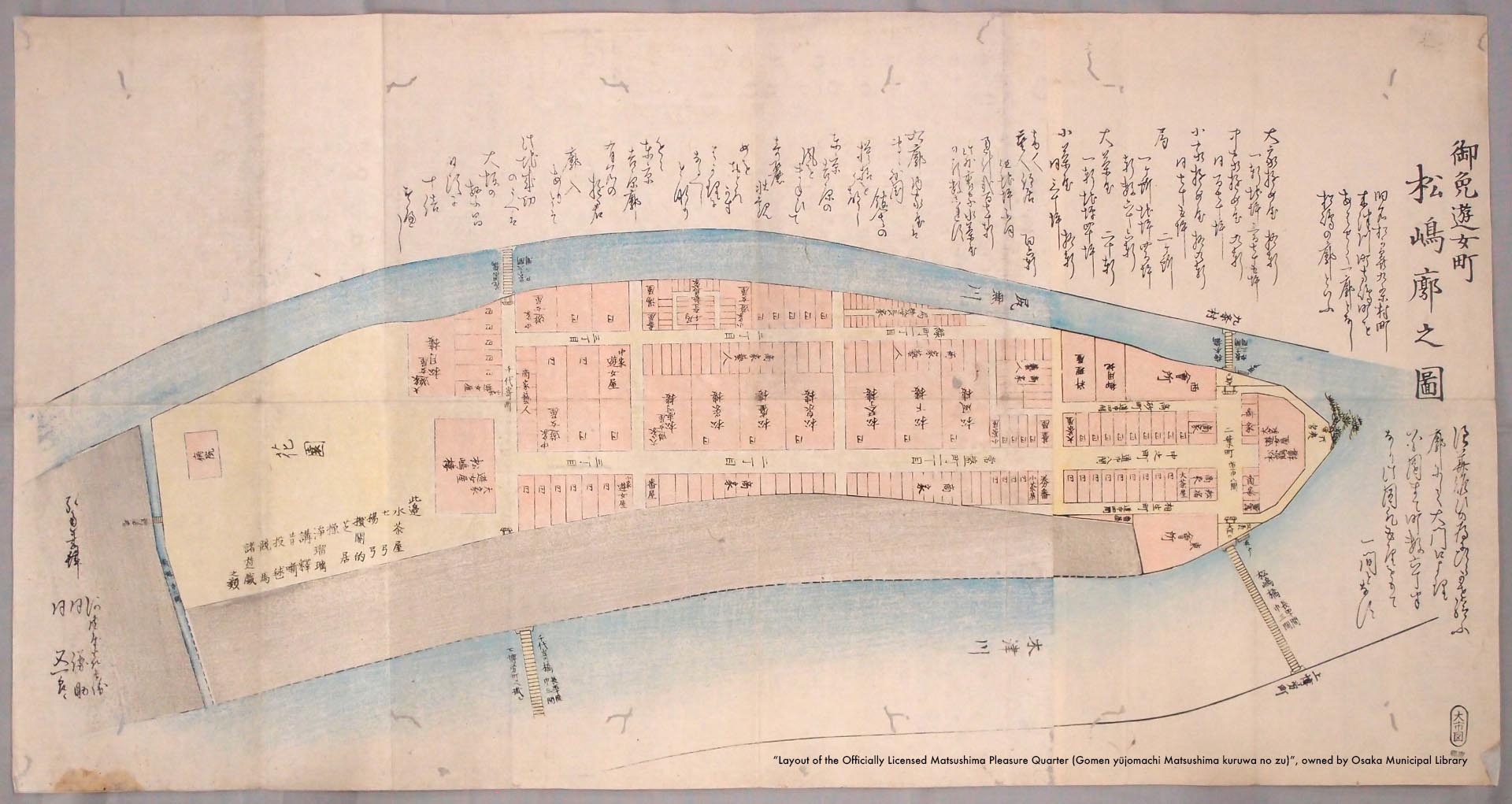

Hero Image: “Layout of the Officially Licensed Matsushima Pleasure Quarter (Gomen yūjomachi Matsushima kuruwa no zu)”,

owned by Osaka Municipal Library

Introduction

Hello, I’m Saga Ashita, a professor at Osaka City University. Starting today we’ll be entering into the modern period.

In today’s class I’ll first provide a general overview of the effects the Meiji Restoration had on Osaka. Working off that, I’ll then introduce some concrete examples of the highly particular local social formations that helped define the larger urban society of Meiji-period Osaka.

