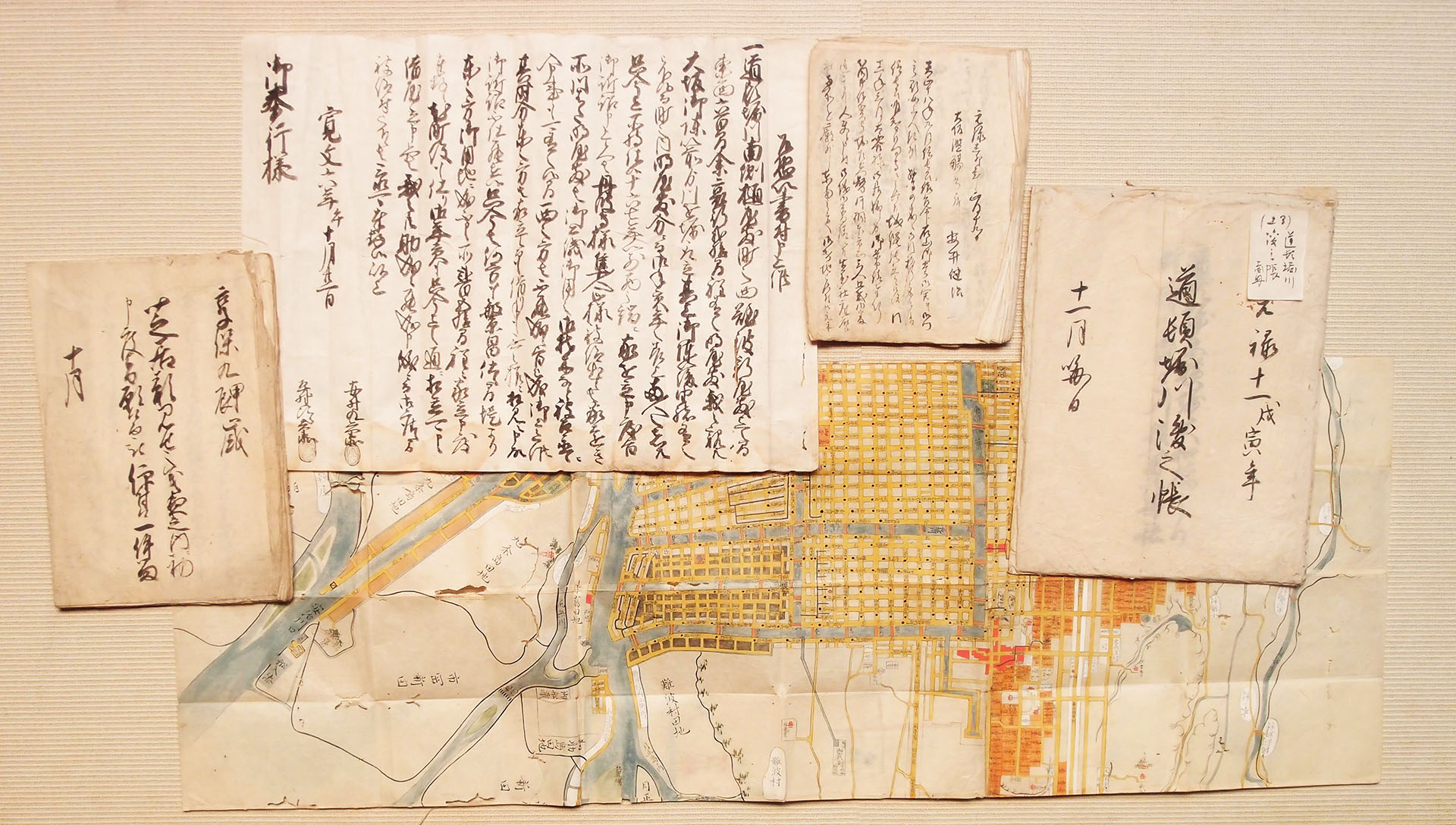

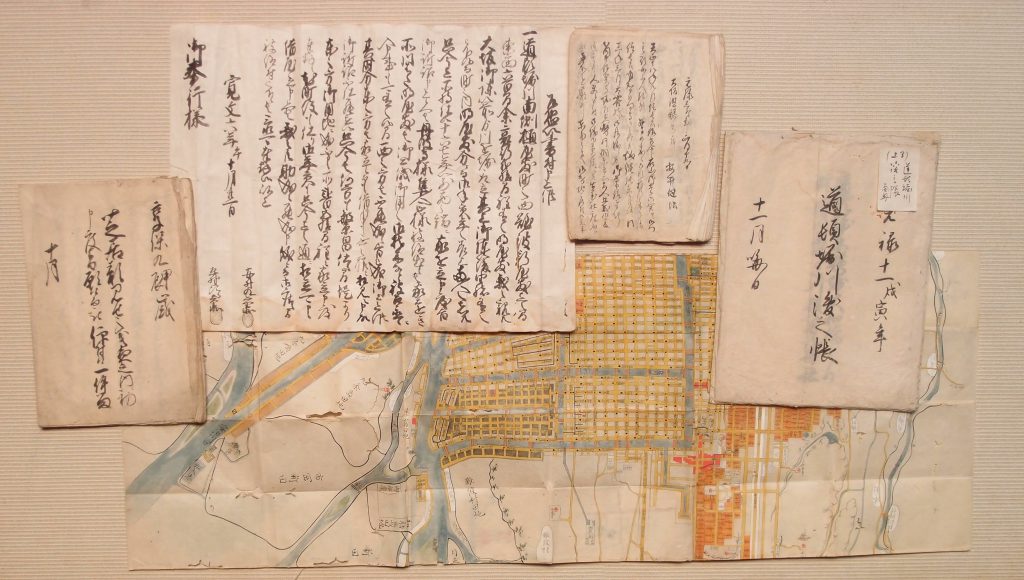

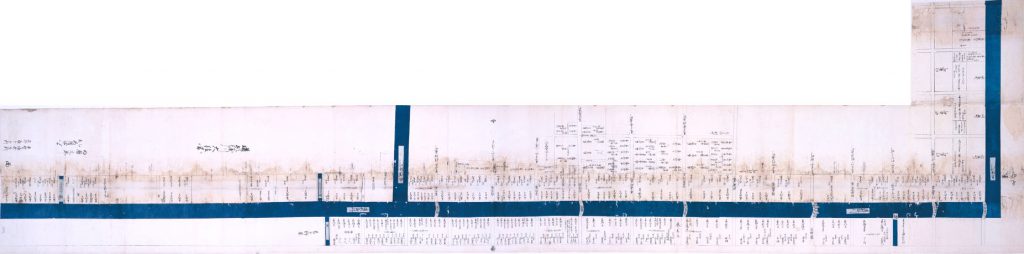

Hero Image: The Yasui House Documents

owned by Osaka Museum of History

安井家文書 大阪歴史博物館所蔵

Introduction

Even today, Dotonbori is one of Osaka’s best-known entertainment districts. Dōtonbori and the surrounding area were constructed in conjunction with the formation of the early modern city. During a court case held in the 1960s, the descendants of Yasui Kuhē, one of the individuals who directed Dōtonbori’s development, presented a body of documents which described the neighborhood’s formation and development. Those documents provide us a wealth of information about the making Dōtonbori. In addition, in recent years, a second collection of previously unknown Yasui House records was discovered in Shizuoka Prefecture. The Yasui House was one of the houses that served for successive generations as District Administrator of Osaka’s Minami District. During this week’s lecture, I will introduce the Yasui House records while analyzing Dōtonbori’s formation and early modern urban development.

1. Present-Day Dōtonbori and the Discovery of the Yasui House Documents

Currently, in the vicinity of Dōtonbori’s Ebisu Bridge, there is a riverfront promenade known as the Tonbori Riverwalk. From the promenade, one can observe the pleasure boats that carry tourists along the Dōtonbori Canal. The promenade was constructed in the twenty-first century as part of a broader redevelopment project carried out in the Dōtonbori area. This was not, however, the first time that the area was targeted for reconstruction. During the 1960s as well, a large-scale redevelopment project was executed in Dōtonbori. At that time, in an effort to improve quality of the water in Dōtonbori Canal and prevent storm surges, land on both sides of the river was gradually reclaimed and the river walls on both sides were raised. Half of the reclaimed land was sold off to land owners on both sides of the Canal. The money collected was then used to defray the construction costs. The remaining portion of the reclaimed land was designated as a greenbelt, although part of it actually served as the site of a paved walkway.

