Hero Image: 『写真で見る大阪市100年』、大阪都市協会

(Osaka City 100 years in Pictures, Osaka City Association)

Introduction

Hello again. I’m Saga Ashita from Osaka City University.

In today’s class, we’re going to see how local people’s daily lives changed as Osaka developed into an industrial city with the steady advance of modernization and capitalism during the Meiji period. While industrialization made Osaka into a metropolis of a million people, disparities deepened and the masses faced lives of poverty. Let’s take a concrete look at actual living conditions during this period of industrialization, from the Meiji to Taisho periods, by “anatomizing” the structure of daily life and work in a block of tenements around Nipponbashi.

1. A City of a Million: The Industrialization of Osaka

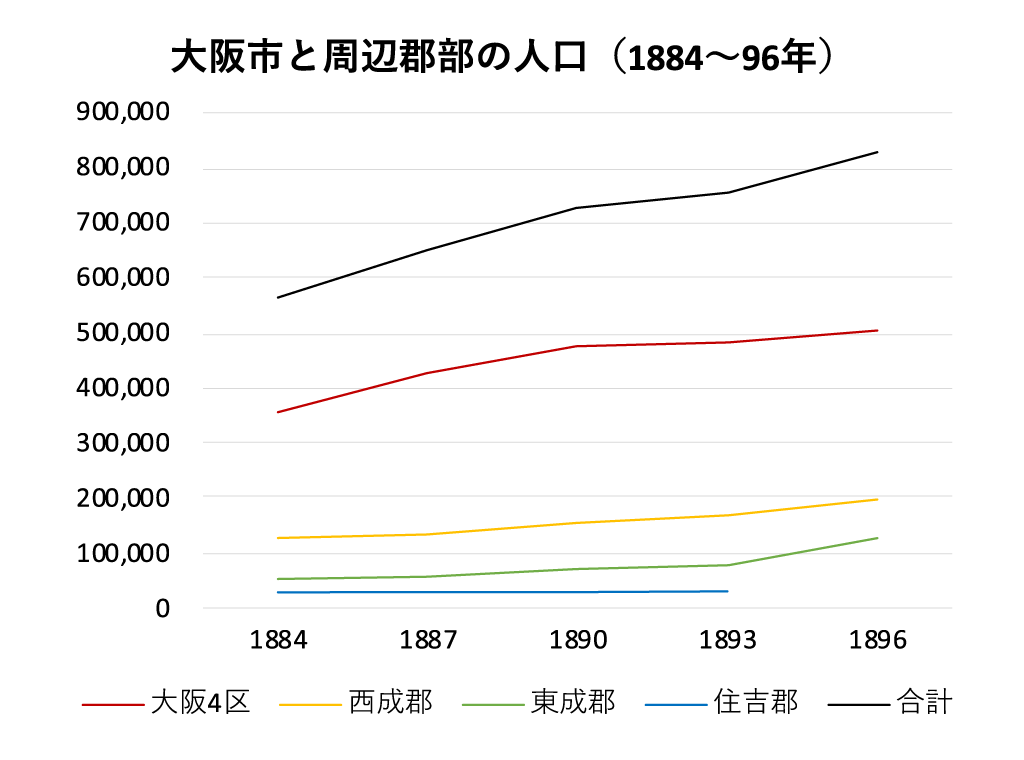

First let’s look at the population trends in urban Osaka during the Meiji period. It’s estimated that the city’s population peaked in the second half of the eighteenth century (i.e., mid-Edo period) at around 420,000 and declined thereafter, reaching about 280,000 by the first year of Meiji (1868). As I discussed in the last lecture, with the move of the national capital to Tokyo and the abolition of silver currency, Osaka’s economy slumped and the population remained stagnant even into the 1870s. However, migration to cities increased from the 1880s, when rural areas suffered a serious recession due to the government policy of fiscal austerity known as the Matsukata Deflation. This was also a time when new enterprises, in the form of modern joint-stock companies, proliferated in sectors like rail and textiles. Urban Osaka’s economy finally started to grow and, as a result, the population began to increase steadily.

