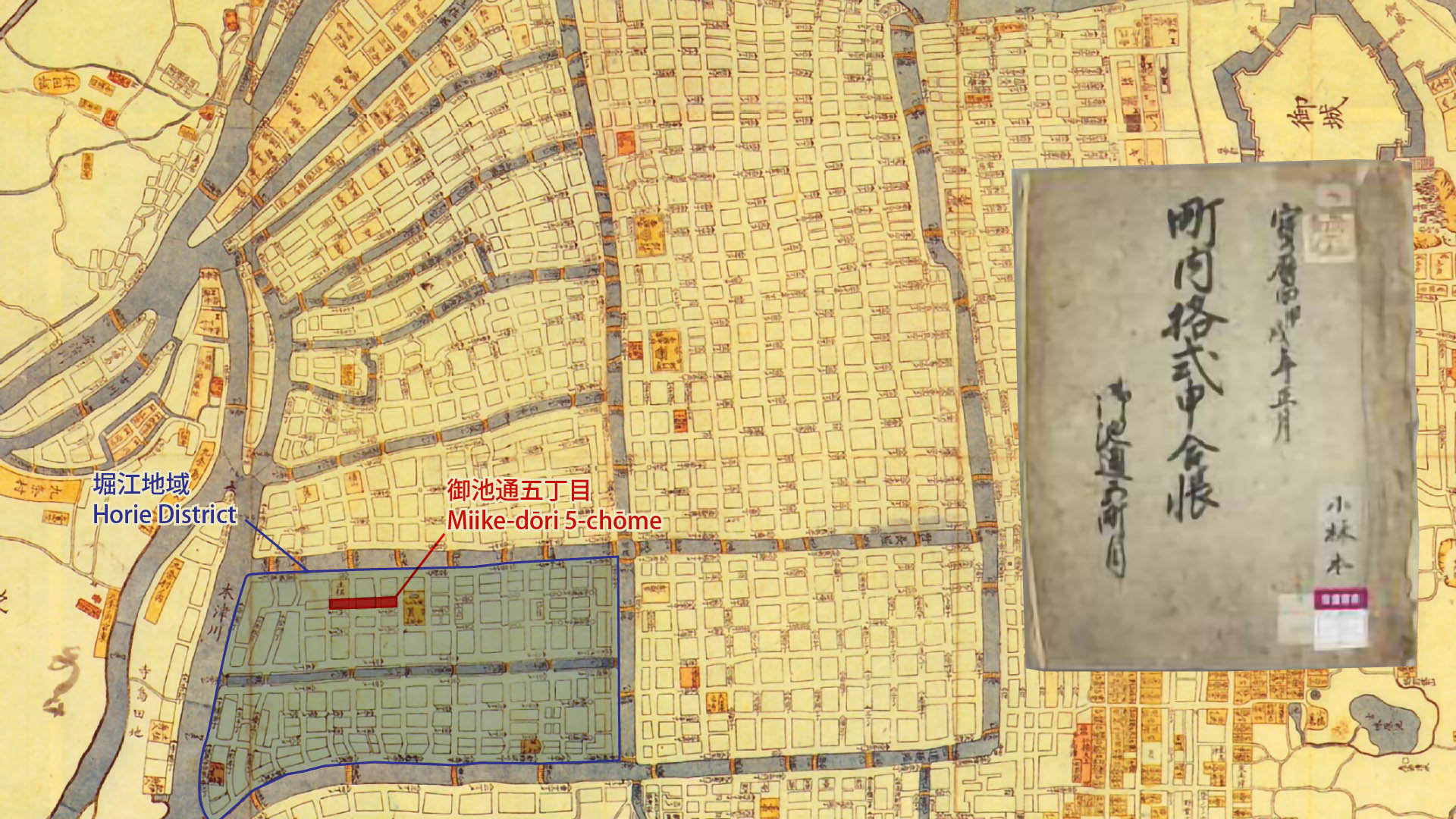

「文政新改摂州大阪全図」 (大阪古地図集成 第12図)より

Source: The Newly Revised Map of Bunsei-Era Osaka

(The Osaka Municipal Library’s Online Collection of Archival City Maps・Map 12)

