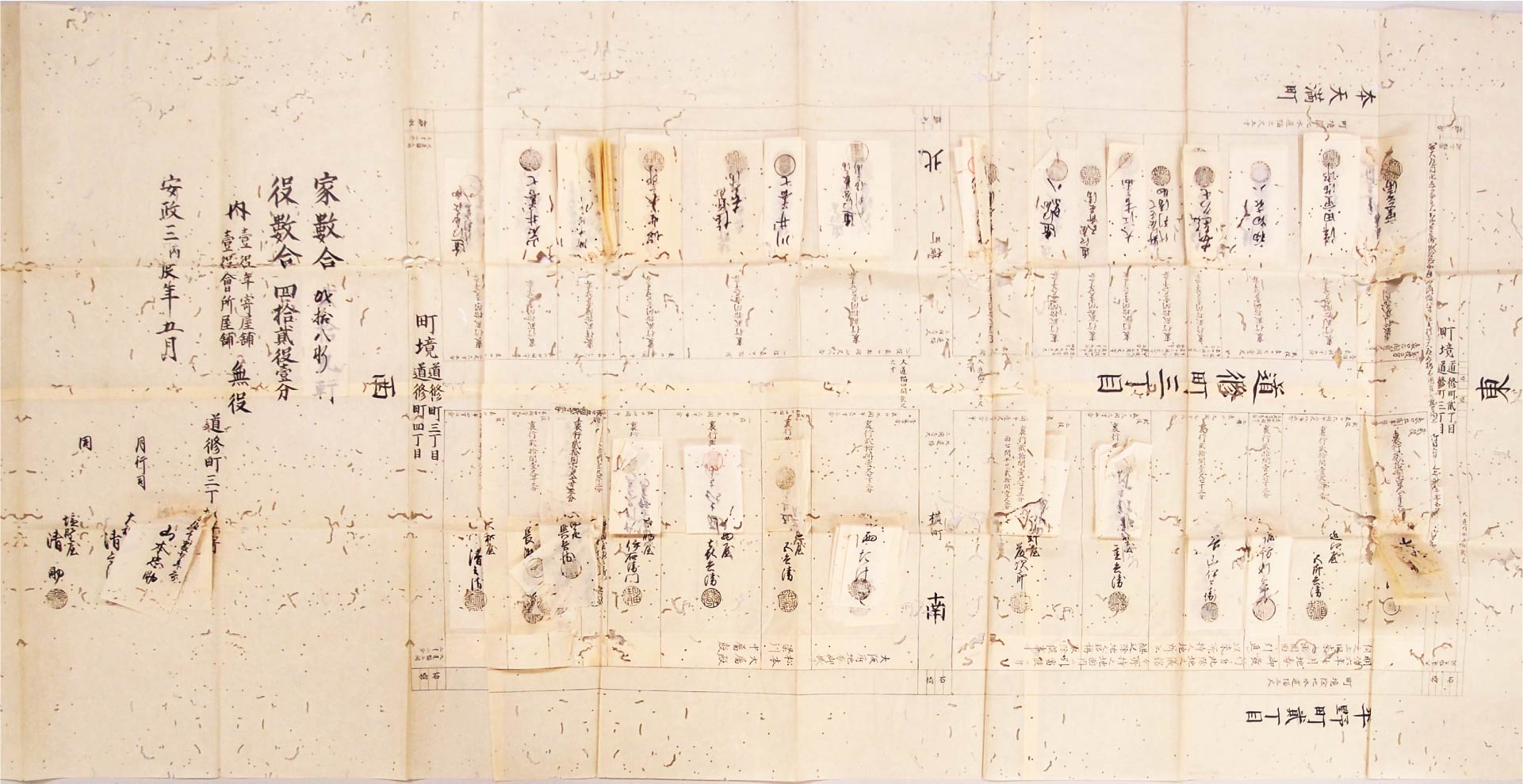

Hero Image: “The 1856 Doshōmachi 3-chōme Cadastral Map”

owned by the Osaka Municipal Library

道修町三丁目水帳絵図 安政3年5月 大阪市立中央図書館所蔵

The Cadastral Map shows land parcels and the names of owners of each parcel (ieyashiki) in the neighborhood. Every time an owner of each parcel changed due to inheritance, buying and selling, the name of new owner was written on a label stuck on the name of the previous owner.

水帳絵図は、町内の土地区画と、各区画(家屋敷)の所持者が示された絵図である。相続や売買で所持者が替わると、そのつど名前の上に貼紙を付けて訂正した。

Introduction

The chō, or urban neighborhood (association), was the basic unit of daily life in the early modern Japanese city. The character of the urban neighborhood varied widely from one city to the next. In the three megacities of Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto, chō were essentially communal associations of urban landowners known as iemochi. Landowners were not, however, the only residents of urban neighborhoods. Rather, neighborhoods had a diverse population, which included landowners’ family members, servants, and tenants. This session will examine the socio-spatial structure and administrative system of Osaka’s Doshōmachi 3-chōme neighborhood. Our analysis will focus particular attention on the internal documents produced by urban neighborhoods and the methods whereby they were managed.