Recent work in urban social history has given us a few important considerations to keep in mind during our examination of urban society in the Meiji period: first, the need to pay careful attention to both the continuities and the discontinuities with the early modern period; second, to look at urban formations from a spatial perspective; and third, the importance of reconstructing the everyday lives and social connections of people in specific urban localities and social groups.

Keep these points in mind as we go through today’s class.

1. Osaka and the Meiji Restoration

Naturally, the Restoration gave rise to big changes in Osaka. In the first month of 1868 (old calendar), Ōkubo Toshimichi called for the relocation of the capital to Osaka as the new government, dominated by Satsuma and Chōshū domains, brought the city under its control. The reflected the political ascendance that the neighboring poles of the Kansai region, Osaka and Kyoto, had experienced over the Bakumatsu period (the final years of the Tokugawa Shogunate). The relocation didn’t happen in the end, but Osaka did rapidly take on important roles, first as Japan’s base for diplomatic negotiations when, later in 1868, the Foreign Office was set up there, and then as home to the Mint, from 1869, where the new government produced its coinage. However, Osaka’s economy suffered two successive body blows with the actual move of the capital to Tokyo later in 1869, and then the abolition of the silver ginme currency in 1870 (in the early modern period the Edo area used gold and Kansai silver). Further, the city’s political position steadily declined as governing authority was centralized in Tokyo. The most radical departure in this regard came with domain abolition in 1871 (haihan chiken), through which the plethora of relatively independent Edo-period domains (han) was replaced with (eventually) a far smaller number of subordinate “prefectures” (ken). Osaka’s population, which had reached over 400,000 in the Edo period, also declined for a time.

