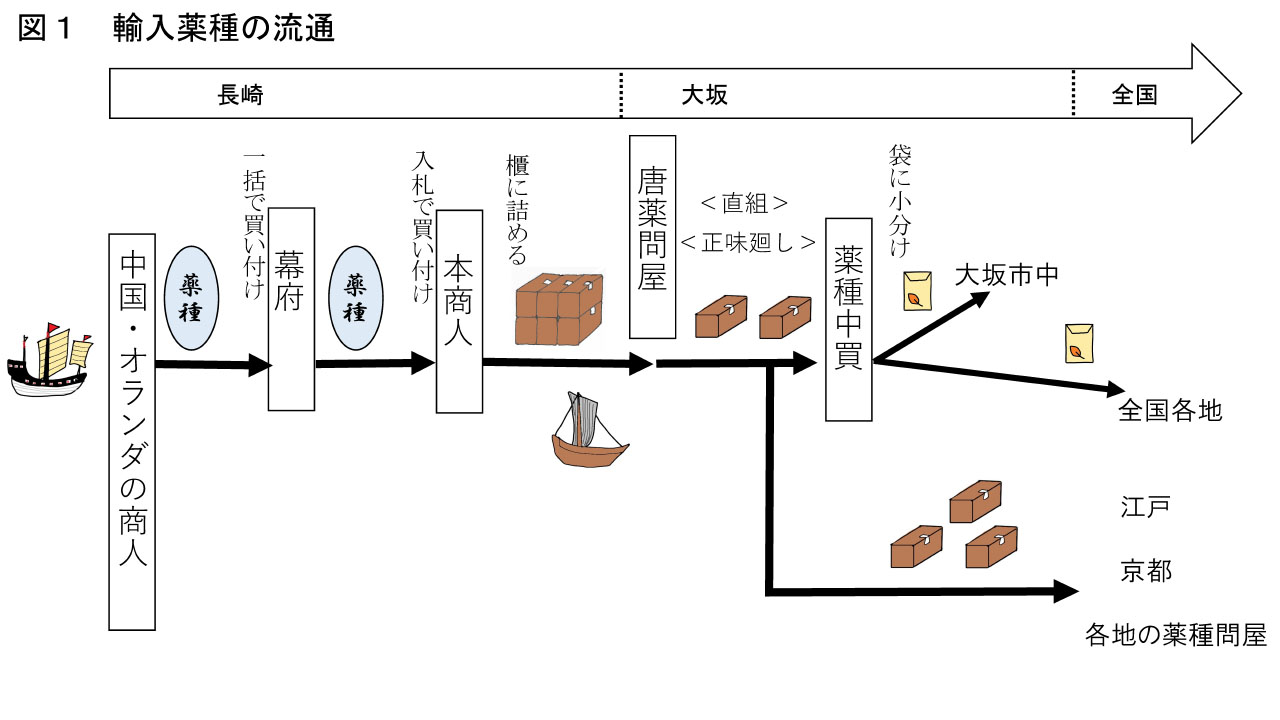

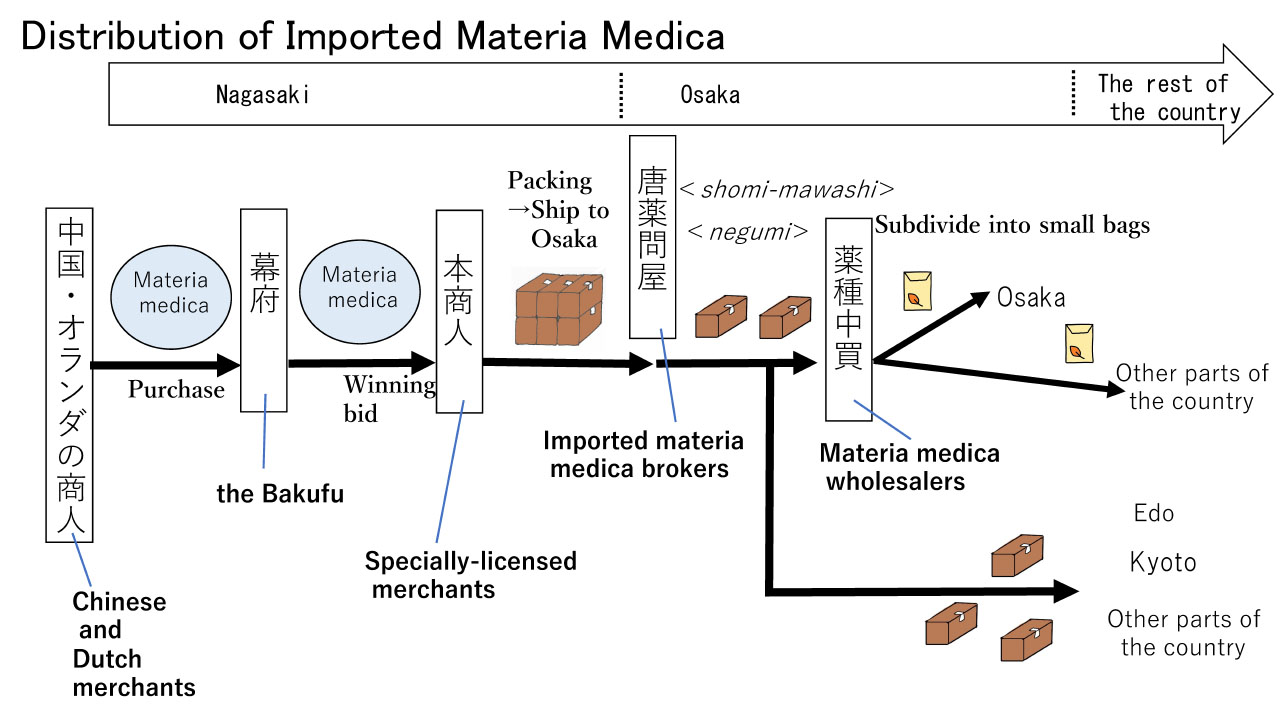

Now let us examine the role that Osaka’s materia medica wholesalers played in the distribution of materia medica during the Edo period. Please examine this diagram, which explains how imported materia medica were distributed during the early modern period.

All of the materia medica imported to Nagasaki were purchased by the Bakufu. They then auctioned off the ingredients to a group of specially-licensed merchants at a facility known as the Nagasaki Kaisho. These specially-licensed merchants were from five cities: Sakai, Nagasaki, Kyoto, Edo, and Osaka. They were granted special licenses during the early Edo period under the auspices of the Bakufu’s importation system. Under that system, access to foreign goods was limited to a select group of influential merchants. There were approximately 15 such merchants from Osaka. Nearly all of the materials purchased by those specially-licensed merchants were shipped to licensed brokers in Osaka who mediated the sale of imported materia medica. Those brokers then sold off those materials to wholesalers in Osaka and materia medica brokers in Edo and other parts of the country. Importantly, Osaka’s materia medica brokers only mediated the sale of the medicinal ingredients. They did not buy and sell the materials they brokered. In addition, Osaka’s materia medica brokers mediated the exchange of a variety of imported goods, not just medicinal ingredients. Those brokers established an occupational fraternity known as the Fraternity of Imported Materia medica Brokers, which was comprised of approximately 200 licensed members. Osaka’s materia medica wholesalers purchased imported materia medica from these brokers in units contained in wooden chests, which were known as hitsu. After ascertaining the quality of the ingredients, wholesalers then broke them down into smaller portions and sold them to retailers in Osaka and other parts of the country.