※大阪市立図書館デジタルアーカイブ

※The Osaka Municipal Library Digital Archiveをもとに加工

【Explanation】

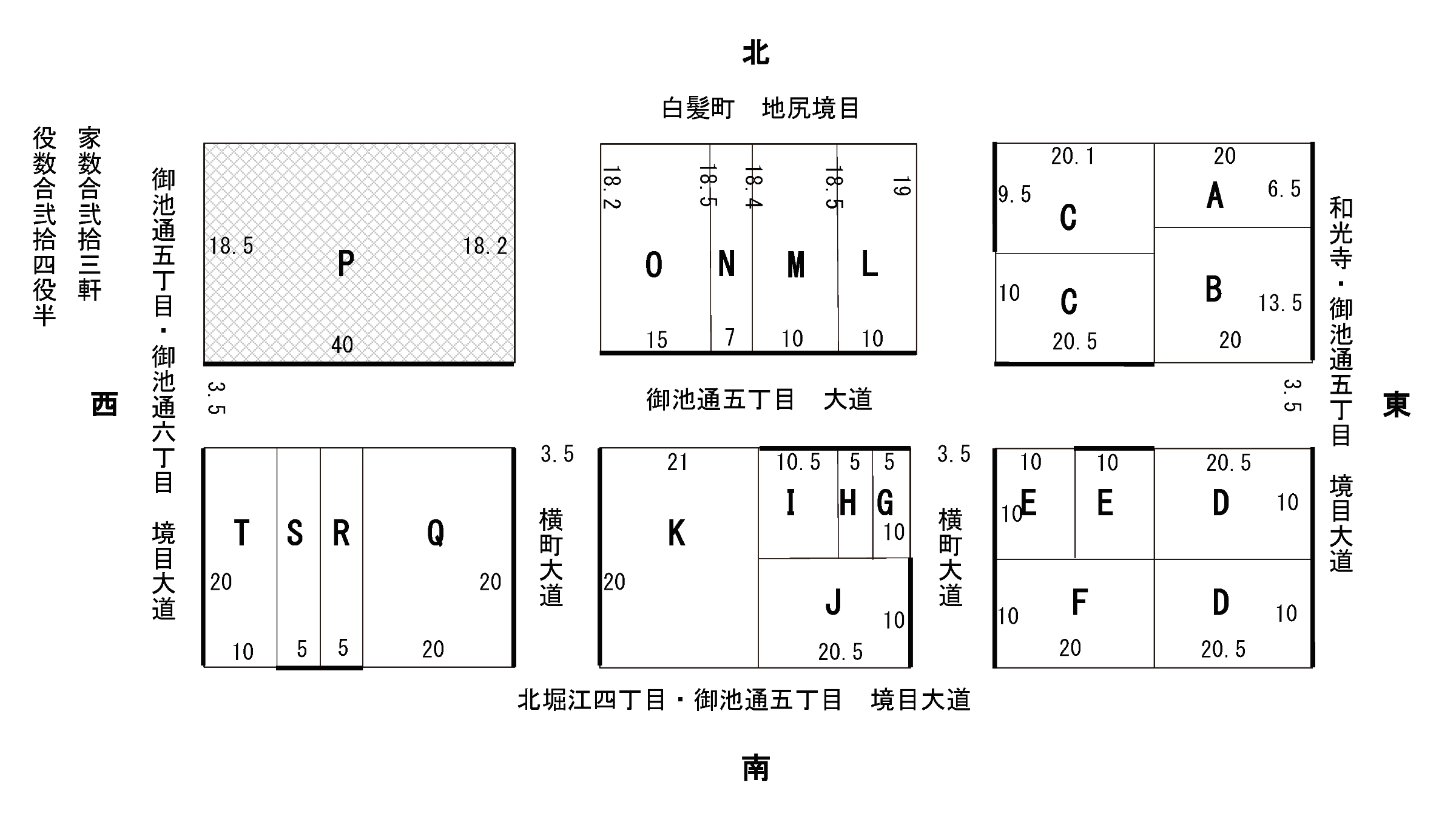

The document examined in this lecture is a Register of Block Association Rules and Agreements (Chōnai kakushiki mōshiawase chō 町内格式申合帳) composed in the first month of Hōreki 4 (1754) by the constituents of the Miike dōri 5-chōme block association. One of Osaka’s approximately 630 block associations, Miike dōri 5-chōme was located in the city’s Horie district (See the map below). Although Miike dōri 5-chōme was formally established in Genroku 11 (1698), its layout has been recreated using the Bunsei 8 (1825) Miike dōri 5-chōme Cadastral Map (Miike dōri 5-chōme mizuchō ezu) (See Map 1). As this map reveals, the Miike dōri 5-chōme block association was comprised of three dual-sided 72.2 meter (40 ken) blocks lining Miike dōri Road.