In 1889, with the implementation of the new system of administrative divisions (shisei-chōsonsei), Osaka City was established as an entity encompassing the four “wards” (ku) that made up the urban area. The Osaka City of the time was much smaller than today—falling well within the circle drawn by Japan’s Rail’s current Osaka Loop Line—but it had a population of over 500,000 by 1896. Osaka’s population growth actually slowed slightly during the 1890s, which is likely explained by the fact that the central urban area was already saturated.

On the other hand, in Nishinari-gun and Higashinari-gun, the counties that surrounded the city, the population increased virtually without interruption from 1880 through the 1890s. Again, this was probably because rural migrants had nowhere to settle in the saturated central areas.

| Year | Osaka City | Nishinari County | Higashinari County | Sumiyoshi County | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884 | 355,844 | 127,198 | 52,698 | 28,486 | 564,226 |

| 1887 | 426,846 | 135,484 | 58,566 | 29,425 | 650,321 |

| 1890 | 476,392 | 154,353 | 69,312 | 29,875 | 729,932 |

| 1893 | 484,130 | 167,034 | 76,765 | 30,233 | 758,162 |

| 1896 | 504,285 | 197,170 | 126,937 | 828,392 | |

In other words, outward urbanization (i.e., the phenomenon of “sprawl”) began from the 1880s as new sites for factories and accompanying workers’ tenements were constructed on the outskirts of the urban nucleus.

In 1897, Osaka undertook its first revision of the city limits. This was prompted by de facto, accretionary expansion of the urban area, which proceeded variously through the inflow of population attracted to the growing crust of companies and factories constructed around the old city, as well as through continuous infrastructural development (beginning with the construction of a new port). As if to chase after the social and economic shadow the city cast beyond its actual administrative limits, the expansion was carried out to secure a bigger tax income and strengthen the city’s financial base. The city’s population jumped to 750,000 as a result of this first revision, and as industrialization sharply intensified during the beginning of the twentieth century, Osaka finally developed into a megacity of a million people.

To sum up, Osaka matured into a modern metropolis in terms of both size and structure due the advance of industrialization and urban development from 1880 through the early 1900s.

2. 1880s Tenement Districts

Now let’s start looking at the real conditions of life during the period of industrialization through the example of Nipponbashi. Broadly, we can say that it was over the second half of the nineteenth century, from the final years of the Edo period through late Meiji, that the “tenement districts” (nagamachi) of the city’s lower classes transformed into modern slums.

The tenement districts were parts of the city where, beginning in the Edo period, the many poor classes of day laborers had become concentrated. They dwelt in “wood-rent lodges” (kichinyado), cheap, bare-bones accommodations where the room fees were about the same price as some firewood (hence the name). Even after the Meiji Restoration these areas continued to be dominated by rows of these back-alley tenements. They were divided into single rooms for rent by the day (hibarai) and inhabited by day laborers and other members of the lower classes such as beggars.

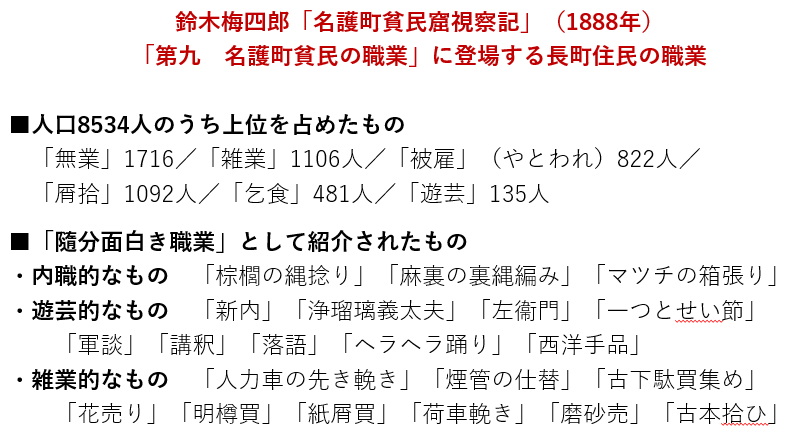

In 1887, a now famous piece of documentary journalism was serialized in the Jiji shinpō newspaper under the title “Observations of the Pauper Hovels of Nagomachi.”