After the redevelopment project was announced, the descendants of Yasui Kuhē claimed rights to the land along Dōtonbori Canal and filed suit against the Osaka prefectural and city governments. The case took place over a period of approximately ten years and ultimately the judge rejected the claims of Yasui Kuhē’s descendants. During the trial, Kuhē’s descendants claimed that Kuhē and his co-developers used their own financial resources to construct Dōtonbori. Accordingly, they argued, Kuhē’s descendants were the rightful owners of the land lining the canal. In an effort to bolster their claim, they submitted, as evidence, a large volume of Yasui House records. Subsequently, those records came to be stored, together with a previously-donated collection of Yasui House documents, at the Osaka Municipal Museum (the precursor of the Osaka Museum of History). In 2012, a second body of Yasui House documents was newly discovered. They were preserved by Mr. Endō Ryōhei, a resident of Shizouka Prefecture’s Fukuroi-shi. The Endōs are relatives of the Yasui. Mr. Endō graciously entrusted these documents to the Osaka Museum of History, where they are presently stored. Before the documents were transferred, I visited Mr. Endō’s residence in Shizuoka Prefecture together with Yagi Shigeru, one of the Osaka Museum of History’s curators. I distinctly remember the excitement that I felt when we were shown the documents (Picture of the Yasui House Documents).

The newly-uncovered collection of documents contained a large number of records concerning Dōtonbori’s urban development and the formation of the surrounding city area. In addition to serving as one of the district administrators of Minami District, Yasui Kuhē also held various special rights related to Dōtonbori’s neighborhoods and playhouses. Accordingly, together with letters from Oda Nobunaga and other warrior houses, the Yasui House Documents include genealogies which served as proof of the above rights, neighborhood cadastral registers known as mizuchō, large cadastral maps, and records containing information about Dōtonbori’s playhouses and smaller performance sites. Utilizing these diverse resources, let us examine Dōtonbori’s formation.

The newly-uncovered collection of documents contained a large number of records concerning Dōtonbori’s urban development and the formation of the surrounding city area. In addition to serving as one of the district administrators of Minami District, Yasui Kuhē also held various special rights related to Dōtonbori’s neighborhoods and playhouses. Accordingly, together with letters from Oda Nobunaga and other warrior houses, the Yasui House Documents include genealogies which served as proof of the above rights, neighborhood cadastral registers known as mizuchō, large cadastral maps, and records containing information about Dōtonbori’s playhouses and smaller performance sites. Utilizing these diverse resources, let us examine Dōtonbori’s formation.

2. Dōtonbori’s Development as Seen from Yasui House Genealogies

In order to understand Dōtonbori’s development, it is important to keep two things in mind. First, it is essential to consider the state of Osaka during the period immediately preceding Dōtonbori’s construction. According to existing research about Osaka’s formation, development of the city area was initiated after Toyotomi Hideyoshi began the construction of Osaka Castle in 1583. That process was carried out gradually, first along on the Uemachi Plateau and then in the Senba and Tenma areas. However, at the time, the Nishi-senba and Shimanouchi areas were still comprised of agricultural villages. As this suggests, plans for Dotonbori’s development were already in place before a large portion of the early modern city had been constructed. There was still significant distance between the site selected for Dōtonbori’s construction and the parts of the city that were already urbanized. The second thing to consider is the existence of narrow tracts of land between the Canal and the street. If one walks along Dōtonbori Canal, one immediately notices that those narrow tracts are occupied by buildings. These narrow tracts of land represent the lingering vestiges of what was known in the Edo period as hamachi, or narrow tracts of sloping canal-side land. It is vital to consider these canal sides when attempting to understand the history of Osaka canals and rivers. The Yasui House Documents include house genealogies from 1670 and 1677. These genealogies include revisions, which have been added using fūsen, or written notes layered onto existing documents. Moreover, they provide us with a basic understanding of the various stages of Dōtonbori’s development.