Map 1 Miike dōri 5-chōme Cadastral Map (Miike dōri 5-chōme mizuchō ezu)

Map 1 is a modified version of Map 5 from Yoshimoto Kanami’s 2018 article “The Structure of the Block Association in Early Modern Osaka’s Horie District: An Analysis of Cadastral Records from Miike dōri 5-chōme”(Buraku mondai kenkyū, Vol. 225). Map 5 was produced using a cadastral map attached to the Bunsei 8 Miike-dōri 5-chōme Cadastral Register, which is currently stored in the Osaka Central Municipal Library archives.

※The numbers indicate the width of individual properties (ieyashiki) and major roads (daidō). The unit used to measure width is the ken. The bold lines indicate the front side of each property.

※The letter attached to each property corresponds with the letter of the owners listed in Table 1.

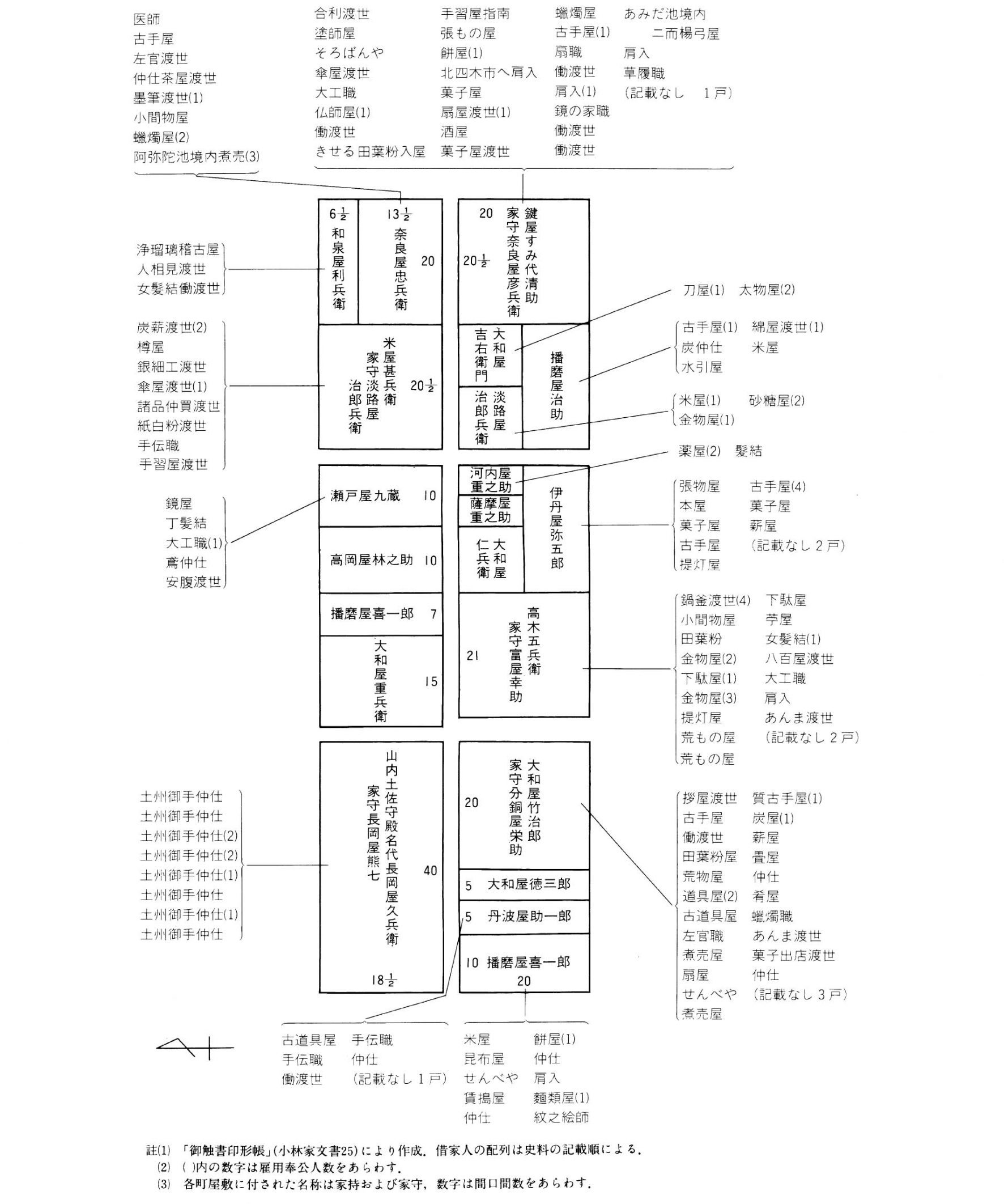

※The gray-shaded lot in the upper lefthand corner of the image is the site of Tosa Domain’s Osaka Depot.

Table 1 indicates the composition of each landowner’s household and number of tenants on their property. It was composed using the Miike dōri 5-chōme population register from the tenth month of Bunsei 10 (1827). Properties in which no family members and servants are listed indicate those owned by landholders residing in other block associations(tachōmochi) who employed on-site caretakers (yamori). The occupations of block association tenants are listed in Table 2. Although it is clear that Miike dōri 5-chōme’s tenant stratum included both front-street tenants (omote tanagari), who rented properties lining the block association’s streets, and rear tenants (ura tanagari) residing in back-alley dwellings, precise details about their number and dispersion are unavailable. It is important to distinguish between these two types of renters because the type of dwelling in which they lived determined whether or not they were able to earn a living within the block association. Front-street dwellings included commercial spaces, where residents could engage in some sort of trade. It is likely that residents engaging in specific forms of on-site commerce, such as the sale of used goods(古手屋furuteya) and sundries (小間物屋komamonoya), rented front-street dwellings, whereas those working outside the association in occupations, such as heaver (仲仕nakashi), casual laborer (働渡世 hataraki tosei), and construction laborer (手伝 tetsudai), lived in back-alley units. Research on the history of both renter types has revealed that there were significant socio-economic disparities between front-street tenants and the residents of rear units. It is likely that this was also the case in Miike dōri 5-chōme.

