Hero Image:『写真で見る大阪市100年』、大阪都市協会

(Osaka City 100 years in picture, Osaka City Association)

Introduction

Hello, it’s Saga Ashita again from OCU.

In today’s class we’ll take up the period when, after becoming a megacity of a million people at the beginning of the twentieth century, Osaka got even bigger due to Japan’s economic boom (as a supplier to the Allies during World War I) and the accompanying influx of new residents to the city. Of course, this intensified urban social problems: as housing shortages grew worse and privation spread among workers, Osaka City, spurred by the outbreak of the 1918 Rice Riots, adopted and implemented new urban policies.

So today we’ll be looking at the specific characteristics of urban social problems during the age of “Big-time Osaka” (Dai-Ōsaka) and the policy responses to them. Let’s consider their historical significance by looking at concrete points of contact between urban policy and the city’s residents, namely, improvement campaigns that targeted specific districts.

1. The Intensification of Urban Social Problems and the Rice Riots: Population Growth and Deprivation

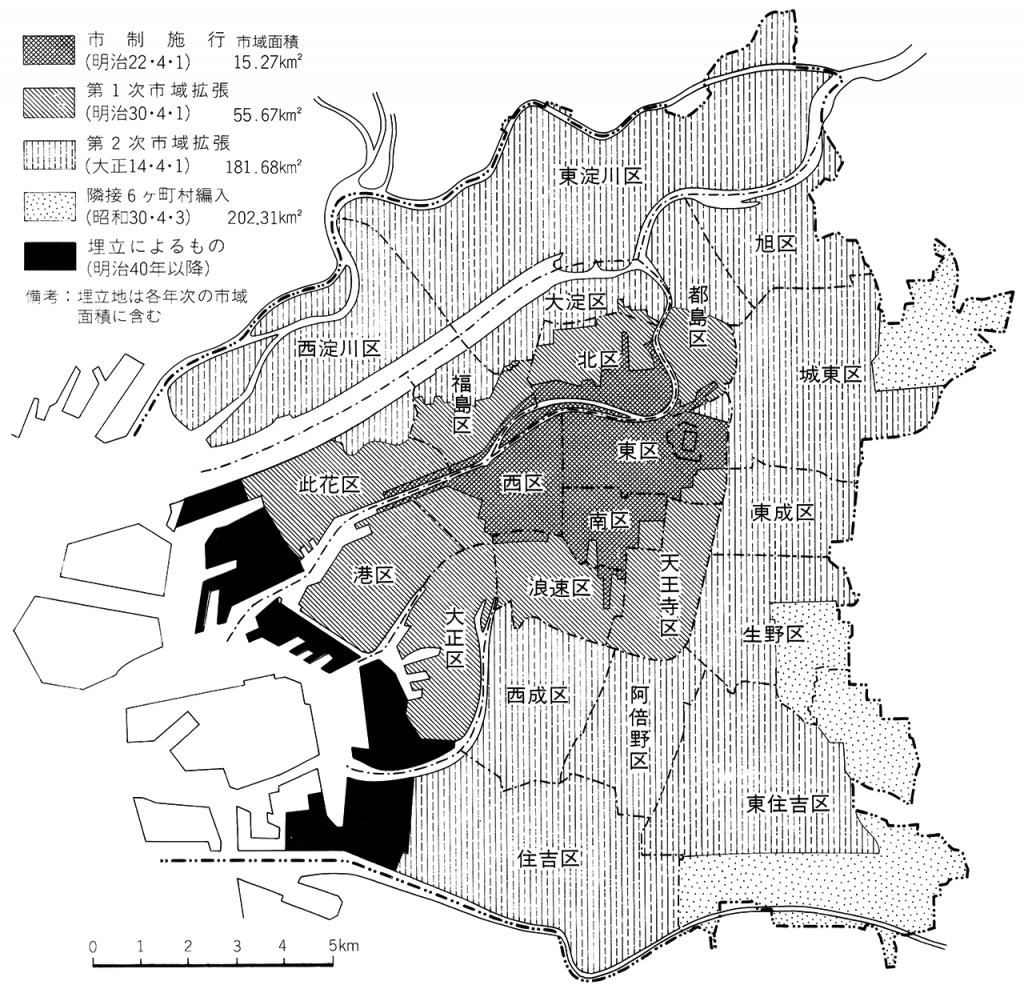

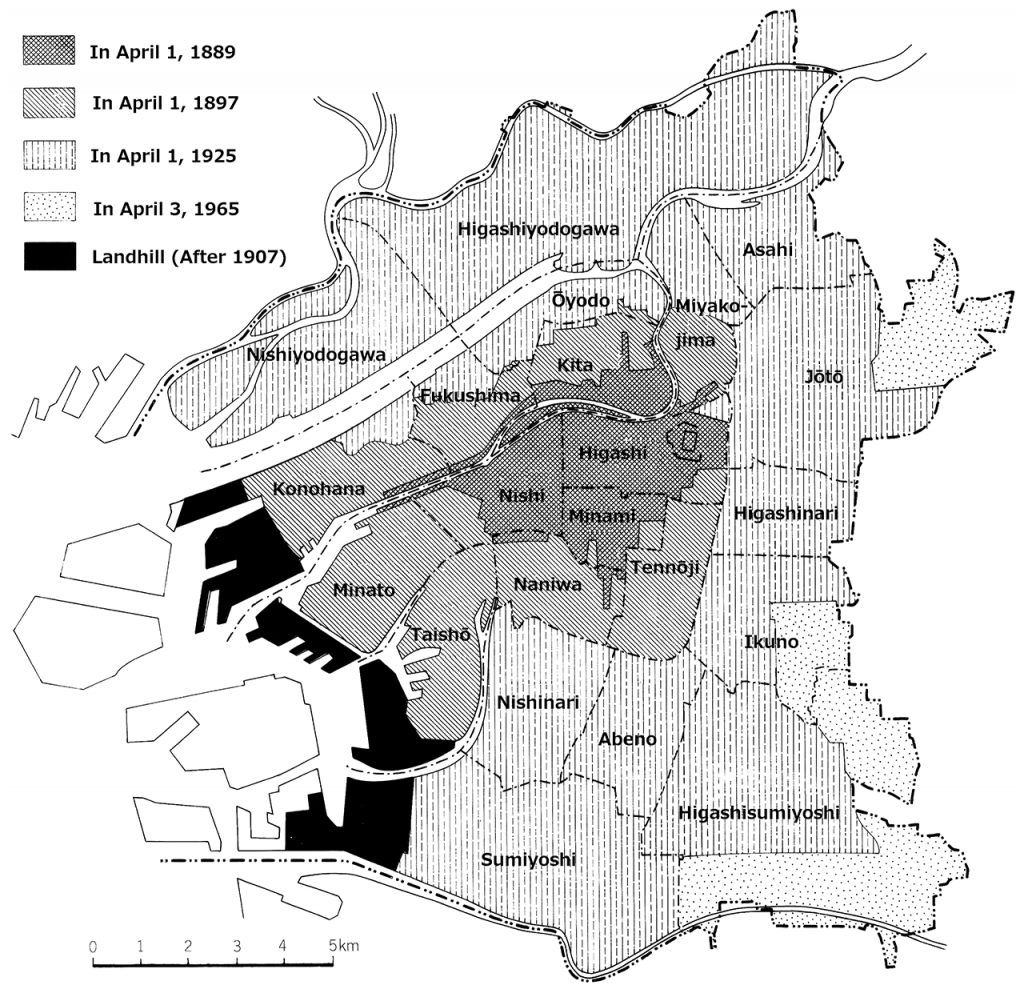

The period from 1914-1919, spanning World War I and the Treaty of Versailles, saw Japan’s economy to grow by leaps and bounds. The progress of industrialization fueled large increases in both the concentration of population in, and the physical expansion of, urban areas.