As noted above, Osaka’s imported materia medica brokers were simply mediators. They received chests containing medicinal ingredients from specially-licensed merchants who traveled to Nagasaki and then passed them on without alteration to wholesalers, who were the actual buyers. Unlike wholesalers, therefore, these pharmaceutical brokers did not possess the ability to evaluate the quality of the medicinal ingredients they were sent. When wholesalers came to purchase ingredients, the average weight of individual portions was determined using a method known as shomi-mawashi and the base price was set using a method known as negumi. These were important decisions which affected methods of exchange and market prices around the country. As this suggests, the Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild played a key role in the distribution of imported materia medica. Although the members of the Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild also played an important role in the exchange of domestically produced medicinal ingredients shipped to Osaka, I will not be discussing that role in detail here.

3. The Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild and Archival Records

As I mentioned above, the Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild left behind a wide vast collection of archival records. Currently, that collection contains more than 30,000 documents. I will introduce some of them.

owned by the Doshomachi Pharmaceutical Archive

This is a document entitled “A Registry of Licensed Materia Medica Wholesalers” from the twelfth month of 1799. Occupational fraternities that were officially sanctioned by the Bakufu produced registries in which they explained the series of events leading up to and events surrounding their sanctioning, and listed important regulations that their constituents were required to uphold. These registries were sealed by all licensed members of the fraternity and submitted to the City Governor’s Office. In addition, fraternity members prepared a second copy which was stored in the fraternity’s office. The Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild was no exception. Their registry explains that the Guild received official sanction in Kyōhō 7 (1722) in conjunction with the establishment of the Regulatory Office for Domestic Medicines. In addition, it contains a list of regulations concerning the handling of domestic materia medica, noxious medicines, and fake materia medica.