- In 1612, Nariyasu Dōton, Yasui Jihē, Yasui Kuhē, and Hirano Tōjirō filed a petition and began construction on the Dōtonbori Canal. At the same time, they initiated the development of canal-side residential tracts with a uniform length of 36.37 meters.

- However, Yasui Jihē soon fell ill and died, while Nariyasu Dōton perished as part of the losing Toyotomi side during the Battle of Osaka. Following the Battle of Osaka, Matsudaira Tada’akira’s chief retainer and magistrates assumed control of the city. In the ninth month of 1615, Yasui Kuhē and Hirano Tōjirō were ordered to continue developing residential tracts on both sides of the Dōtonbori Canal. By the time that the order was issued, construction of the Canal itself was already completed.

- In 1619, Matsudaira Tada’akira was reposted to Yamato-kōriyama. The Bakufu then assumed direct control of Osaka. From 1619 until the mid-seventeenth century, there were large numbers of unoccupied land parcels in Dōtonbori.

- Urban development advanced most quickly in the eight neighborhoods immediately lining Dōtonbori Canal. From the time of the Canal’s construction, Yasui Kuhē served as the area’s chief administrator. Accordingly, when Dōtonbori’s cadastral register was updated in 1655, Yasui co-sealed the document together with Hirano Tōjirō’s younger brother Tokuju. At that time, he also composed a cadastral map and submitted it to the Osaka City Governor.

Notably, Yasui Jihē and Kuhē, both of whom played a leading role in Dōtonbori’s development, were from an urban settlement connected to Kyūhōji Temple (present-day Yao-shi), while Nariyasu Dōton and Hirano Tōjirō were from Hirano County (present-day Osaka’s Hirano Ward). All four were influential figures from urban settlements in the vicinity of Osaka. Notably, influential area residents also led the construction of the canals in Osaka’s Nishi-Senba district.

3. Dōtonbori’s Tortuous Development

In addition to constructing Dōtonbori Canal, the area’s developers constructed sloping tracts of land on both sides. In addition, they installed roads on both sides of the Canal and constructed residential tracts with a uniform length of approximately 36 meters. Also, they established a series of new neighborhoods, such as Kichizaemonchō and Ryūkeimachi. These neighborhoods were communal associations of land owners.