Let’s take another look at population trends in Osaka and its environs. Higashinari and Nishinari counties, which surrounded Osaka, experienced rapid growth in the 1910s: from 1914-1919 the rate of increase was an astounding 44% in the former and 50% in the latter. Half again as many people in only five years! This was of course due to the influx of factories and workers to the city’s periphery, and with the rapidly spreading urban sprawl, housing shortages became a pressing social problem.

| Jurisdiction | 1914 | 1919 | Percentage Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osaka City | 1,423,057 | 1,583,650 | +11.3 |

| Higashinari County |

140,039 | 201,101 | +43.6 |

| Nishinari County |

166,009 | 249,637 | +50.4 |

| Total | 1,729,105 | 2,034,388 | +17.7 |

Made by Ashita Saga

The chronic housing shortage in this period had two implications: first, it caused rents to rise steeply, leading to widespread indebtedness. According to estimates made by Osaka’s Social Affairs Office, in 1920 the city lacked housing for fifty thousand households. And between 1921 and 1921, the average rent in the city doubled. What did these fifty thousand families do? They didn’t all become homeless; rather, as we discussed last lecture with the Hachijukken tenement in east Nipponbashi, they somehow managed to get by by “renting space” (magari) from other renters, meaning that often two or more households shared a single dwelling.