1. What is a chō?

As I noted in lecture nine, during the mid-eighteenth century, there were 620 chō=urban neighborhoods or neighborhood associations in Osaka’s three commoner districts. The Edo-era chō is fundamentally different, however, from the contemporary chō. More than simply a geographic designation, the early modern chō was a communal association of urban landowners. Although other groups resided in urban neighborhoods, landowners were the chō‘s only formal constituents. As we will learn today, the neighborhood occupied an important position in urban society, serving as the basic unit of daily life for many urban denizens.

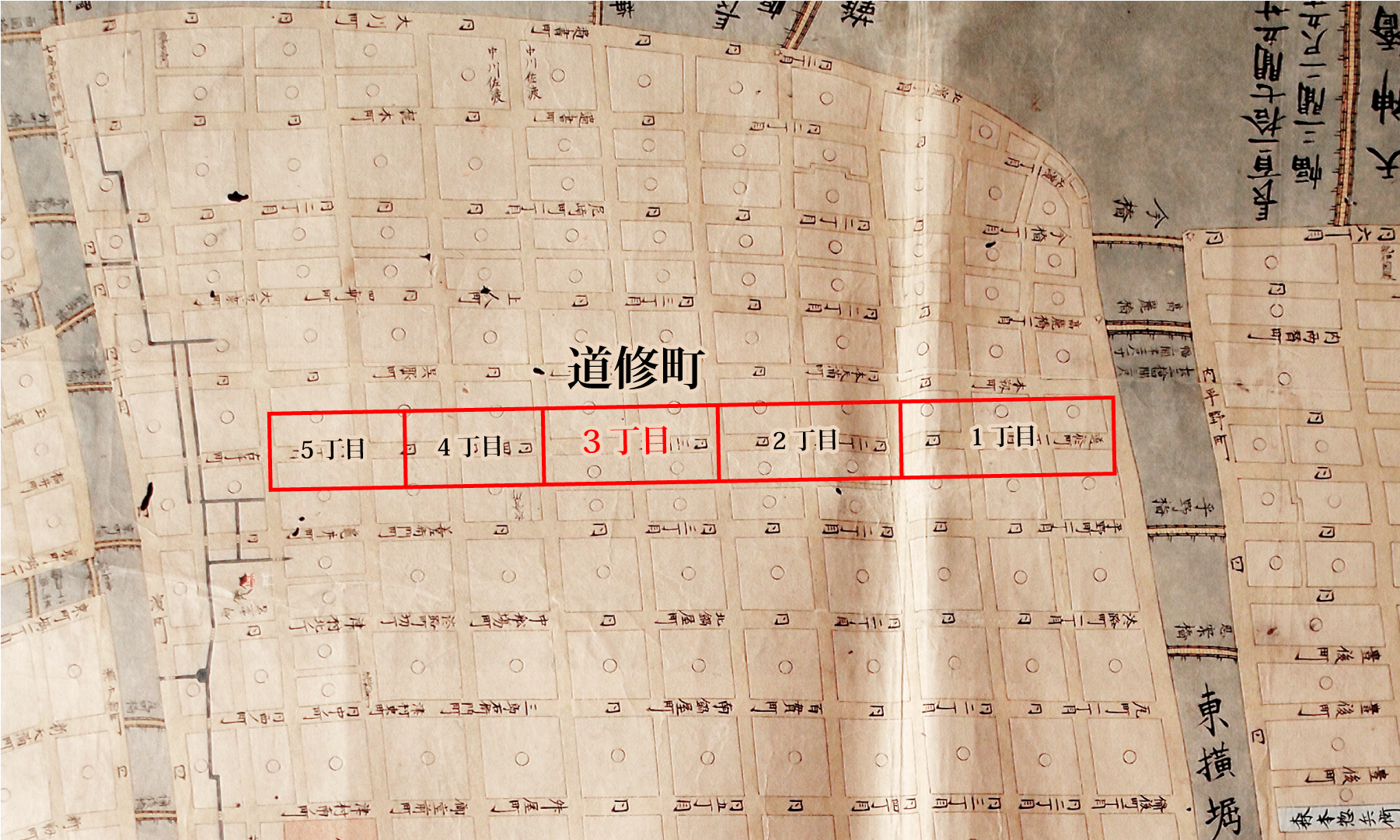

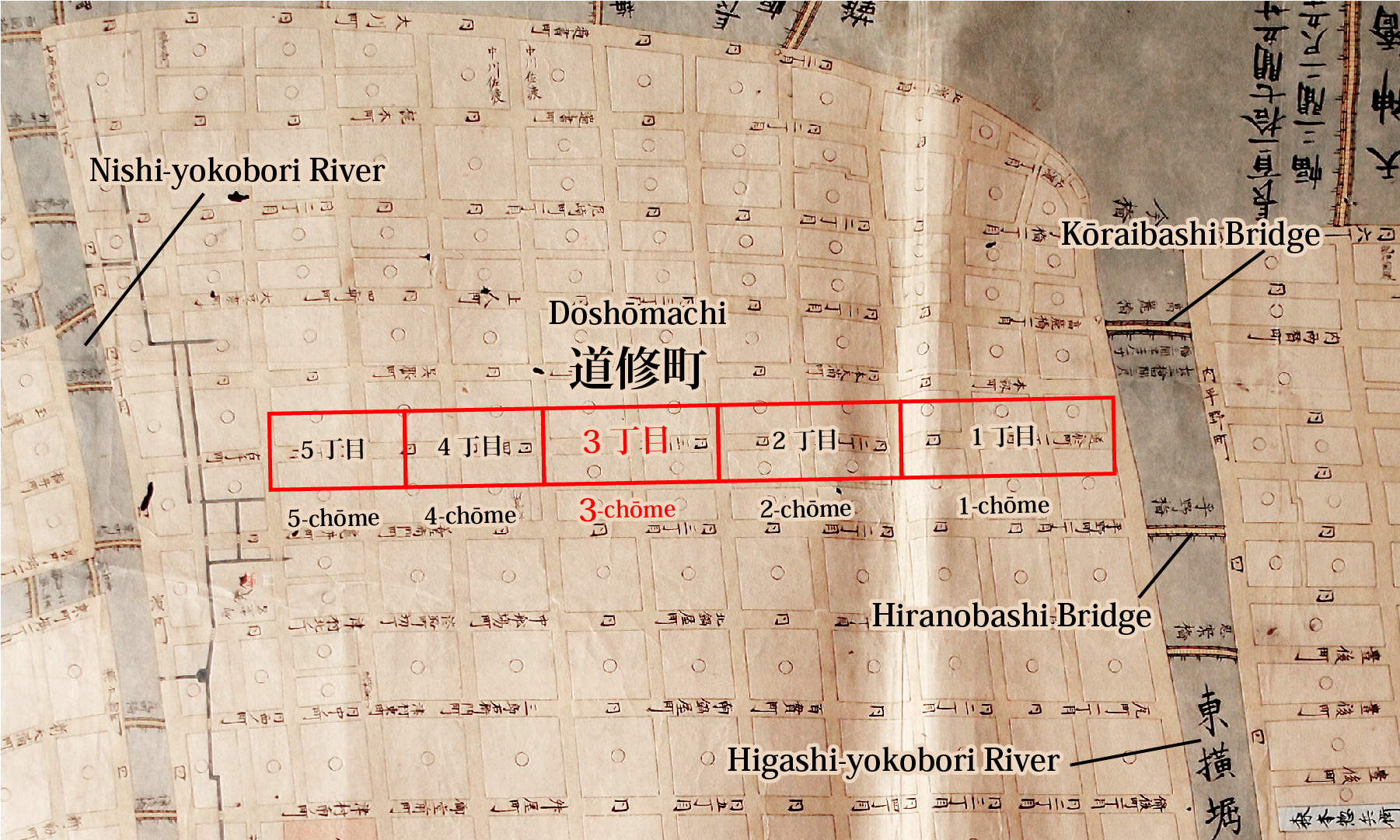

As we observed during session nine, the city’s commoner lands, in particular the Senba area, were arranged in a chess-like pattern with crisscrossing streets running north-south and east-west. Using a map from the 1830s, let us examine the internal composition on the Senba area.

owned by the Osaka Museum of History

As the map indicates, between the Kōraibashi and Hiranobashi Bridges, which span the Higashi-yokobori River, a major street named Doshōmachi Boulevard runs east-west through the Doshōmachi area towards the Nishi-yokobori River. The residential areas lining both sides of that street are partitioned into five chō or urban neighborhoods (Doshōmachi 1~5-chōme).

traced based on the document of the Osaka Municipal Library

(Reprinted from Tsukada Takashi, Osaka minsyū no kinseishi, Chikuma Shobō, 2017, p. 49)