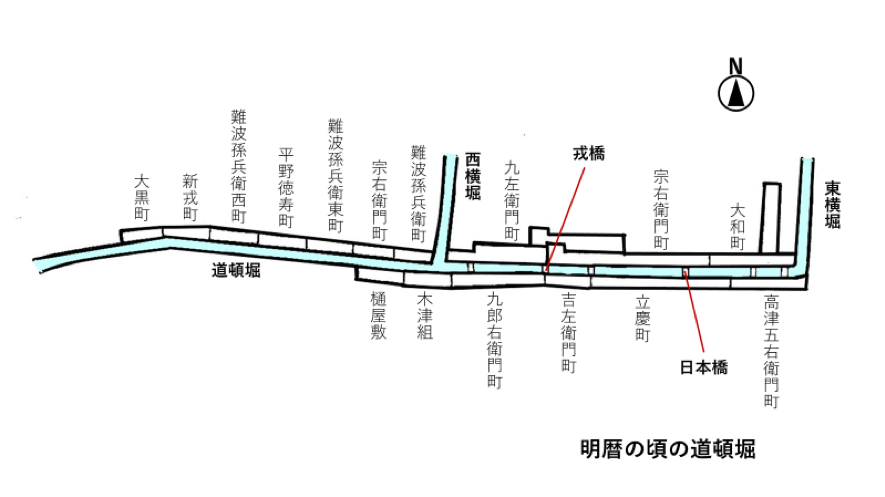

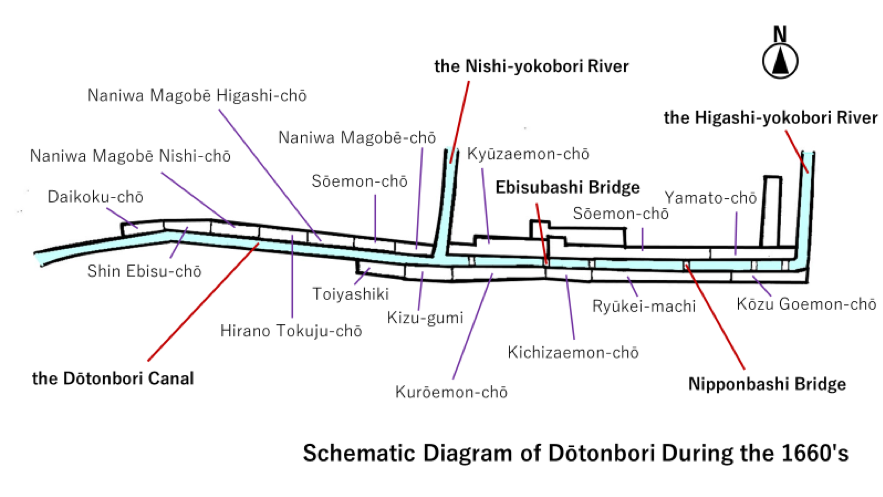

In the foregoing section, we examined Dōtonbori’s formation during the first half of the seventeenth century using the newly-discovered Yasui House documents. Now, I would like to introduce the research of Osaka Museum of History’s curator Yagi Shigeru. Mr. Yagi played a central role in the organization and analysis of the recently discovered Yasui House records and his work provides various important insights about Dōtonbori’s initial stage of development. First, let us examine the following map and schematic diagram.

As the map and diagram indicate, the development of Dōtonbori’s eastern half proceeded most rapidly. The urbanized parts of Dōtonbori were partitioned into eight neighborhoods and a chief administrator was appointed to administer local affairs. During the 1630s, however, a growing number of unoccupied residential tracts began to appear in the area. In 1640, a series of petitions requesting the right to redevelop individual tracts were submitted to the Osaka City Governor’s Office and ultimately approved. That ushered in a second wave of construction in the area. As a result, the development of the tracts of land lining Dōtonbori Canal finally reached completion. At the same time, however, lands along the eastern edge of the Canal and those along the western side of the Nishi-yokobori River remained undeveloped. In response, Yasui, Hirano, and other influential residents of Kizu, Kami-Namba, and Nishi-Kōzu Villages petitioned the city authorities for the right develop a portion of those undeveloped areas. Ultimately, their petition was approved and they presided over a process of rapid urbanization, which resulted in the establishment of a series of new neighborhoods. Once the project was complete, the men were appointed to serve as the administrators of the newly-constructed neighborhoods.

This schematic diagram depicts Dōtonbori during the 1660s, the period in which this redevelopment process took place. During the period in question, a series of new neighborhoodsーHirano Tokuju-chō, Naniwa Magobē-chō, and Kōzu Goemon-chōーwere established. Emblematic of how urban development was carried out during this period, the neighborhoods were named after the individuals responsible for their construction.

Included in the recently discovered body of Yasui House documents is a large map of Dōtonbori. The names of the individuals who owned land in Dōtonbori during this period are written on the map. This is the map.

It is actually a transcription of a Meireki-era map mentioned in Dōtonbori’s genealogy. As described in the genealogy, the map is signed by Yasui Kuhē and Hirano Tokuju. An examination of the map reveals that the Yasui and Hirano houses maintained large estates on both sides of Nipponbashi Bridge. In addition to this map, there is a cadastral register from the same period, which was verified by both men. As the foregoing discussion suggests, the newly discovered collection of Yasui House documents contains a number of valuable documents which tell us about Dōtonbori’s formation and the special rights granted to the Yasui House.