| Owner | Owner’s Family | Servant(M) | Servant(F) | Tenants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| B | 2 | 4 | 2 | 12 |

| C | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| C (Caretaker) | 18 | |||

| D | 29 | |||

| E | 7 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| F | 8 | |||

| G | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| H | 3 | 4 | ||

| I | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| J | 3 | 3 | 1 | 13 |

| K | 21 | |||

| L | 4 | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| M | 16 | |||

| N | 4 | 5 | 2 | |

| O | 26 | |||

| P | 9 | |||

| Q | 26 | |||

| R | 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| S | 4 | 1 | 8 | |

| T | 4 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

Table 1 The Composition of Landowners’ Households and Number of Tenants on Each Property

Source: The Bunsei 10 Miike dōri 5-chōme Population Register (Osaka Municipal Central Library Archives, Kobayashi House Documents 81)

Table 2 The Occupations of Miike dōri 5-chōme’s Tenants (Meiji 1)

This data is taken from Nishizaka Yasushi’s article “Osaka Miike-dori 5-chome,”

which appeared in An Introduction to Japanese Urban History, Volume 2: Block Associations (Tokyo University Press).

Keeping the foregoing analysis in mind, let us now examine the Register’s form and content. Comprised of 28 articles, the document is sealed by both the association’s landowners and caretakers. The seals signify a pledge on the part of landowners and caretakers to uphold the provisions detailed in the articles. The Register states that its articles represent “established rules and formalities,” enabling us to conclude that the document was composed in order to reconfirm existing association regulations rather than create new ones. It is also important to note that the document is sealed only by landowners and caretakers, and does not include tenants’ seals. In other words, it represents an agreement concluded by individuals formally permitted to participate in block association administration and does not include parties under the association’s authority.