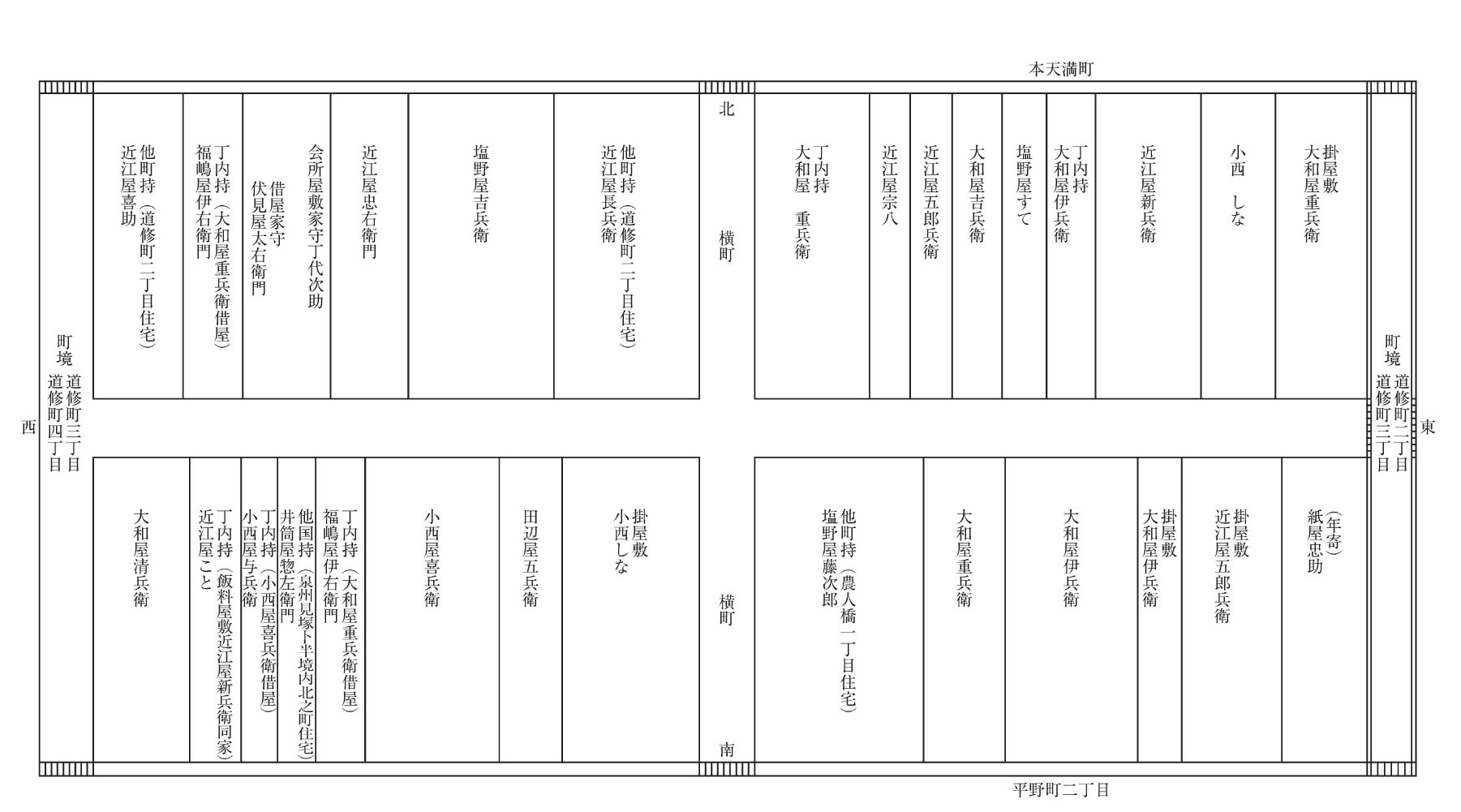

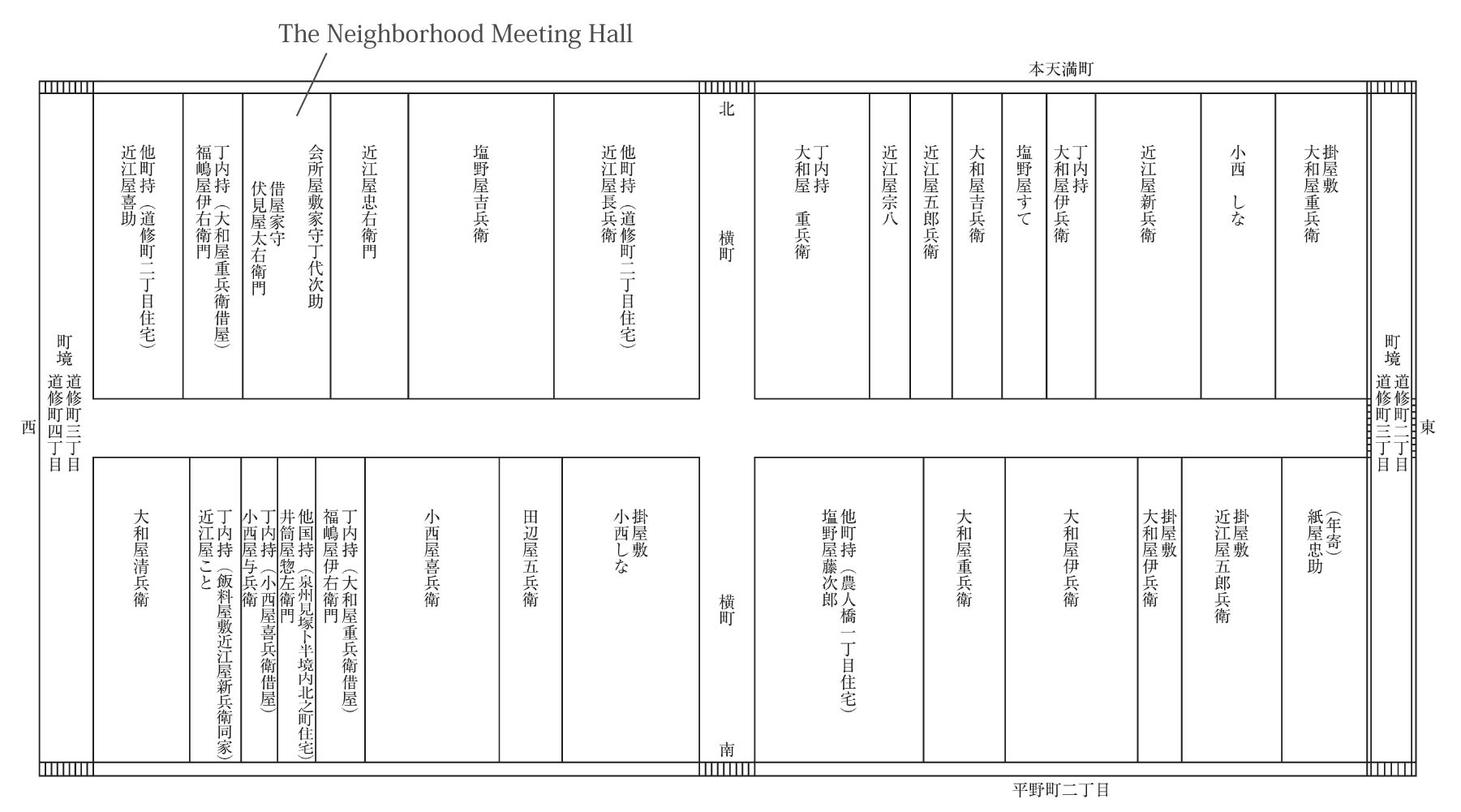

Let us examine the state of land ownership in Doshōmachi 3-chōme, using a cadastral register (mizuchō) from 1856. As you will immediately notice, the two blocks comprising Doshōmachi 3-chōme are partitioned into long, narrow residential tracts, which line a shared central street. Referred to as ieyashiki, these narrow parcels of land served as the basic unit of landownership within the urban neighborhood. Written on each parcel is the name of the individual who owned it. These landowners were the lone formal constituents of the neighborhoods in which they owned land. In other words, landowners were the only true members of the urban neighborhood association.

In Osaka, neighborhoods like Doshōmachi, which were located along an east-west thoroughfare, were commonly dual-sided, meaning that they were comprised of residential lots lining both sides of a shared street. In the Senba area, individual neighborhoods were commonly broken into two-block segments. In southwestern Osaka’s Horie area, however, individual neighborhoods were sometimes comprised of as few as one or as many as three residential blocks. In addition, there were some single-block neighborhoods which lined streets running north-south. Also in areas like Dōtonbori, which were located along rivers and canals, some chō were single-sided. Commonly, neighborhood associations held meetings during which their constituents discussed and addressed neighborhood issues. Accordingly, many neighborhoods maintained meeting halls on a plot of land within the neighborhood.

