Introduction

As the title of this series indicates, we will be exploring the world of social groups revealed in the historical documents (komonjo) left to us by the people of early modern Japan. Our guide, Dr. Watanabe Sachiko, will present an accessible introduction to the reading of Edo-period sources using the Yoshino Goun monjo, an archival collection held by the Japanese history division in the Department of Literature at Osaka City University.

The analysis proceeds methodically through the deciphering of the original handwritten documents, unpacking their dense style into “spoken” form (yomikudashi), and preparing a modern Japanese translation. The aim is to reconstruct the web of socio-economic relations constituted by the Yoshino Goun, a house of apothecary (gōyakuya), specifically their distribution and sales structures and the field of social groups tied into them.

As such, this series provides a concrete introduction to the agenda and methods early modern Japanese urban social history, which aims to bring to light, in fine detail, the world of these social groups. We very much hope that the series will find wide readership among those with an interest in the history of the Edo period and its rich legacy of komonjo.

The Yoshino Goun Documents(Part 1)

In Japan, an unusually great number and variety of historical documents (komonjo) from the early modern period (1603-1868) have been preserved. They are replete with information that enables us to learn about the society of the time. While the deciphering and interpretation of the characters on their pages must of course take center stage in advancing such research, we can also glean valuable information by including extra-textual considerations in our analysis.

Over the course of this series, we will provide a concrete introduction to the methods of interpreting and analyzing early modern komonjo. To be sure, one can approach these documents from various angles; there is not necessarily a single right answer that lets us say, absolutely, “from document X we know Y.” Sometimes, after all, new interpretations reveal themselves when we come back to one komonjo with what we have learned later from another. Please bear in mind, then, that what is presented here is but one example of an attempt at analysis, albeit from real, ongoing research.

The documents we will be using come from an incompletely catalogued collection known as the “Yoshino Goun monjo” (YGM hereafter) held by the Japanese history division of the Department of Literature at Osaka City University (OCU). Yoshino Goun refers to a house of apothecarists (gōyakuya) in Osaka’s Unagidani district, whose business consisted in compounding and selling medicines as pills or powders. The significant capital and power of this merchant house, which secured its markets by setting up an extensive network of toritsugi (consignment retailers) all over Japan, has been described in prior research (See: Matsusaku Hisahiyo, “Kinsei chūkōki ni okeru gōyaku ryūtsū— shōnin ryūtsū no ichirei to shite,” Machikaneyama ronsō shigaku-hen 29 [1995]).

