Hero Image: Black Market (Yami-ichi) in Umeda owned by Osaka Museum of History

梅田の闇市、大阪歴史博物館所蔵

Introduction

Hello, I’m Saga Ashita from OCU.

Today is the last lecture on the modern period, so we’ll be going on a whirlwind tour of urban Osaka’s history, from the wartime and postwar years all the way up to the contemporary period. Since this will also be the final class in the course, I’d also like to take a look at where Osaka, presently at a turning point, might be headed in the future, using the perspectives that have informed our analysis of the sweep of history we’ve covered since the ancient period.

As we discussed last class, by 1925 Osaka had gone “big time”, becoming Japan’s largest city in 1926 (the first year of Showa) while implementing its progressive urban policies. However, this was also a time of darkness: from late 1920s, Japan began its slide towards military intervention in China, which became a headlong rush into the Pacific War as it made enemies of Great Britain and the United States, ultimately engulfing Asia in calamity and destroying its own empire. To begin, let’s look at the path the city of Osaka and its citizens ended up taking through this age of war.

1. Wartime Osaka and Persistent Urban Problems

In 1930, on the eve of the Manchurian Incident (September 1931), Japan was still mired in the recession that had begun with Showa Financial Crisis of 1927. It was a bad year for Osaka, too, as business failures and poverty tightened their grip on the city. During these years, Osaka had the largest number of unemployed people of any city in Japan. Particularly hard hit were ethnic Koreans in Japan (Zainichi Chōsenjin), whose numbers grew from around this time even as they lived cheek to jowl in the worst areas of the slums, doing hard labor for poverty wages. There were of course many other poor people besides, and substandard housing districts only increased in number over the 1930s. However, despite the recession, Osaka never stopped growing because people continued to flow in from the countryside (where conditions were even worse), especially when the urban economy began to recover around the middle of the decade. In fact, Osaka’s population peaked around 1940 at approximately 3.25 million (2.7 today), a record that will likely never be broken.

| Dstrict | 1925 | 1930 | 1935 | 1940 | Percentage Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osaka City (total) |

2,114,804 | 2,453,573 | 2,989,874 | 3,252,340 | +53.8 |

| Old City Areas |

1,331,984 | 1,435,936 | 1,610,124 | 1,544,739 | +16.0 |

| Newly Incorporated Areas |

782,820 | 1,017,637 | 1,379,750 | 1,707,601 | +118.1 |

*Old City Areas (wards): Kita-ku, Konohana-ku, Higashi-ku, Nishi-ku, Minato-ku, Taisho-ku,Tennoji-ku, Minami-ku, Naniwa-ku

*Newly Incorporated Areas: Higashiyodogawa-ku, Nishiyodogawa-ku, Higashinari-ku,Asahi-ku, Sumiyoshi-ku, Nishinari-ku

The figure based on New Edition Osaka City History, Vol. 7, The Office of the Editor for Osaka City History