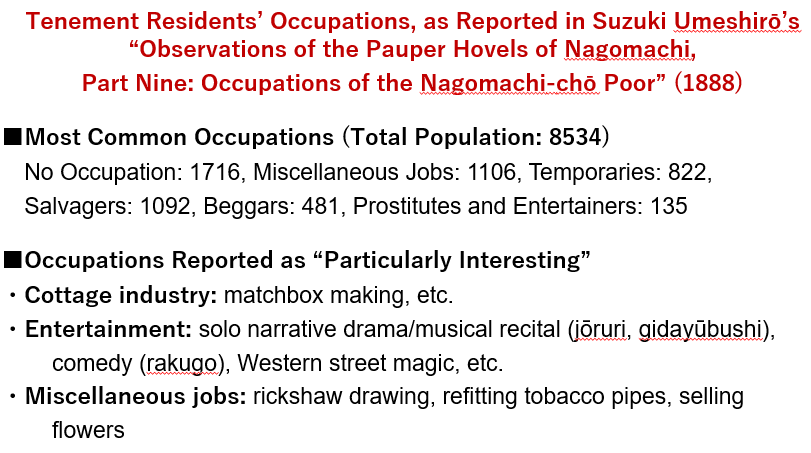

The author, a man named Suzuki Umeshirō, had taken it upon himself to investigate life in a tenement district. According to this mid-Meiji source, the occupations of the tenement classes could be broken down more or less as follows: 1) umbrella and fan makers, 2) day laborers like rickshaw men, etc., 3) salvagers and beggars, i.e., the very lowest classes, 4) various entertainers, 5) petty street vendors, and, finally, 6) modern industrial workers (in match factories, etc.). Notably, the lowest of the low (salvagers, etc.) made up a large proportion of the area’s inhabitants, but the number of industrial workers was on the rise. For at this time the umbrellas and other petty wares, along with new products from the factories proliferating around the tenement districts, made up part of Japan’s exports to China and Southeast Asia. The lower classes of Osaka were, therefore, swallowed up in the Asia-wide wave of industrialization and economic change.

Another important aspect of life in the tenement districts was how landlords and other rentiers had, since the Edo period, affixed themselves to the lower classes through daily room rentals, pawnshops, and moneylending. While they did provide the lower classes with lodging and introduce them to employers, there were also operators who not only extracted comparatively high rents, but lent money at usurious rates, rented bedding and mosquito nets, and sold crude meals and sundries.

With the progress of modernization, however, the financial burdens on the landlords increased. (For example, through the imposition of fees to run local schools.) What was more, severe cholera epidemics swept Osaka in the 1870s and 1880s, hitting the Nipponbashi area hard. Extracting rents from the lower classes therefore became less enormously profitable than it once had been, and there came calls, citing hygienic concerns, for the demolition or relocation of the slums where the poor were concentrated. As a result, various problems emerged around the issue of relocation, for instance in 1886, when the Osaka government tried to demolish the city’s slums and make the lower class residents relocate outside the urban area. The plan encountered resistance from the landowners of Namba village, the proposed destination for displaced residents, and wasn’t carried out as intended. In the end, though, a “slum clearance” was effected in 1891 through a large-scale demolition and reconstruction of the city’s back-alley tenements, which brought an end to the early modern structure of lower-class society and the daily rentals that had served as its nucleus. However, it turned out that driving people out of these areas simply served to scatter them to others such as the side streets east and west of Nipponbashi or southwest to Kamagasaki. As Osaka continued to grow, so would the slums.