In the case of Doshōmachi 3-chōme, the third residential lot from the left on the neighborhood’s northern side served as the site of the neighborhood meeting hall. Urban neighborhoods also established their own internal regulations, including neighborhood by-laws and agreements. In addition, cadastral registers, which detailed local landownership rights, were composed on the neighborhood level. During the Edo period, ownership of a residential lot within a specific neighborhood community was, at its most basic level, a relationship of mutual recognition and protection binding local iemochi to one another. In addition, registers of sectarian affiliation and population records were produced annually within individual neighborhoods and submitted to the City Governor’s Office. Furthermore, copies of official proclamations issued by the Osaka City Governor were produced and maintained on the neighborhood level, as were official petitions and reports.

2. Chō Administration

An individual referred to as the neighborhood administrator (toshiyori) was the central figure in the system of chō administration. That administrator served as the representative of the neighborhood association’s constituents. In addition, the neighborhood administrator was commonly assisted by two secretaries who rotated every month. The cadastral register from the fifth month 1856 that we examined above bears the seals of neighborhood administrator Kamiya (Yamamoto) Chūsuke and neighborhood secretaries Yamatoya Seibē and Shionoya Seisuke.

In order deepen our understanding of chō administration, let us examine a neighborhood agreement from the intercalary eighth month of 1824 (owned by the Osaka Prefectural Nakanoshima Library). The document, which is sealed by neighborhood administrator Kamiya Chūsuke and 25 local landholders (including four on-site managers serving as proxy for absentee landholders), is a 37-article agreement detailing rules that constituents of the neighborhood are obligated to uphold. Importantly, the rules were established “on the basis of a consultation in which all of the neighborhood’s formal constituents participated.”