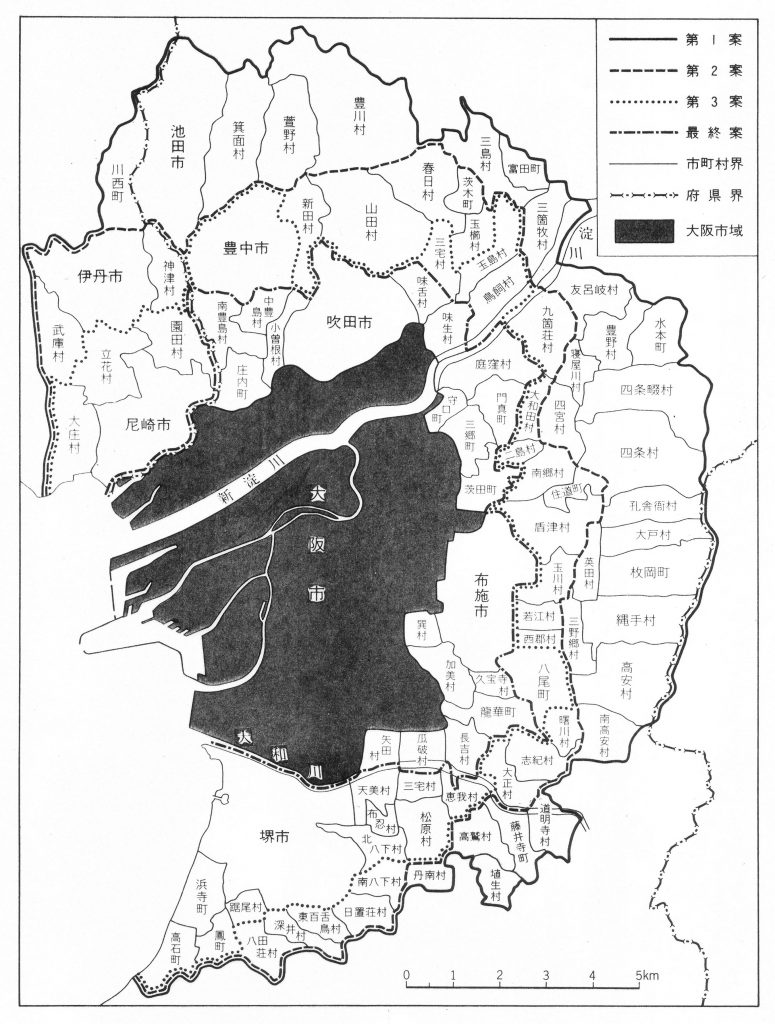

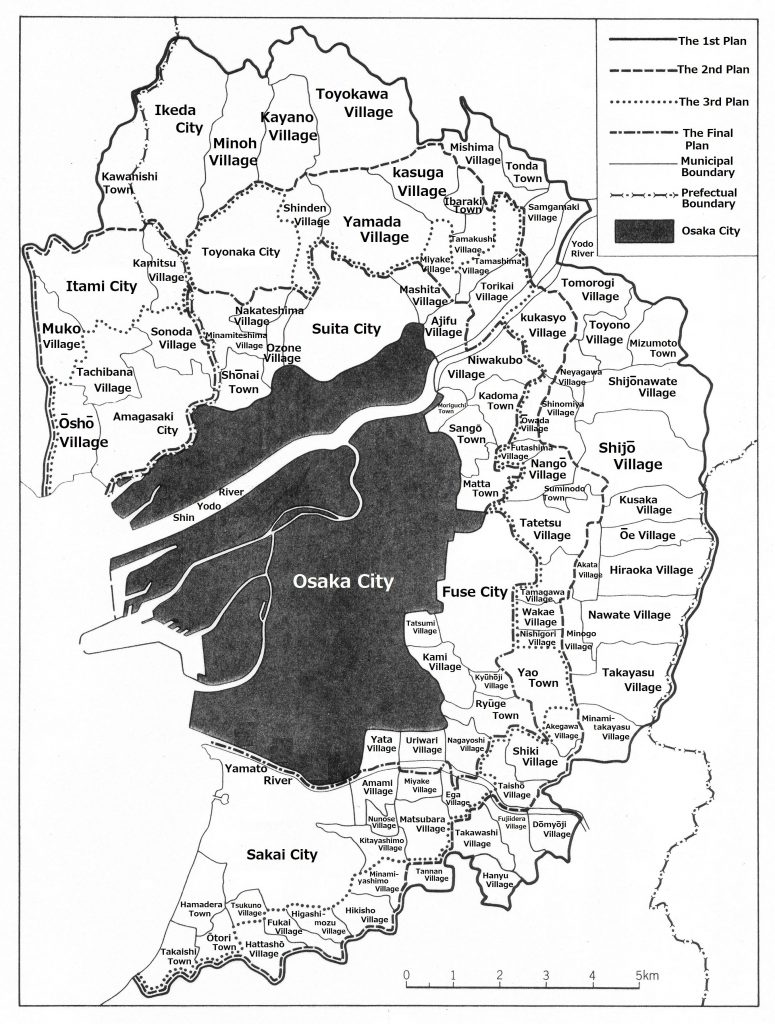

Thus the problems that accompanied population growth remained unresolved, and intensified during the war. Accordingly, as total war with China began in 1937 and dragged on into 1939, Osaka started to look to amalgamations as a means of addressing urban issues. Absorbing surrounding cities, towns, and villages would allow Osaka to conduct its urban planning more strategically over a wider area, while also strengthening the city against air raids by establishing open green belts on its periphery. The grandest plan, conceived over 1941-1942, would have incorporated not only cities in the immediate neighborhood of Osaka, such as Sakai, Toyonaka, and Fuse, but even Amagasaki and Itami in Hyogo Prefecture. Although in the end this was abandoned as the Pacific War intensified, the considerations that total war introduced to urban problems—namely, the idea of expanding Osaka to achieve more efficient governance—went on to become part of the genealogy of contemporary arguments for a larger administrative territory.

Mass Mobilization and the Citizens of Osaka

How did life change for the people of Osaka in the lead-up to, and during, the war?

Already in 1928, fully three years before the Manchurian Incident, an “Osaka Air Defense Exercise” had been held. This was the first ever such exercise in Japan to involve not only the military, but officials and citizens as well. Additionally, the Women’s Association for National Defense (Kokubō fujinkai) was founded in Osaka in 1932, the year following the Incident. It had grown up from the activities that the housewives of Ichioka (in Minato Ward) had voluntarily organized to send off soldiers who were out from the Port of Osaka, hosting them for tea and the like. In its grassroots origins and vigorous organizing, the Association was characteristically Osakan, but it also went on to help mobilize the population for war, roping in women and other citizens through various militaristic activities.