From the 1890s, new tenements were built as small to mid-size petty manufacturing grew up in the side streets east and west of Nipponbashi Boulevard (Nipponbashi-suji, today Sakai-suji), producing a mixed residential-industrial townscape. On the other hand, in the southwest of the tenement district (Kamagasaki) a new type of “wood-rent lodge” was being constructed in large numbers: the ground floor rooms were occupied by the owners, while many men lived together in large rooms on the second. Spaces called yoseba were also set up, the largest one in Kamagasaki, where day laborers could gather to be selected for jobs, and so the area naturally became a slum made up of single males. This was what sowed the seeds of the post-World War II “Kamagasaki Troubles”, a series of riots fueled by the increased homelessness and crime that came with the hard economic times.

3. Taisho-Period “Substandard Housing Districts”: The Hachijukken Tenements

We can get a sense of life in the slums by looking at the Hachijukken nagaya, a block of tenements which lay just to the east of Nipponbashi Boulevard.

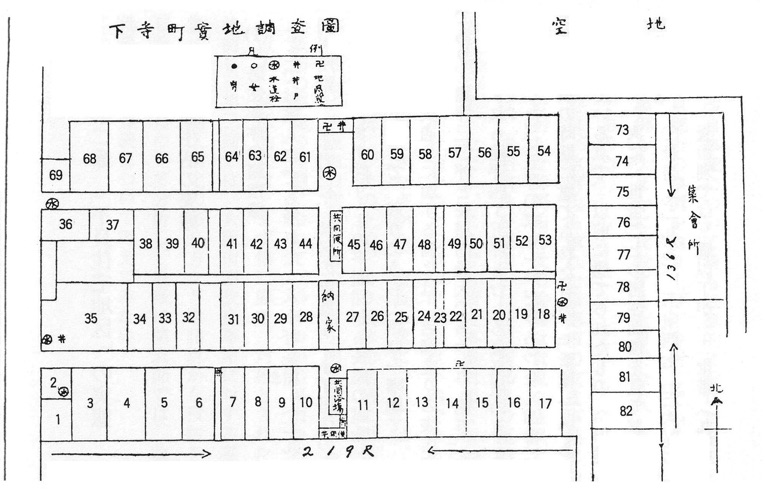

We have a good picture of life in these tenements, which were built in 1890, thanks to a detailed survey carried out by the Osaka City Social Affairs Office in 1924.

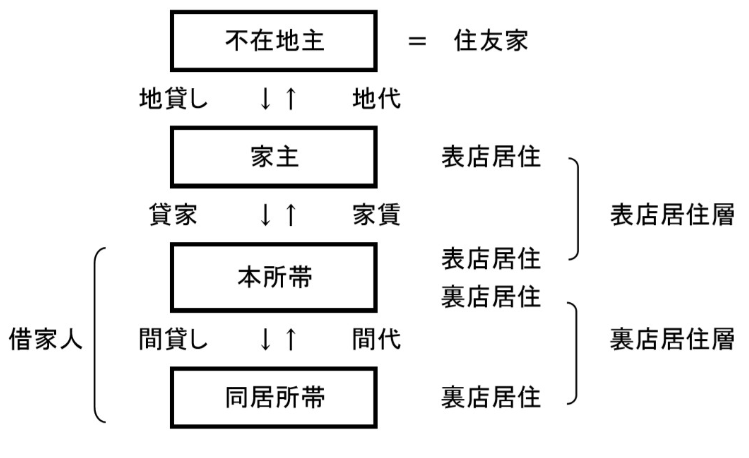

504 individuals in 129 households lived in the tenement block’s 79 rental units. With one “main household” (honshotai) per unit, the fifty left over lived as “lodger households” (dōkyo shotai), or subtenants of the main tenants, usually renting out (magari) a unit’s second floor (narrow two-story units were the norm in Osaka).

quoted from Ashita Saga, Kindai Ōsaka no Toshi Shakai Kōzō, Nihon Keizai Hyōronsya

(『近代大阪の都市社会構造』, The Structure of Modern Osaka’s Urban Society)

That is to say, most of the apartments in these tenements housed two families, and some as many as three.