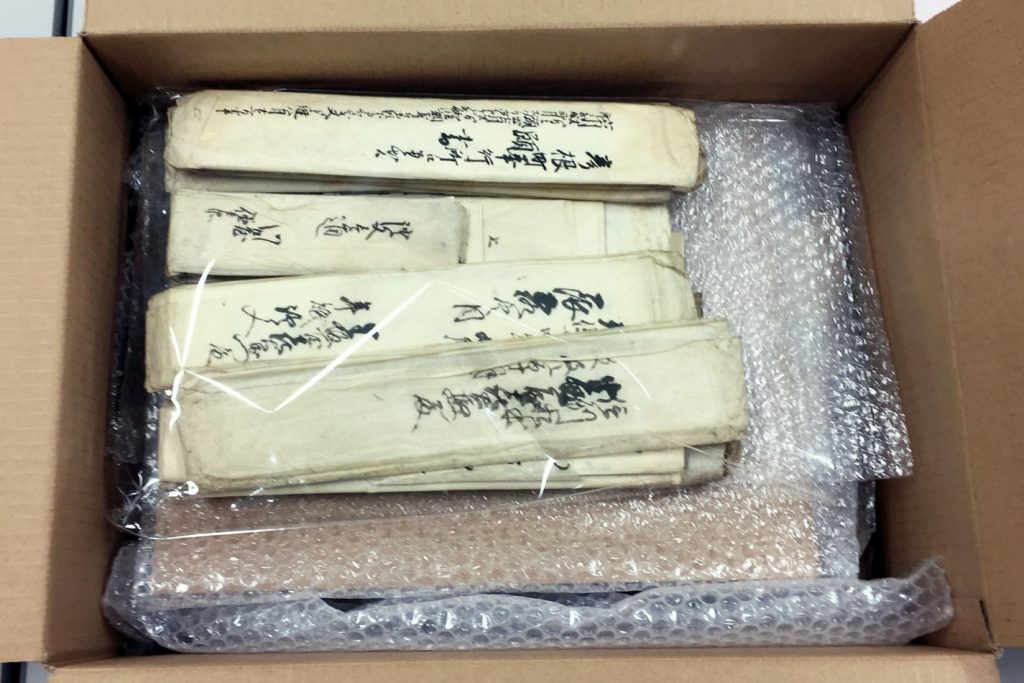

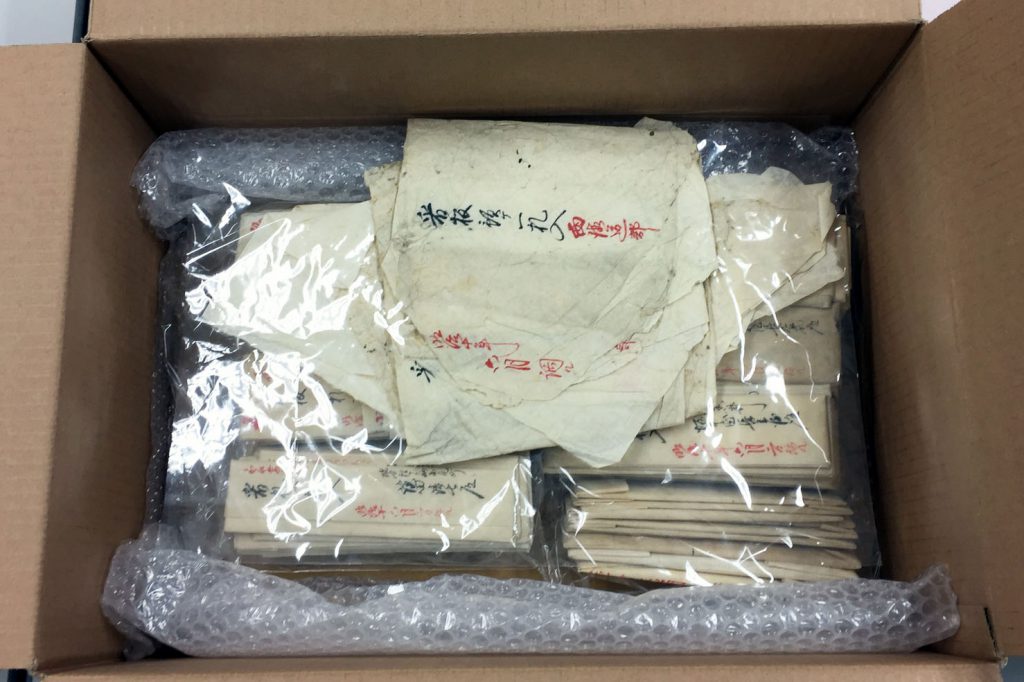

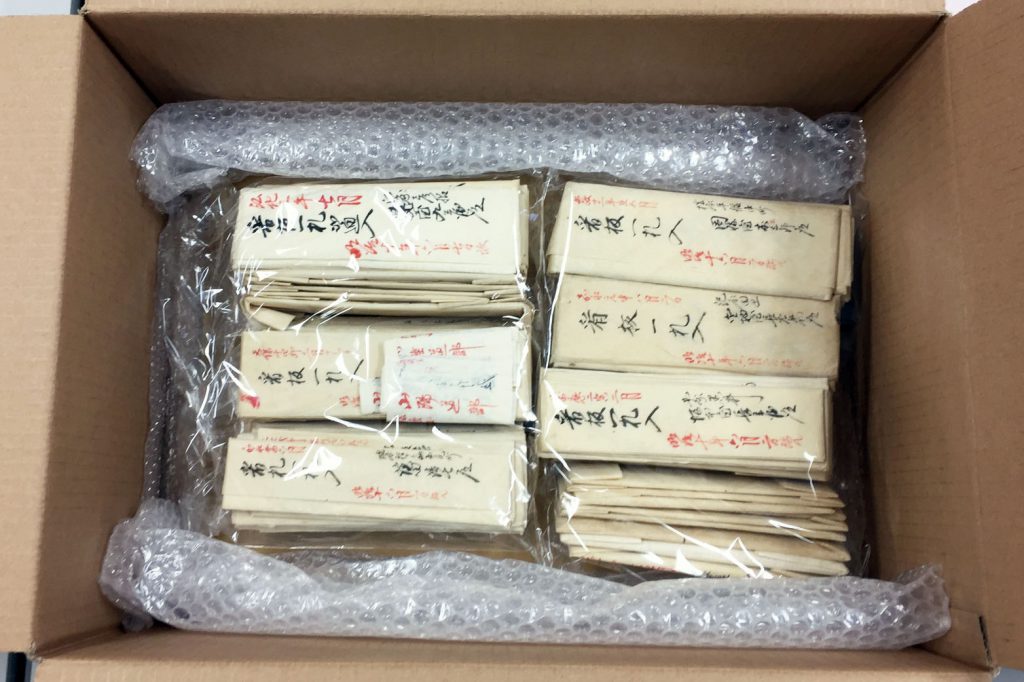

The YGM were purchased by the university from an old books dealer in March 2016. They came in a single cardboard box, divided among four plastic bags stacked on top of each other (bag 1 on top, bag 2 in the middle, and bags 3 and 4 together at the bottom).

To prepare komonjo for analysis, we first have to organize them by assigning each a number. There are various methodologies and theories of cataloguing such sources, but at OCU, in order to preserve them as they were found, we do not begin by categorizing them by subject; instead, as a rule, we proceed in the order they appear, from the top down, inserting each document into acid-free paper envelopes to prevent degradation. On the face of each envelope is recorded the identification number, the document’s title and date, author and addressee, etc. Of course we often find ourselves wanting to delve into their contents right away, but we hold off until later so as to avoid interruptions to the process, reading only the minimum required to establish the nature of the komonjo. We then record the information on the envelopes in a paper or electronic ledger to construct a catalogue. Once every last document is in an envelope and added to the catalogue list, the organizing process is complete.

With that, we can finally begin examining the documents. But where to start when there are so many? If a collection’s contents are too disparate to offer any clues we might well begin from the top of the pile, but in most cases there is a logic to the original groupings komonjo are preserved in. The question of where to begin reading—and of the nature of the collection as a whole—becomes much easier to answer when one can identify groups of similar documents, whether by author and addressee, subject, etc. With that in mind, let us take a look at the YGM catalogue to see if we can determine the character of the collection. I cannot replicate the whole catalogue here, but the most salient features are as follows:

- 356 documents in total

- Almost all written legal instruments (shōmon) addressed to Yoshino Goun house; senders are diverse and cover quite a wide geographic spread

- First layer in the box (Photo 1): mostly contracts with the house; contents vary, but many have to do with financial issues, e.g., setting up some kind of annual installment plan in cases where payment could not be made; 95 documents in total (original paper envelopes and the one or more contracts they contain [62 such bundles in all] each get their own catalogue number)

- Second layer (Photo 2): 7 envelopes, which likely originally held the third layer documents