The second implication of the housing shortage was deteriorating living conditions and overcrowding caused by the crude construction of the tenements and haphazard manner of urban expansion. The government created a label for areas of the city where such problems were particularly acute: “substandard housing districts” (furyō jūtakuchiku).

In short, with the city’s rapid expansion, the social contradictions of privation intensified for urban residents.

The Outbreak of the Rice Riots

With the prosperity of the war years, people flocked to the metropolis’s industrial periphery. The formation and expansion of slums kept pace, a typical example being Kamagasaki, with its concentration of single male day laborers. The population of Imamiya-cho district, which included Kamagasaki, was 11,200 in 1913; it had doubled to 23,500 by 1916, and again to 49,000 by 1920. What was more, compounding the general inflation driven by the war boom, the price of rice rose higher and higher as the rapid outflow of population from the countryside to the cities caused agricultural production to stagnate.

In August of 1918, the national government decided to deploy troops as part of the Siberian Intervention, an attempt by Western powers to forestall the Russian Revolution triggered by WWI. In Japan, this move led to widespread speculative buying and withholding of rice from the market, causing the price to jump to unprecedented levels. In Osaka, the normal price of 20 sen per shō (1.8 liters) reached 30 sen in July, 40 sen by the beginning of August, and a staggering 56 sen by the twelfth of that same month.

Spurred on as news made it out of Toyama Prefecture about the “housewife’s insurrection” (nyōbō ikki) that had broken out in local fishing villages, mass movements initially centered in western Japan spread throughout the country. They demanded price reductions (renbai) and general relief. In Osaka, price reduction riots broke out on August 11 around Tennoji Park and Imamiya-cho. The next day, troops from the Army’s 4th Division (based in Osaka) were mobilized to suppress the riots, but they continued until August 16.

The Rice Riots were an explosion caused by the accumulation of the various problems of social deprivation that had accumulated over the war period. They lit the fuse of the diverse social movements that followed, whether labor and debtors’ movements, the Buraku Liberation Movement, or, in the agricultural villages around the cities, movements led by tenant farmers who realized just how unfavorable tenancy looked in light of the expansion of the urban labor market. All the various class-based movements for democracy and social restructuring that flowered in this period had part of their origins in the social contradictions of the city.

2. The Birth and Development of Urban Policy

It was during this period that Seki Hajime emerged as a pivotal force in Osaka’s politics.

In discussing urban policy, we must first note the progress made in urban planning during the 1910s and 1920s. In 1917 the city established the Survey and Planning Committee for Urban Improvement, as well as the Ward Reform Office (Shikukaiseibu). The committee was Osaka’s first real deliberative body for drafting urban planning proposals, and it was headed up by Seki. The Ward Reform Office, which later became the Urban Planning Office, was to be responsible for implementing the plans put forward by the Committee. Over 1917 and 1918, Seki started a movement to push for the establishment of urban planning regulations, mobilizing even Osaka’s representatives to the Imperial Diet to help with lobbying. At the time, regulations pertaining to urban planning in Japan were limited to the “Tokyo Ward Reform By-Laws.” Osaka City, presenting an independent draft of an “Osaka Urban Improvement Law,” made a request to the central government for the implementation of proper national urban planning regulations. Seki had led the draft’s production, and it was chock-full of the latest Western policies, including construction controls that would be applied even outside city limits, use of expropriation (eminent domain) to reorder residential areas, and funding urban planning through property taxes tied to land value (with special taxes assessed in cases where public infrastructure investment drove prices up). These proposals had a definitive influence on the national Urban Planning Law and City Buildings Law that were promulgated in 1919.