Initially, there were 124 licensed members of the Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild. However, at the time that this registry was composed, the authorities granted the Guild five additional licenses. As a result, it contains 129 signatures. In addition, the registry has been amended using notes, which detail changes in the ownership of licenses resulting from succession and exchange. Also, adult proxies commonly signed these registries when the owner of a license was still too young to do so themselves. Accordingly, this registry contains a series of corrections indicating a change of proxy or a change of residence on the part of the license’s owner. As time passed, the number of corrections would gradually increase. As a result, fraternity registries quickly became unmanageable. Consequently, fraternities produced new registries once every 15 to 20 years. New registries, such as the one composed in 1722, were then submitted to the City Governor’s Office.

Even though the record in question is a registry of licensed materia medica wholesalers, it is similar to cadastral registers produced in urban neighborhoods, which were updated, when a residential tract exchanged or inherited, using written notes. In addition, like neighborhoods, fraternities produced their own internal regulations. The Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild formulated its owned internal agreements and regulations. Take for example this record entitled “A Record of Agreements about Various Matters”. I would like to focus on the section that discusses the seventh month of 1752. It contains the following regulation. “When a licensed wholesaler attempts to establish a new operation and there are no spaces available along Doshōmachi Boulevard between Doshōmachi 1-chōme and 3-chōme, that individual should be permitted, for the time being, to set up shop along one of the area’s side streets. However, once a space opens up along Doshōmachi Boulevard, they should relocate there immediately.” As this section indicates, all licensed materia medica wholesalers were required to live in the three neighborhoods of Doshōmachi 1~3-chōme. Furthermore, as a general principle, they were required to live along the area’s main thoroughfare, rather than a side street. For the members of fraternal organizations, it was generally better, from a business perspective, to live along a busy street. In the case of the Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild, however, a policy of concentrated residence was strictly enforced. This was because the business activities of Guild members were carried out within a carefully constructed framework of mutual regulation. As persons engaging in the same occupation, the Guild’s members had a shared interest. Relations within the Guild, however, were more complex. Members engaged in relations of mutual exchange in which both the buyer and seller were licensed materia medica wholesalers. Accordingly, a certain degree of mutual caution was essential. As a consequence, wholesalers formed individualized commercial networks based on kinship relations. Those networks centered on a main household, which was a materia medica wholesaler, and included branch households, some of which engaged in related occupations.