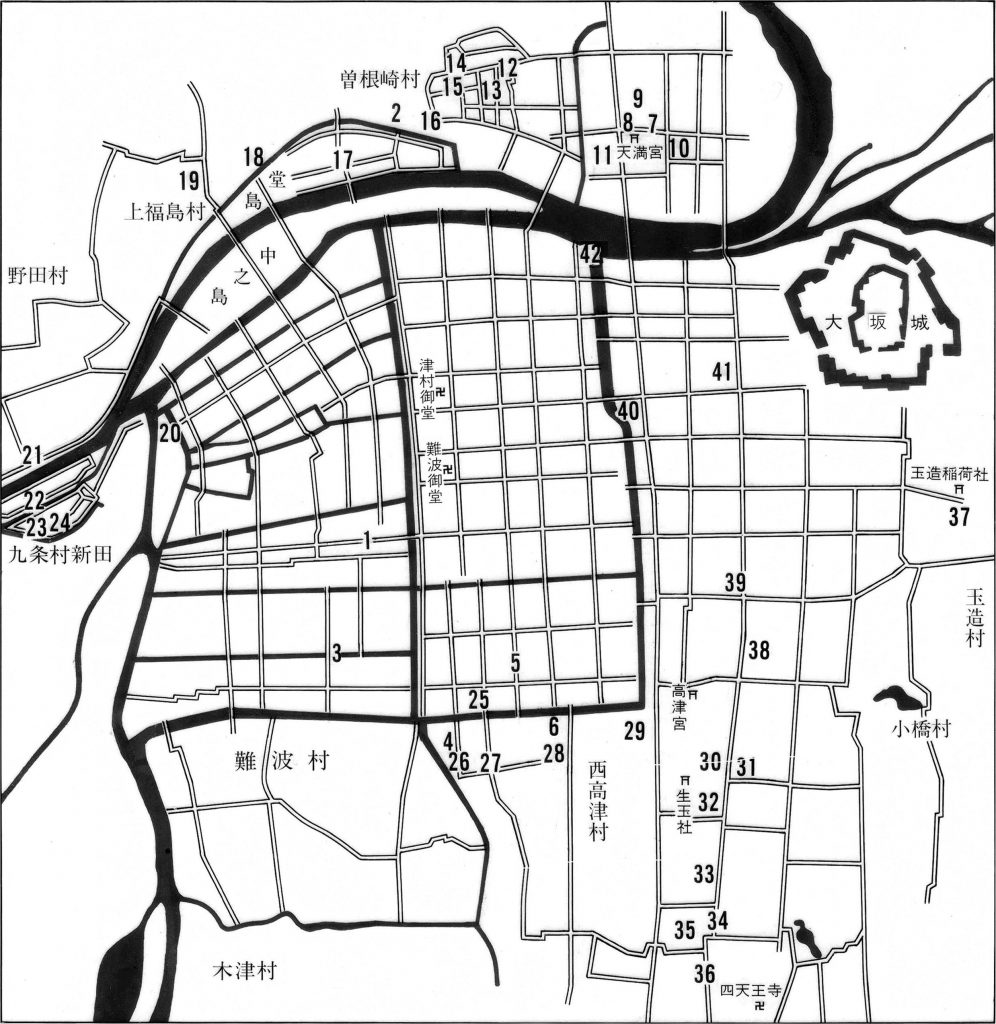

Of course, there were also various changes in Osaka at the level of urban society. As an example of those changes, we’re going to look at the Kawaguchi foreign settlement and the Matsushima brothel district that was attached to it. Both were new, products of the Meiji period, but the process by which they came to be and the course of the events that followed were heavily influenced by early modern social structures. So now let’s dive into this locality, keeping eyes on both the changes wrought by the Restoration and the deep-rooted persistence of early modern social forms.

2. The Kawaguchi Foreign Settlement

① The Social Structure of the Kawaguchi Foreign Settlement

First, let’s take a look at the events leading up to the establishment of the settlement in 1868. The Ansei Five-Power Treaties of 1858 (with the US, UK, France, Russia, and the Netherlands) stipulated that Osaka be opened as a market (kaishi). The deadline was pushed forward once, but on January 1, 1868 the Osaka market opened together with the port in neighboring Kobe. In September of the same year, Osaka’s port was opened as well, the land at Kawaguchi auctioned off, and the settlement formally established.

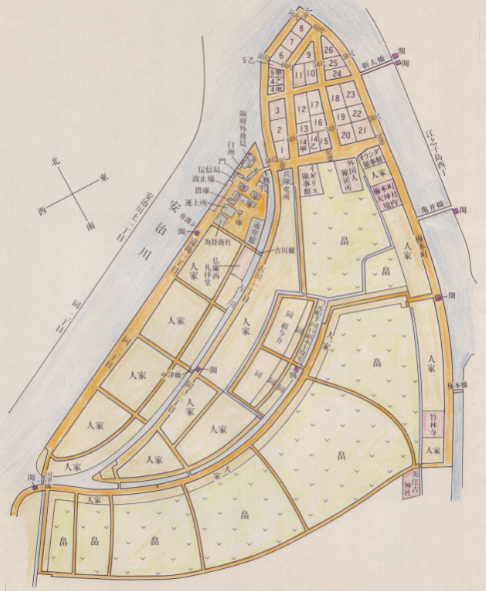

Kawaguchi comprised the western edge of the city’s built-up area (i.e., on Osaka Bay). In the early modern period, it hosted shogunal guard stations for inspecting cargo coming into Osaka, branch offices of the House of Hitotsubashi (relatives of the Tokugawa), and the like; in short, the area was defined by a high concentration of official/“public” facilities. It was this character that influenced the choice of location for the development of the foreign settlement.

owned by the Office of the Editor for Osaka City History

What foreigners from the treaty countries purchased at auction (and so became “owners” of) was actually perpetual lease rights to land. The Japanese government provided deeds to that effect and collected rent from the rights holders, but the rights themselves could be bought and sold freely thereafter. The money from the initial auctioning of these rights, along with a portion of each year’s rents, was set aside as an endowment fund for the administration of the settlement.

In terms of spatial structure, the foreign settlement was divided in two. First, in the strictest sense of a foreign settlement, the area where foreign “owners” (i.e., perpetual leaseholders) lived. Here Japanese were not allowed to own/rent land and internal governance was left to the newly established Osaka Foreign Settlement Municipal Council (I’ll come back to the Council and the endowment fund shortly).

Second was the mixed residential area, which abutted the settlement proper and was also open to foreign residence, but on different terms: foreigners, including non-Westerners, lived amongst Japanese people and rented their lodgings from Japanese owners. Over time, these mixed areas became home to large numbers of Chinese (i.e., Qing subjects).

The makeup of the Western residents by country and occupation

in the Kawaguchi Foreign Settlement

| Great Britain | United States | Prussia | Holland | France | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 29 |

| Year | Commerce | Technican | Teacher | Doctor | Missionary | Diplomat | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1872 | 27 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 63 |

| 1887 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 67 | 2 | 2 | 86 |

Now let’s turn briefly to the makeup of the settlement’s Western residents in the early years of Meiji. If we look at perpetual leaseholders by country around 1870, British were most numerous, followed by Americans, then Prussians, and so on. By occupation, using statistics from 1872, a large number of foreigners were involved in commerce of some kind, followed by technicians, doctors, etc. However, by 1887 missionaries made up the overwhelming majority, with very few commercial agents and technicians.