Let us examine the agreement’s thirteenth article. It states, “When meetings are held to discuss neighborhood issues, neighborhood constituents are required to attend unless they have a legitimate excuse.” The term neighborhood constituent refers here to the local landholders who have sealed the agreement. Importantly, tenants are not included in that category. As this suggests, landowners were the only formal constituents of neighborhood communities. This passage also indicates that the constituents of urban neighborhoods were obligated to attend meetings during which neighborhood-wide issues were discussed.

Let us turn now to article 26. It states, “Landowners living outside of the neighborhood must employ on-site managers to administer their properties. However, landowners residing in neighboring chō are exempt from this rule. In such instances, the landowner in question should consult with the neighborhood.” As this indicates, even when a landowner resided outside the neighborhood, they still maintained the rights and duties held by neighborhood constituents. In order to fulfill their obligations as members of the neighborhood association, absentee landholders were required to hire a proxy in the form of an on-site manager.

Article 25 of the agreement states, “Residential tracts may not be bought or sold at a price lower than appropriate for the area.” It is likely that this regulation was included in the agreement because of fears that below-market transactions would ultimately lead to a decline neighborhood property values. This article contains a proviso which I did not include. That proviso mandates that individuals buying or selling a property are first required to secure the consent of other neighborhood constituents in the form of their seal.

Lastly, let us examine article 15. It states, “When leasing a rental property, neighborhood constituents are required to report the tenant’s previous address and occupation to the neighborhood administrator and the other members of their five-household association, and thereby obtain the consent of the neighborhood association. Once they have done so, they must then obtain a document (ieuke issatsu) certifying the tenant’s identity. Only then can they formally lease the property.”

As this article indicates, in the case of Doshōmachi 3-chōme, landholders who wished to lease a rental property under their control were obligated to confirm the identity and occupation of the prospective tenant and obtain the consent of the neighborhood association as a whole. However, consent was obtained by filing a report to the neighborhood administrator and other members of one’s five-household association, rather than by obtaining the seal of other neighborhood constituents or submitting some sort a formal document.

The foregoing articles represent rules independently established by the constituents of Osaka’s Doshōmachi 3-chōme neighborhood. Such by-laws and agreements are not unique to Doshōmachi. In the early modern period, individual neighborhoods established their own rules and regulations. The fact that urban neighborhoods had such rules and regulations is an expression of the fact that they were highly-autonomous, internally stratified social organizations.

3. The Chō’s Socio-Spatial Structure

In early nineteenth-century Doshōmachi 3-chōme, there were more than 100 tenant households. At the time, the neighborhood had a resident population of over 600, including the families of landowners and tenants, and servants. Let us begin this section by examining the residential mode of Doshōmachi 3-chōme’s residents.