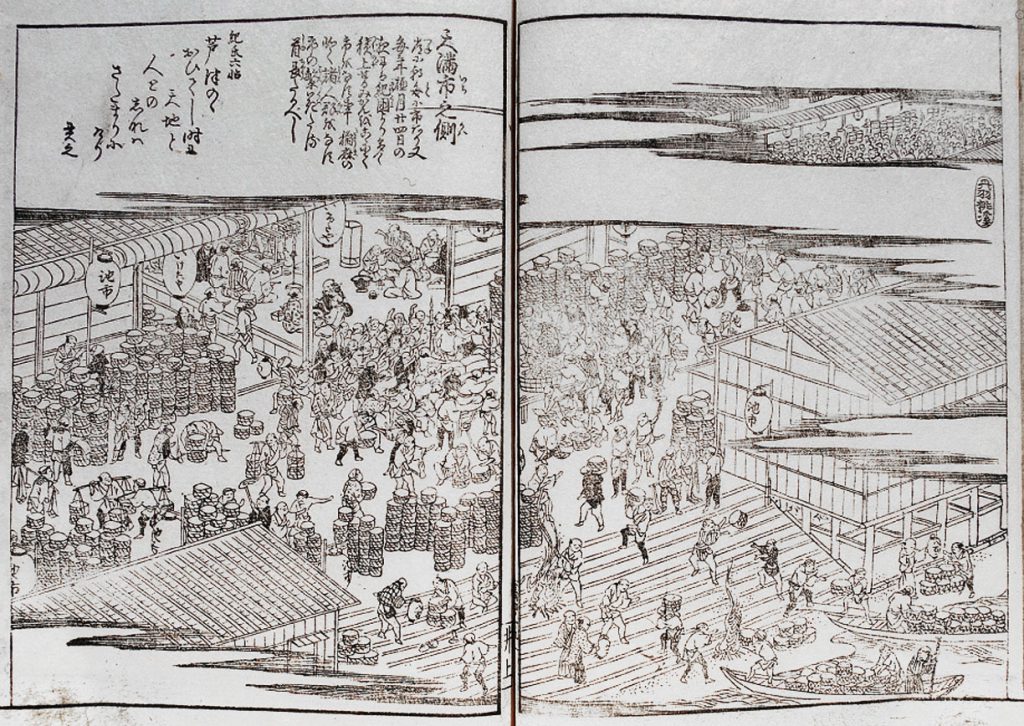

In recent years, Yagi Shigeru’s research has contributed greatly to our understanding of Dōtonbori’s development. Citing his research, I would like to mention a few additional points. First, the narrow tracts of land on both sides of Dōtonbori Canal were used as a site for offloading cargo. In addition, individuals who owned land along the Canal were given permission to use the narrow canal-side tracts of land across the street from their property. Many established canal-side storehouses on those narrow parcels. Osaka’s canal-side storehouses are depicted in various Edo-era illustrations.

They were simple structures erected over the sloping canal side, which were supported from below by wooden stilts similar to those that support Kiyomizu-dera. City regulations prohibited landowners from erecting permanent structures along these narrow canal-side tracts of land. Accordingly, individuals who erected storehouses and other structures had to be prepared to promptly remove them when ordered.

In addition, in order to bring money into Dōtonbori, Yasui Kuhē lured playhouses and performance tents to the area. In order to reward the Yasui for their efforts, a special box was permanently set aside for them at each playhouse in Dōtonbori. That box was referred to as the Yasui Box. In 1665, Dōtonbori’s playhouses began to flourish and playhouse operators determined that it was no longer sensible to leave a box open permanently for the Yasui. Instead, the House was given a pass which they could use whenever they wished to enter any of Dōtonbori’s playhouses. Over time, an additional perk―the use of a wooden tobacco tray during performances―came to be attached to that entry pass. One of the tobacco trays that the Yasui actually used has been preserved.

Early in the second half of the seventeenth century, there were 8 large playhouses and 16 smaller performance venues in Dotonbori’s Ryūkeimachi and Kichizaemonchō neighborhoods. However, by the beginning of the eighteenth century, all of the smaller venues had disappeared. At the same time, performance tents known as mizuchaya were erected in large numbers on the narrow tracts of land lining both sides of the Dōtonbori Canal.