(hence the large numbers of businesspeople). But because of the excessive silt that the Yodo River deposited each year around the jetties, the area was eventually judged inappropriate for that purpose. Idle foreign settlements being the devil’s workshop, the number of missionaries increased, transforming Kawaguchi into a base for proselytization and educational activities.

② Self-Governance in the Foreign Settlement

in St. Andrew’s Archives

As I mentioned before, the Kawaguchi foreign settlement had its own governing body, the Osaka Foreign Settlement Municipal Council. It began with the establishment of the endowment fund system in the “Osaka-Hyogo Foreign Settlement Agreement” of August 1868. This agreement stipulated that the management of the fund be carried out by a council made up of the governor of Osaka Prefecture, each treaty power’s ambassador, and three lease-holding representatives. The first election for these representatives was held in October and the Council’s first session in May 1869, in the home of the Dutch vice consul.

In total, 126 sessions were held, the last in July 1899 (Meiji 32), which was the year that foreign settlements were abolished. The Council dealt with all matters related to the management of the settlement, such as roads and sewage, firefighting, public safety and hygiene, the cemetery and parks, etc. To give illustrate the degree of self-governance in the settlement, let’s briefly look at firefighting and police.

The settlement’s fire brigade got its start in 1875, the Council having purchased a steam-powered pump from Britain in 1874, after which point residents themselves carried out the brigade’s activities.

Further, the council set up a police board in 1869, and from 1874 until the abolition of the settlement, Englishmen served as chief of police.

As you can see, the foreign settlement council had the authority over its internal affairs and maintained its own police and fire departments, ultimately on the basis of the extraterritorial rights established in the commercial treaties concluded with Western countries.

③ The Foreign Settlement and Related Facilities

Despite extraterritoriality, the Kawaguchi foreign settlement did not exist in isolation: many associated facilities and services took shape around it.

First of all, there was the foreign cemetery in Zuikenyama, a part of the Ikeyama shinden (lands reclaimed for rice agriculture) slightly down the Aji River from the settlement.

The Jiyūtei, a Western-style hotel referred to by the Japanese as the “foreigners’ lodge,” opened in 1868 in the Umemoto-chō neighborhood of the mixed residential zone. To serve the demands of meat-heavy Western diets, a slaughterhouse was built in the Ishida shinden (along the banks of the Aji River) on land the government had bought up and leased to an Englishman. Last, but certainly not least, the Mastushima brothel district was opened specifically for foreigners.

In sum, the Kawaguchi foreign settlement constituted a zone of extraterritoriality within Osaka, where, on the basis of the unequal treaties, foreigners’ self-government was permitted. But it also exerted a great influence on local society because of the various derivative facilities and services that it called into being. Foreign settlements were abolished in 1899, when revised commercial treaties came into effect that rescinded the rights of extraterritoriality and permitted mixed residence throughout Japan. Accordingly, the grounds of the settlement in Osaka were integrated into the city as a part of the Kawaguchi-chō district.

3. The Matsushima Brothel District

① Basic Character and Spatial Structure

Now let’s take a look at Matsushima, not just as an element of society in the foreign settlement, but also with attention to its connections to the surrounding local society and the history of Edo-period brothel districts.

In 1867, the Osaka Magistrate, Shibata Takenaka, submitted a proposal to the shogunal elders for a brothel district serving foreigners to be established as one of the facilities attached to the planned foreign settlement. After the settlement opened in the tenth month of 1868, the Foreign Office, which the Restoration government had set up in Osaka, began preparations for just such a brothel district. There was some local resistance because the authorities bought up, and vacated residents from, the designated land over just two months. Nonetheless, by the twelfth month they had named the site “Matsushima-machi” and begun recruiting prospective brothel operators. The establishment of the new brothel district thus proceeded, with extreme speed, as a development project of the areas surrounding the foreign settlement.

We can summarize the basic character of the new brothel district as follows:

- It was legal and officially sanctioned (gomen yūjomachi), built on government land (managed by the Foreign Office) essentially as an annex to the Kawaguchi foreign settlement.

- Its purpose was to provide sexual services to foreign sailors and laborers, etc., thereby preventing sexual contact between foreign men and the general population of Japanese women.