Furthermore, in 1938, following the outbreak of total war with China in 1937, Osaka City Hall mandated that “neighborhood associations” (chōkai) be set up in every such area of the city (the chō or chōme). Known as chōnaikai in other cities, the “three thousand neighborhood associations of Osaka City” (Ōsaka-shi sanzen chōkai) were formal organizations of residents established at the level of the self-governing Edo-period chō blocks. From the Meiji period on, these old chō neighborhoods became obsolete as units of state administration, which instead operated through partitions like school districts (composed from about ten Edo-period chō) and, above that, the administrative wards and their ward offices, which functioned essentially as branches of City Hall. However, the wartime neighborhood associations were established as a means of getting residents to cooperate with mobilization strategies, such as supporting the families that deployed soldiers had to leave behind, encouraging saving, collecting metals for donation, and so on. From 1940, the associations also served as the basic units of the system for rationing food and other necessities of daily life. Thus the citizens of Osaka were placed under mutual surveillance and mobilized for war on the basis of neighborhood-level residents’ groups, with the neighborhood association and its sub-groupings of direct neighbors (tonarigumi) organizing air raid defense drills and other related activities.

But these drills proved of little use in the face of American aerial bombardment. From March through August of 1945, eight mass air raids of over one hundred B29 bombers at a time devastated Osaka’s urban areas, burning most of the city’s core to the ground. And so, Osaka, once the biggest city in Japan, would have to rise from the ashes of the postwar.

2. Postwar to Present

Let’s make a quick overview of the course Osaka took from the postwar to the contemporary period.

Osaka’s Postwar Recovery

Once it recovered from the war, Osaka once again became the Kansai region’s biggest city, but its population never again reached its wartime peak. In many cases, this was because the people who had left Osaka, whether evacuated or bombed out, settled in the areas outside the city where they had ended up. Additionally, we could point to the fact that city experienced no large-scale expansions after the war, with only six small townships and villages being amalgamated in 1955. As Tokyo grew ever more dominant with the high-speed growth that began in the mid-1950s, Osaka became mired in a long period of “economic subsidence” (keizai no jibanchinka).

In the immediate postwar, there were arguments that Osaka, rather than following Tokyo’s example of emphasizing heavy and chemical industries, should aim to become a sleek city characterized by precision industries and the advanced education and culture necessary to support them. Such visions soon fell by the wayside, however, as Osaka opted to chase after Tokyo, reclaiming land along its coast to attract heavy industry.

This path did bring a particular kind of development to the city, in the form of new urban infrastructure, epitomized in the construction of the subway and highway networks that accompanied the 1970 Osaka Expo. But at the same time, as symbolized by the poisoned Nishiyodo River area, it also gave birth to multifarious urban problems such as serious air, water, and soil pollution.

Economic “Subsidence” and Arguments for a Bigger City

With the hue and cry about the city’s economic “subsidence”, Osaka business circles called repeatedly, from the early stages of the postwar boom, for the construction of an economic counterweight to Tokyo by creating more efficient, larger-scale governmental units in Kansai and thereby concentrating investment.

This is what constitutes the historical background of the current schemes for a new “Kansai Province” (Kansai-shū), which have been advanced alongside the calls for Osaka to be designated a metropolis (Ōsaka-to kōsō). If we look back even further for the origins of these visions, we would have to point to the wartime plans for massive amalgamations, which I mentioned earlier, and to the Regional Residencies-General (Chihō tōkanfu), supra-prefectural governments established towards the end of the war. Of course, the circumstances that necessitated larger sub-national governments were different in each case; what’s envisioned in plans for a “Kansai Province”, namely, economic revitalization through the concentration of investment in the Osaka Bay area, is of course not the same thing as the authoritarian and efficient administration demanded by a system mobilized for total war. Nevertheless, it should be clear to you that this vision of concentrating investment and resources in a larger economic bloc has been conceived not on the basis of ordinary residents’ interests, but overwhelmingly on those of corporations and their doctrines of efficiency.

With regard to plans for an Osaka Metropolis, the question of how to decide the sub-metropolitan units of residents’ self-government has become an important point of contention. Looking at the city’s history since the Meiji period, the units of local government have only ever gotten bigger, from neighborhood to school districts and, above them, to the city’s wards. But the fact remains that expanding administrative units has led to the hollowing out of local government by diluting that sense of actually having a say in managing one’s own affairs. In this connection, there are at present proposals to reevaluate the city’s wards as administrative units, to strengthen them as levels of self-government by granting them independent fiscal authority. However, if such special wards are to truly revitalize self-government by local residents in a way that respects each area’s historical circumstances and individuality, the decisive question will be whether they have the appropriate size and, concomitantly, the functional intimacy to sustain it.

3. Reflecting on the Course as a Whole

As we have seen in today’s class, contemporary debates about Osaka’s economic revitalization and self-government have deep connections to the courses the city charted before, during, and after World War II.

Whatever path the city will take, we cannot discuss the future of Osaka without reference to each locality’s individuality and the characteristics that have, over their long histories, cumulatively come to define their residents’ lives.

In the sixteen lectures of this course, we have presented the history of Osaka, from earliest times to the present, as the story of the formation of the city and of the various people who lived there. It is our hope that this course proves of some use in thinking about the picture that a multitude of people, locals and otherwise, will paint of the future of Osaka—a city of the world, sustained by its connections thereto, that takes in people and cultures from around the globe; yet also a city of places, whose residents, in living, working, and learning with love for their particular histories and cultures, transform localities in neighborhoods, and so sustain the urban fabric.