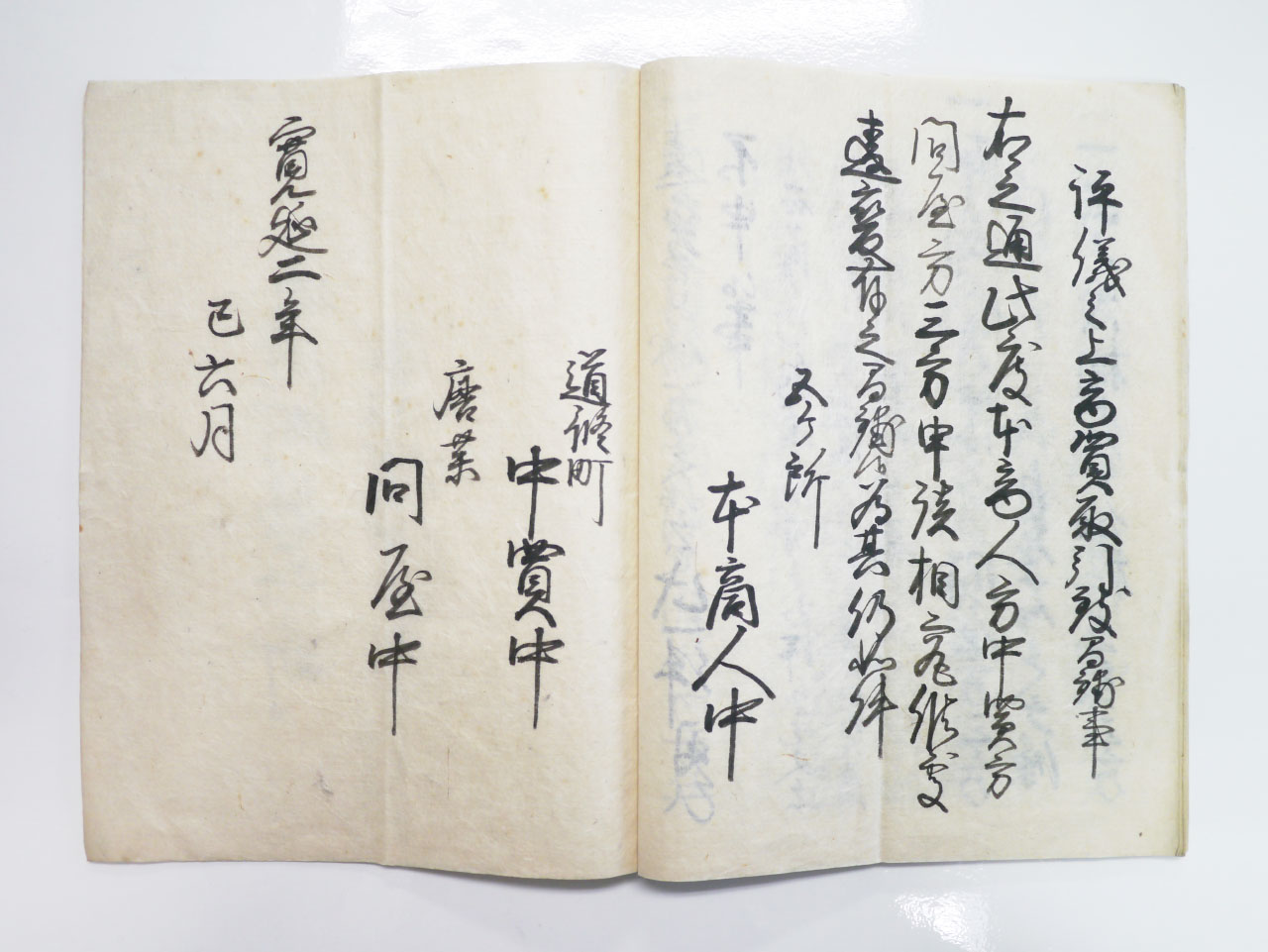

In addition, the documents produced by the Materia Medica Wholesalers’ Guild include regulations which were intended to structure relations with actors from outside the fraternity. For example, there is a record from 1749 entitled “The Triparty Articles of Agreement.”

owned by the Doshōmachi Pharmaceutical Archive

The end of that document contains the following passage. “At this time, the following articles of agreement have been established on the basis of a consultation between three parties, specially-licensed merchants, brokers, and wholesalers. Accordingly, they must be upheld by all concerned parties.” In addition, the document is signed by the members of all three groups. Notably, this document does not contain comprehensive regulations intended to control exchange between the three parties. Rather, it primarily contains rules concerning matters which could easily lead to disputes between the parties, such as methods for measuring the weight and setting the price of materia medica, and for handling of small amounts of leftover ingredients.

The three groups mentioned above were bound closely together in a network related to the distribution of imported materia medica. At the same time, however, there were instances in which the interests of the three groups collided. It is likely that the above agreement was concluded in an effort to resolve such clashes. Occupational fraternities really did produce a vast array of internal records. What is more, they were stored and managed at an independent fraternity office.

4. Summary

As I mentioned at the beginning of today’s lecture, if you visit Doshōmachi today, you quickly notice a large number of building containing pharmaceutical companies. While Osaka’s materia medica brokers simply mediated the sale of medicinal ingredients, the city’s early modern materia medica wholesalers attained the ability to evaluate the quality and safety of medicinal ingredients. Entering the Meiji period, that ability ultimately helped them to establish modern pharmaceutical companies.

During the past four sessions, we examined the structural characteristics of early modern Osaka. We did primarily through the analysis of basic social organizations of which city residents were part. As we observed, those organizations left behind a wide array of internal records, which tell us much about the lives and livelihoods of ordinary city dwellers. In addition, we examined the spatial structure of the Dōtonbori area and discussed its emergence as a bustling center of amusement. Both Dōtonbori and our focus the last two sessions, Doshōmachi, are parts of the city with an intimate connection to contemporary urban society. During the weeks ahead, you will learn about the historical trajectory of these social organizations and the transformation of the city’s spatial structure from the Meiji period onward. In other words, upcoming sessions will discuss the modernization of the traditional city of Osaka. I hope that you enjoy the lectures.