- the Matsushima brothels were set up as “branches” (demise) of the Edo-period brothels that had operated out of the Shinmachi district, officially licensed by the shogunate for such activities, or other unofficial locations (whether tacitly permitted or completely illicit).

These special characteristics set Matsushima apart from preexisting brothel districts.

Next let’s have a look at a layout drawing that shows the spatial layout of Matsushima.

owned by Osaka Municipal Library, partial modification

First we should note how the preexisting built-up area on the east side of Terashima (the island) fell outside the enclosure that demarcated the brothel district. Second, four new bridges and gates were built, along with east and west meeting halls, and other sites for official business. Third, there was the Shōkaku Pleasure House, a grand structure crowned with a small tower, which was built by the government and rented out to brothel operators (otategashi). We also see how Matsushima was envisioned as a space where businesses would be compartmentalized according to both type of occupation and class: the brothels themselves, divided into four ranks; chaya “tea houses” large and small, serving as intermediaries between brothels and customers; sections for merchants, entertainers, tea stalls, etc. Finally, the large open space on the south side labelled “Hanazono” provided a space for temporary attractions like archery and theater.

As you can see, this illustration allows us to pick out several of the defining features of the Matsushima brothel district.

② Osaka’s Brothels and the Transition to the Modern Period

The Matsushima brothel district became a keystone in the regulatory framework that was erected to govern Osaka’s preexisting Edo-period brothels, which included the officially licensed Shinmachi area as well as multiple tacitly permitted operations.

owned by the Office of the Editors for the Osaka City History

In the tenth month of 1872, the Meiji government promulgated the Entertainer and Prostitute Emancipation Act (geishōgi kaihōrei). It forbade the sale and purchase of persons as a source of labor for such operations, which had been general practice during the Edo period under the pretext of adoption or indentured servitude. However, the sale of sex itself was not banned. Ergo bondage to a brothel became illegal, but not the selling of sex (and entertainment) that occurred with the providing individual’s consent. The Act still pulled the rug out from under brothel districts throughout Japan, but Osaka’s response was noteworthy. In Osaka, the government had already developed a policy a year prior of preserving large-scale brothel districts like Shinmachi and Matsushima, using the latter as a receptacle for consolidating the city’s many petty, tacitly permitted brothel operations. This was also a means of promoting business in Matsushima. An so, following the promulgation of the Emancipation Act, Osaka immediately decreed Shinmachi, Matsushima, and four other Edo-period brothel districts to be licensed for the “space rental” trade (sekigashi)—in other words, the business of providing newly emancipated sex workers with places to operate.

In sum, the regulation of brothel districts in Osaka underwent a major shift through the municipal government’s strategies for promoting Matsushima, and these in turn shaped the modern system of legal prostitution in the city.

③ The Matsushima Brothel District and Local Society

In closing, let’s look at Matsushima’s connections with local society.

Provisionally, we’ll call the land area of the island where the brothel district was located the Matsushima area. The built-up area on the eastern side, Matsushima-chō, dated from the Edo period and was dominated by boathouses, boat builders, and the like. During the construction of the brothel district, the land owners and boat builders from this area opposed the government’s buying up of land and the building of new bridges. But when the new bridges made ferry services obsolete, former operators petitioned for, and were granted, monopoly rights over the transport of goods and provision of water to the brothels. Basically, at first there was opposition to the establishment of the brothel district, but when that became unavoidable, people came to rely on it as part of their livelihood.

Eventually, in order to accommodate patronage by government forces shipping out of Osaka during the Satsuma Rebellion, the brothel district’s borders expanded, swallowing up the normal town area on the island’s east side. In terms of the power relations between the town and brothel areas, originally born out of resistance and then reliance, we can therefore say that the latter came to dominate the whole of the local society.

As we have seen today, the Matsushima brothel district, which began as a development of the area around the Kawaguchi foreign settlement, evolved historically through the interaction of a variety of factors, including central and local government policies of brothel regulation and business promotion, transformations within the sex trade, and the district’s multifarious subtle connections with local society. When the foreign settlement began to stagnate, its connection with the brothel district weakened and Matsushima became more and more independent of its influence, eventually growing into a force that would direct the development of the entire local society. In the persistence and evolution of brothel districts despite the Emancipation Act, we can see the entrenched nature of the social connections that early modern Japanese society had brought into being.

Thus while it does, at first glance, look as though urban Osaka changed greatly with modernization, in fact Edo-period structures remained deeply rooted, shaping the conditions of local urban society. We must, therefore, understand modern urban society as an entanglement of old and new elements.