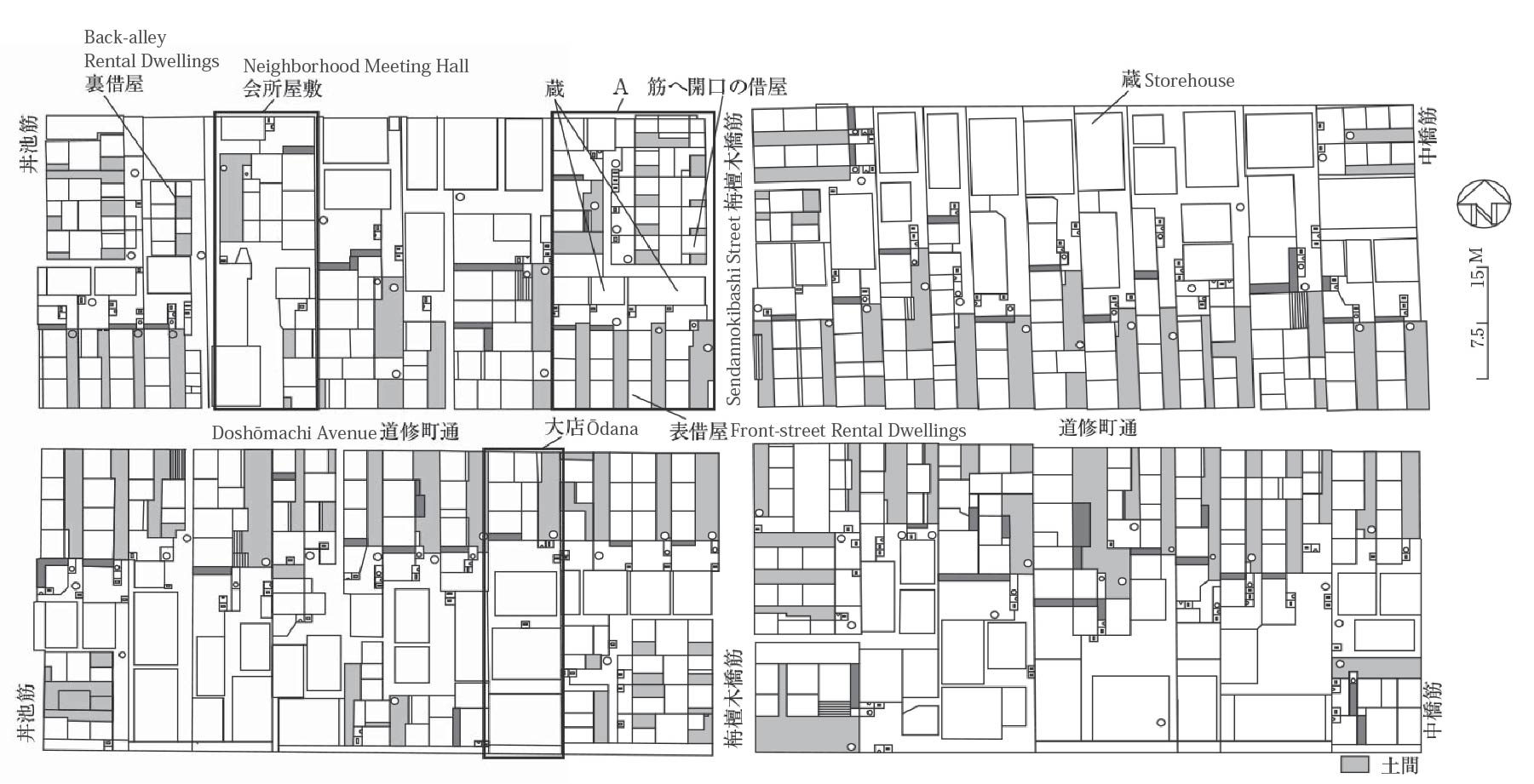

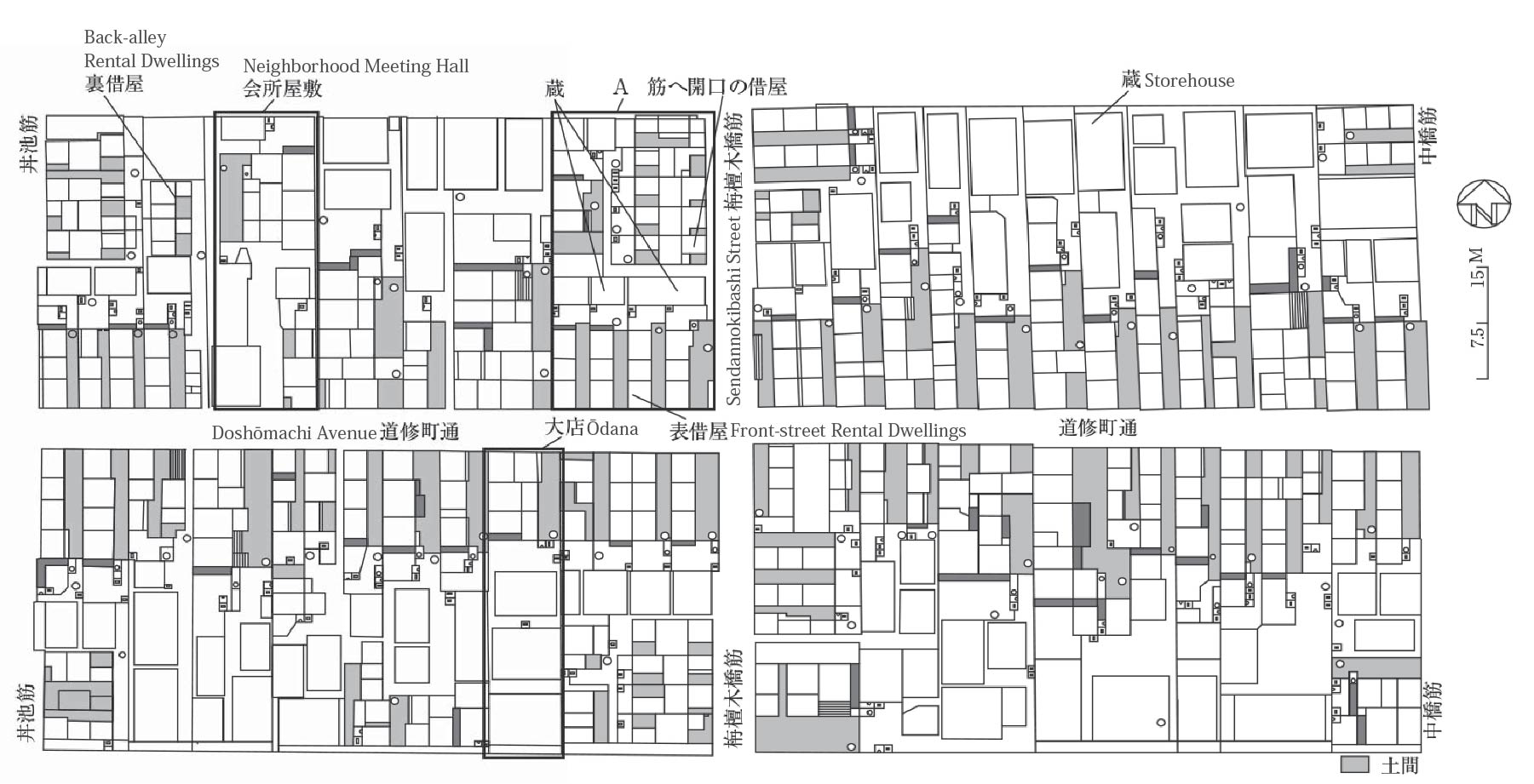

drawn based on Zusyū Nihon toshishi, University of Tokyo Press, 1993

(Reprinted from Tsukada Takashi, Osaka minsyū no kinseishi, Chikuma Shobō, 2017, p. 54)

This map shows the locations of dwellings and other buildings in the northern part of Doshōmachi 3-chōme during the early-Meiji period (Include a citation for the map in which its author, Professor Tani, is mentioned). Although this map is from a different period, if we compare it with the 1856 cadastral map examined, it is clear that the location of buildings corresponds almost perfectly with the locations of individual lots depicted in the cadastral map. As in the 1856 map, Doshōmachi 3-chōme’s blocks are comprised of long, narrow tracts of land with uniform lengths of 36.6 meters and frontages of between 5.5 and 18.2 meters.

The areas that are identified as ōdana, or large merchant houses, occupied and utilized entire residential tracts for their own purposes. As the Meiji-era map indicates, large merchants houses commonly maintained dwellings in the front and storehouses in the rear. In addition to living on the tract of land that they owned, such merchants also commonly maintained an on-site commercial space. In such cases, no rental dwellings were constructed on the property. The mesh-covered area of the dwelling shows the location of an unpaved passage leading to the rear of the residence. Here, the landowner resided with his family and a small number of servants.

Let us now focus our attention on the area lining Sendannokibashi Street labeled “front-street rental dwellings.” In the front section facing Doshōmachi Avenue, there are four three-room rental dwellings, each containing an unpaved passage. In the case of rental dwellings located along a front street, it was possible to open a shop and engage in on-site commerce. Long, narrow residential tracts included both front sections, which lined streets like Doshōmachi Avenue, and rear sections located along back alleys. In the case of both large merchant houses and front-street tenants, one’s place of residence also served as the site of one’s occupation. In contrast, because back-alley tenement dwellers did not live along a main street, they were unable to engage in revenue-generating commerce at their place of residence. In that sense, back-alley tenements served only as residential spaces rather than spaces that combined the functions of occupation and residence. In Doshōmachi 3-chōme, which was located in the central part of Senba, there were only a small number of back-alley tenements. However, if we take Osaka as a whole, there were many back-alley rental dwellings of the sort depicted in Edo-period dramas. For example, in Horie’s Miike-dōri 5-chōme neighborhood, there were a large number back-alley rental dwellings and tenements.