Seki described his political philosophy as “social betterment-ism.” He argued for taking advantage of the benefits of capitalism, subjecting it to appropriate controls rather than allowing it the completely free hand of laissez faire. Exploitation by capitalists and class antagonisms between them and workers were to be moderated through national and municipal social policies. When it came to Osaka, he thought of urban planning and housing policy as two sides of the same coin and made realizing a “livable city” (or “city of amenities”; sumigokochi-yoi toshi) the most important task of municipal policy. (Seki was actually the first to use the word sumigokochi in Japanese as a translation for “amenity.”) In other words, Seki’s position was to raise standards of living for workers and other urban residents in order to mollify class antagonisms and promote the development of industry and culture in cities. He envisioned a more gradual process of capitalist revolution, holding that workers’ rights (beginning with unionization) should be recognized, but he was also against radical labor movements and socialism.

On the basis of this philosophy, Seki poured his energies into the development of municipal policies. He established the Osaka City Social Affairs Office in 1920 and, in the years that followed, oversaw the construction and management of many and various social institutions. These included municipal public housing (for sale and rent), hostels, unemployment offices, public baths, daycares, citizens’ centers, and more. In short, Seki Hajime’s municipal governance was a proactive response to the privation and other social problems faced by the city’s inhabitants.

3. Substandard Housing Districts: Reforms and Local Residents

In 1927, with the passing of the Substandard Housing Districts Improvement Law, the city of Osaka began reform efforts that targeted the Nipponbashi tenement areas we discussed last class. Formal designation of areas to be improved took place the following year, and all fell within the poor neighborhoods east and west of Nipponbashi. Ground was broken on the reformed housing in 1928, and construction of public housing, including three modern reinforced concrete apartment blocks, continued until 1943, finally stopping due to the war effort.

However, the residents of the back-alley tenements resisted the implementation of the reforms. Their reasons, as reported in the newspapers, were as follows: first, skimpy compensation for relocating; second, not wanting to live in Kamagasaki, the place usually designated as the destination for the displaced; and third, the prospect that the reforms would uproot them from the lives they had managed to establish for themselves. At first resistance focused on stopping evictions entirely, but eventually transitioned to movements for improving the conditions under which residents vacated their homes. Because their lives would, after all, be greatly improved by reformed residences, it might appear to us that resistance wasn’t called for. But we can also imagine that behind residents’ assertions lay, despite their poverty, genuine attachment to the lives they had eked out in the tenements.

Over the course of the reform efforts, there were multiple disputes between residents on the one hand, and, on the other, landlords, landowners like the Sumitomo family, or Osaka City Hall. At one point even a famous Osaka hoodlum/mafioso (kyōkaku) got involved as a mediator, but the disputes abated as landlords and landowners eventually made some concessions to tenement residents demanding compensation and the city government moved to improve the conditions of relocation.

The Osaka Social Affairs Office carried out detailed surveys of residents in the new municipal housing. These sources show clear improvements in conditions of life compared to what obtained in the age of tenements, most notably in the areas of health standards and education. Additionally, the phenomenon of multiple families living under one roof began to dissipate, bringing order to the tangled residential relationships that had once been the rule.

Informing City Hall’s designation of the Nipponbashi area as a target for reform was the conviction that there was a possibility of improvement. These advancements in urban policies were achieved not only through the offices of outstanding leaders like Seki Hajime, but also through the efforts of the everyday people who worked and lived in the metropolis that was Osaka.

Conclusion

Today we have discussed how Osaka developed proactive responses to the social problems that came with being a metropolis and were intensifying during the 1920s and 1930s. As you can see from the examples I gave of reform efforts, Osaka’s municipal policies achieved success in bettering residents’ lives, both tangibly and intangibly. Moreover, in their encounters with these policies, residents demonstrated their maturity as citizens. It could be said that the frictions between residents and policy responses to urban issues helped lead society towards the form it has taken today. The three modern apartment blocks I mentioned, known as the “Battleship Apartments” (Gunkan apaato), continued on as public housing after World War 2, home to tight-knit communities.

taken the photo by Asita Saga (July 2006)

Torn down and replaced with new buildings nearby in the early 2000s, today an old back-alley Jizō Buddha statue that stands in the precincts of the public housing around Nipponbashi is all that remains as testament to the lives lived by the common people of modern Osaka during the age of the tenements.