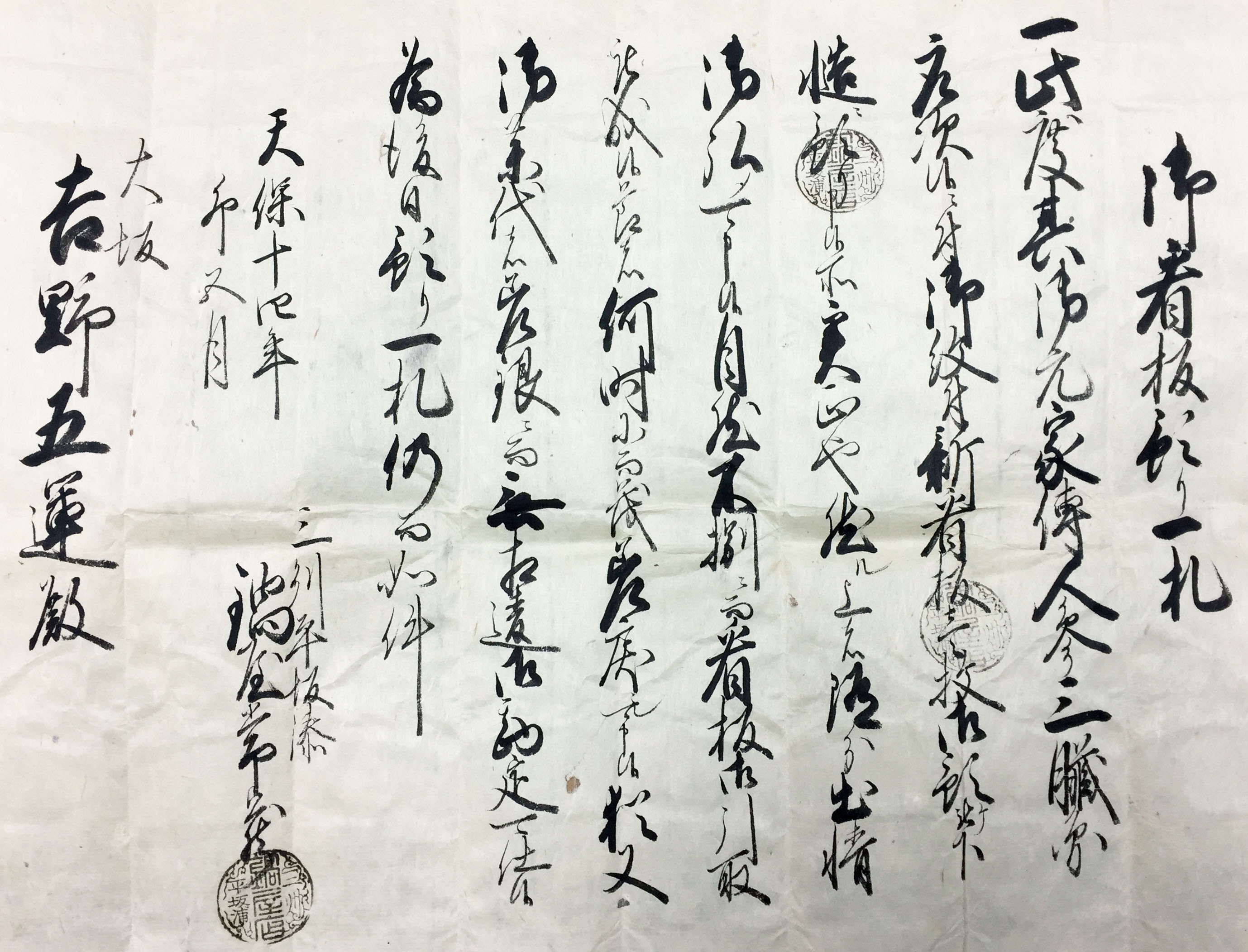

- Third layer (Photo 3): instruments submitted to the Yoshino Goun (almost all under the title kanban issatsu, or “placard bills”) with nearly identical formatting and promising, in having taken a proprietary medicine placard into keeping from the house, to work diligently to sell a ginseng medicine called ninjin sanzōen; 254 individual items (in 108 original envelopes)

The presence of multiple documents in a single envelope of course reflects some intention on the part of the original collator. By contrast, considering the collection was acquired through an old books dealer, it is much less likely that the division of documents in the third layer into plastic bags can tell us anything about their state at the time they were written. While we must bear this in mind, we can still use that division to help us understand the nature of the collection as a whole: all the documents have to do with Yoshino Goun business, but those in the first layer are quite different in nature from those in the second and third. And so, because the third layer items appear to have such similar formatting, we will begin by confirming just what these documents are that have been preserved together in such great numbers.

In the next installment, therefore, we will do a close reading of a sample document from the third layer followed by an analysis of its contents.