About 40% of families in the block had only one room; in terms of area (i.e., regardless of how many rooms), more than 70% had less than 7.5 tatami mats of living space (13.6m2/147 sq. ft). Given that the average family size was approximately four, this was a very high density. With the exception of the block landlord’s household, the remaining 128 tenant families had to share three wells and one faucet with running water. The rental units comprising the block’s most recently built addition each had a toilet—hardly impressive if one knows that these 24 apartments were home to 46 families, but the lap of luxury compared to the tenements’ other 82 families (again excepting the landlord’s), who had to share just two toilets.

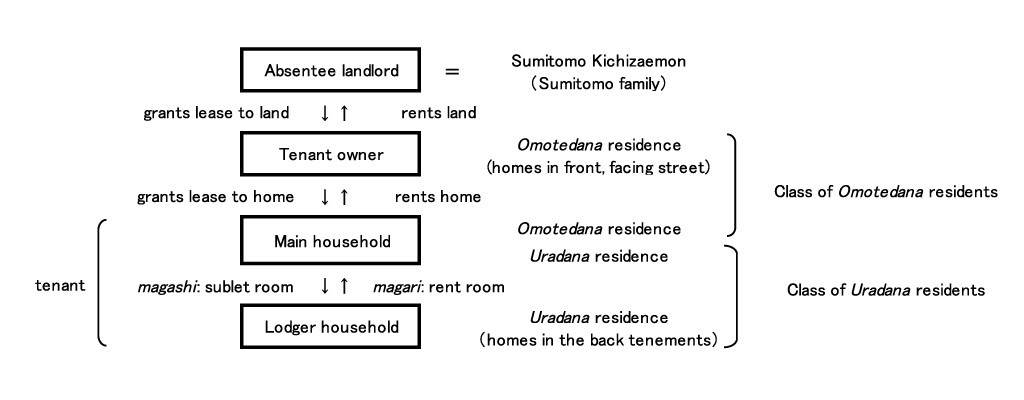

Next let’s look at class relationships in the Hachijukken tenements in terms of the land they stood on, the actual buildings, and the residents. The tenement block’s lot was owned by the famous Osaka financial conglomerate (zaibatsu) Sumitomo Kichizaemon. The tenements therefore had a multi-story class structure, with the Sumitomo family at the very top as absentee landlord/landowner; next, the tenant-owner/building landlord (yanushi), who leased the lot from Sumitomo to run his rental business; and finally the “main” and “lodger” households I mentioned before, with the “mains” leasing apartment units directly from the building owner and then renting out space to “lodgers”. The building owner had an income of several hundred yen per month, high for the time, and his personal apartments were large, with a private well and separate connection to the water main—clearly a class apart from his tenants with their monthly incomes of around fifty yen.

What about tenants’ occupations? Most household heads worked in salvage, a tradition that extended back to the Edo-period tenement district, but in many cases their children worked in local factories and some were even skilled laborers. In other words, we can see a trend across generations of people rising from the traditional poor classes of day laborers and salvagers to become modern industrial workers.

As I’ll discuss further in the next lecture, Hachijukken and the many other Nipponbashi-area tenement blocks like it became the objects of municipal efforts to improve “substandard housing districts.” This was because local conditions came to be seen as an expression of the problems of urban society, epitomized in poverty and disparity. But at the same time, it is plain that the residents of these areas were also viewed as sources of the labor power that modern industry could not do without.

Conclusion

What I’ve tried to show today is that, amidst the shadows of Osaka’s industrialization, there is the history of the common people who, crowded into tenement blocks on the urban periphery, supported day-to-day production in the metropolis. By peering where we can through the historical record, we can observe the traces left behind by these people who flowed into Osaka from the end of the nineteenth century, living resolutely in the face of social contradictions made manifest in growing wealth and productive power on the one hand, and deepening disparity and poverty on the other.