The names of the document’s original signatories are obscured by paper codicils, which were added to the Register at a later date to indicate changes in the composition of the block association’s membership. The name of the last block association administrator (toshiyori) indicates that the document was last sealed in or after Ansei 2 (1855). At the time, five caretakers were included among the signatories. In addition to telling us that the Register was in use until the end of the Edo period, it also hints that, from the time of its production, caretakers were included among the document’s signatories. Caretakers were not, however, full-fledged constituents of the block associations. Rather, they sealed the document in place of a specific absentee landholder whose interests they were representing. In the attached translation of the document, rules intended specifically or caretakers include the term “caretaker,” whereas provisions that refer to the block association in its entirety indicate regulations for both landowners and caretakers.

Let us turn now to the details of Register itself. The first three articles contain provisions related to Bakufu Law, such as the Three-Article Pledge (Sankajō shōmon) (Article One) and Register of Religious Affiliation (Shūshi ninbetsu chō) (Articles Two and Three). Although these three articles represent common provisions, which were included in many status agreements, they tell us much about the block association’s character and structural features.

The Three-Article Pledge mentioned in article one refers to a document known as a shūshi maki*¹, which contained three rules that all block association residents were obligated to uphold. Landowners and caretakers were required to seal the Pledge each month, thereby certifying that residents would refrain from practicing Christianity or engaging in unlicensed prostitution or gambling. In the case of Miike dōri 5-chōme, local regulations mandated that landowners and caretakers should meet at the block association office during the fifth hour (around 8:00 AM) of the first day each month and jointly seal the document. Although the provision concerning the Pledge somewhat ambiguously states that “the entire association” should assemble, it is clear that only landowners and caretakers actually attended the monthly gathering. It also states that all of the signatories would, of course, uphold the “Three Articles” and that all tenants under their authority would be made to follow them. The fact that tenants were viewed as subordinate actors who should be “made to uphold” the foregoing regulations indicates that that they were not considered full-fledged association constituents.

*1 Translator’s Note: As mentioned above, the term shūshi maki is directly translated as Register of Religious Affiliation. However, shūshi maki can be accurately described as a “Three-Article Pledge” confirming that there were no Christians, prostitutes or gamblers residing within the association.

When association constituents assembled each month, they also discussed association affairs (chōgi). In other words, monthly assemblies during which block association constituents gathered to seal the Three-Article Pledge also served as occasions for association meetings (chōchū yoriai), where administrative matters were discussed. As we noted above, it is important to recognize the socio-economic differences that distinguished front-street tenants from renters living in rear dwellings. The two groups were similar, however, in that, as renters, they were prohibited from participating in block association administration. That said, a framework that neglects to distinguish between front-street and back-alley tenants fails to accurately grasp the social structure of the early modern block association.

Article two stipulates that everything – from the births of children, adoptions, and marriages of landowners or “the lowest tenants,” to the hiring, births, and deaths (in most cases, only deaths) of servants – should be fastidiously recorded in the Register of Religious Affiliation. Article three prohibits individuals whose names are not listed in the Register from staying in the block association. It states, however, that when such a situation was unavoidable, the name of the unregistered person should be reported to the association administrator and recorded. These provisions, too, indicate that only landowners and caretakers were permitted to participate in block association administration and tenants were under their authority.

Article four prohibits association constituents from traveling to another outside of Osaka during months in which they were serving as monthly representative. When doing so proved unavoidable, the article states that the matter should be discussed with the block association administrator and other monthly representative, and that alternative arrangements should be made. As discussed in a previous lecture, monthly representative was an alternating position filled each month by two landowners or caretakers. This article indicates that the position of monthly representative was a duty that landowners and caretakers had to perform, and was likely quite burdensome for merchants and others who had to do business outside of Osaka.

Article five concerns the resolution of disputes involving association residents. It states that the association administrator, five-household association (goningumi), and landowner (ienushi) should meet, investigate the circumstances, and attempt to find an internal solution. If the disputing parties were formal association constituents, responsibility to resolve the issue fell to the association administrator and relevant five-household association(s). If they were tenants, the administrator and relevant landowners or caretakers were given that responsibility. This provision applies to both landowners and tenants.