These sloping tracts of canal side land were not unique to Dōtonbori. In fact, they were constructed along many of early modern Osaka’s rivers and canals. During the second half of the eighteenth century, however, the tracts of land lining the Horie Canal were built up and ultimately redeveloped as commoner land. These newly reclaimed tracts of canal-side land were referred to as shin-tsukiji. Similar projects were proposed in the case of Dōtonbori, as well. In 1777, for example, an influential figure from Kawachi Province’s Kuzuha Village named Nakai Mantarō petitioned the Osaka City Governor for the right to reclaim a tract of land along the south bank of the Dōtonbori Canal and redevelop it into 12.72 meters of commoner land. The residents of Dōtonbori’s eight neighborhood associations strongly opposed the project. The head of the Yasui House led the opposition effort, filing a counter petition. In order to bolster the claim of Dōtonbori’s residents, he submitted a series of house genealogies demonstrating his ancestor’s involvement in the area’s development. Three years later, after receiving a judgment was handed down by the Bakufu high court in Edo, the Osaka City Governor formally rejected Nakai’s petition. As a result, the sloping canal-side tracts of land lining the Dotonbori Canal remained in place into the late Edo period.

Summary

Generation after generation, the patriarch of the Yasui House served as one of the district administrators of Osaka’s Minami District. Osaka’s district administrators played a central role in the administration of the city’s three commoner districts. All of those houses that served as district administrator were influential urban landholders. The Yasui, of course, were one such household. In addition to playing a central role in the management of the city’s commoner districts, the Yasui House held a range of special rights in the Dōtonbori area. The Yasui House Documents contains both records related to the House’s role as Minami District Administrator and house genealogies. In addition, the collection includes a particular large number of records that were composed as a consequence of the House’s various rights and privileges in the Dōtonbori area. The character of the records produced and preserved by a specific house or social organization during the Edo period is intimately related to the house or organization’s place in the social division of labor.

Before concluding, I would like to mention two final points. The first concerns the character of Dōtonbori’s development. During the period in which Dōtonbori’s construction was initiated, urban development in Osaka was still limited to the areas shown on the Toyotomi-era map. At the time, there were still large swaths of farmland in Mitsutera and Namba Villages, which separated the site proposed for Dōtonbori’s construction and the already urbanized parts of the city. It is likely that Dōtonbori’s site was selected not only because it was already the location of a small creek, but also because it was designated to serve as the city’s eventual southern extreme. The northern portion of Dōtonbori’s eastern half was completed in 1620 as a result of the urbanization of Mitsutera Village. The newly developed area was called Shimanouchi. The development of Dōtonbori’s western half did not, however, proceed as smoothly. As the large map of Dōtonbori examined above shows, even during the late-seventeenth century, the southern portion of the area’s western half remained undeveloped. In addition, as I mentioned last session, during the late-seventeenth century, the Horie section of southwestern Osaka was still farmland. Horie’s urbanization was, however, achieved shortly thereafter with the construction of the Horie-shinchi in 1698.

Considered in light of the above discussion, it is possible to assert that the development of the Dōtonbori area was part of a broader process of urbanization, which included the simultaneous construction of a series of canals in the Nishi Senba area. Also, permitting the operation of licensed playhouses and teahouses in Dōtonbori in order to promote economic vitality is a technique that the early modern authorities utilized during later periods when attempting to encourage the development of the Horie and Sonezaki areas.

The final point concerns hamachi, or the narrow tracts of land that lined Osaka’s canals and rivers. As mentioned above, if you visit Dōtonbori today, you will notice that there are long, narrow slivers of land lining both sides of the canal. The origin of those narrow tracts of land can be traced back to Edo-period Osaka’s sloping canal sides. During the Meiji period, canal-side lands came under individual ownership. Although Dōtonbori’s canal sides were built up and partially reconstructed during the 1960s, it is possible to observe in present-day Dōtonbori the continuing influence of the Edo-era spatial structure on the contemporary built environment. Furthermore, the vitality and prosperity of present-day Dōtonbori can be said to be an extension of early modern policies of urban development which transformed the area into a center of entertainment where large groups of people congregated.