The area labeled “neighborhood meeting hall” served as the site of Doshōmachi 3-chōme’s aforementioned meeting hall. The tract of land on which the hall was located and the on-site buildings were the collective property of the neighborhood’s constituents. The structure in the rear is the site of the meeting hall, while the front section lining the street is the location of a block of rental dwellings. Neighborhood meetings were held at the meeting hall. In addition, it served as an office where paid neighborhood employees known as chōdai carried out duties related to the neighborhood’s administration. In Osaka’s urban neighborhoods, chōdai supervised various lower-ranking employees, including clerks, who assisted them with their duties, and night watchmen.

4. Summary

Article 37 of the aforementioned 1824 neighborhood agreement states, “Neighborhood records and the various tools and implements stored in the neighborhood meeting hall should be written down in a register and that register should be entrusted to the annual representative.” As this indicates, the various sorts of internal records that were produced in urban neighborhoods were stored in the neighborhood meeting hall. Registers containing a list of important neighborhood records, as well as tools and implements stored in the neighborhood meeting hall were produced and maintained on the neighborhood level. In addition, a system existed whereby these lists were placed in the care of an annual representative, who served as the neighborhood’s chief financial administrator for the year. Presently, Doshōmachi 3-chome’s records are held at the Osaka Prefectural Nakanoshima Library. In addition to the documents mentioned today, that collection of documents also contains registers of sectarian affiliation, ledgers containing copies of official proclamations, and documents related the quartering of arriving guard units. Those sorts of documents were preserved under the above system.

As the regulations contained in the neighborhood agreement examined above indicate, Osaka’s urban neighborhoods were self-governing communal organizations. They were administered on the basis of neighborhood by-laws and consultations in which all neighborhood constituents were obligated to participate. Those constituents shared ownership of the meeting hall and the land on which it was located. At the same time, various important neighborhood records were stored in the meeting hall. This itself is an expression of the unique character Edo-era society, which, unlike so many other premodern societies, bequeathed to future generations of vast body of written records, many of which were composed by ordinary people and preserved by the social organizations of which they part.