In contrast, articles six, seven, and eight clearly stipulate landowners’ regulatory responsibilities towards tenants living on their property. Article six states that landowners should caution their tenants to ensure that they were careful with fire and refrained from allowing suspicious persons on the property. Article seven requires all landowners and caretakers to evict insolent and insubordinate tenants, and prohibit them from obtaining a dwelling anywhere else within the association. Article eight orders landowners to confirm the new addresses of all persons leaving the association, and obliges new tenants to submit proof of religious affiliation (shūshi tegata) to the association office in order to secure a dwelling. These articles indicate that renting out parts of one’s lot was more than simply an economic action. Landowners who did so were also required to perform specific administrative tasks related to the regulation of their tenants. Article nine requires persons moving away from Osaka to obtain permission from the City Governor. In other words, procedures governing relocations within Osaka and those concerning relocations to another region were different. Notably, this article was added to the Regulations in accordance with a proclamation from the Osaka City Governor.

Article ten prohibits the construction of earthen storehouses (dozō) in the front of lots because doing so would adversely affect the association’s physical appearance. However, this provision was amended (via a paper codicil) in the fifth month of Kansei 4 (1792) after a citywide proclamation (machibure), which stated that “earthen storehouses should be constructed in the front and rear of lots” for the purpose of fire prevention.

Next, articles eleven and twelve concern the buying and selling of properties. First, article eleven requires landowners planning to sell their lots to notify the block association before concluding a sale. Provisional contracts (tetsuke shōmon), the article notes, should be arranged only after receiving association permission (chōchū wagō no ue 町中和合の上). In other words, individual owners were required to receive the approval of the block association even when attempting to sell personal properties. This is because ownership of a property within the block association meant that its possessor was also a formal association constituent.

Article twelve prohibits the sale of lots individuals engaging in specific professions. For example, owners were prohibited from selling their properties to merchants dealing in or producing*² lime (ishibaiyaki 石灰焼), those selling tanned deer leather (shiragawa) or hides colored by smoking (fusubekawa) (or glue and gelatin), those offering housing to or acting as intermediaries for potential servants (hitoyado hitouke shōbai), those who transported goods by horse (umakata shōbai), teahouse or bathhouse operators, smiths making kettles (yakan kaji) or casting metal objects (imoji), smiths producing anchors (ikari kaji), oil producers (shibori abura), those selling beef tallow or candles made from beef fat (gyūrō), those selling human waste, those selling funeral goods, or to True Pure Land (Jōdo Shinshū) temples or practice halls. Additionally, landowners were prohibited from using their properties as collateral when borrowing money from people in these professions, as failure to repay a loan would result in a transfer of ownership rights to the lender, which, in turn, would give them formal standing as an association constituent. Notably, landowners were prohibited from selling properties individuals who had at some point engaged in the operation of a teahouse or bathhouse, even if the buyer was not currently doing so. In addition, although this article bars associations constituents from selling their properties to or borrowing money from individuals engaging in any of the foregoing occupations, it does not ban them from leasing dwellings to such individuals. This type of employment-based regulation differed from block association to block association, and individual associations implemented their own occupational restrictions.

*2 Translator’s note: Concerning the multiple meanings of shōbai here, see the footnote in the corresponding section of the translation of the document above.

Taking this point as evidence, Asao Naohiro points out that the block association, along with the village, was one of early modern Japan’s basic social organizations, and that membership in an association was ultimately based on the mutual recognition of association members. Furthermore, he defines the block association and village as territorially- and occupationally-bonded status groups.*³ Evidence contained in the Register, however, suggests that the authority of association restrictions was not always absolute. An interesting example concerning this point can be found in article 28, which concerns the case of Shibushiya Yoichirō.

*3 Asao Naohiro “Kinsei no mibunsei to senmin,” Buraku mondai kenkyū 68, 1981.

According to the article, Shibushiya wanted to transfer ownership of his lot to an employee (tedai) by the name of Kanbē. After discussing the matter with other members of the association, however, he was informed that existing association rules stipulated that only immediate family members and cousins were permitted to inherit property within the association, and that properties could not be transferred to employees. However, because Shibushiya repeatedly petitioned the association for the right to do so, association administrator Nagaokaya Kyūbē ultimately agreed to act as an intermediary and help him move forward with the transfer. Nagaokaya proposed that Shibushiya pay half of the 5% fee (buichigin) conventionally paid by property sellers to the association and sought the approval of association constituents. Initially, the constituents rejected the administrator’s proposal. In order to avoid damaging the administrator’s reputation, however, they agreed to allow Shibushiya to transfer the property if he agreed to the following conditions. Namely, they requested that he pay half the 5% fee commonly provided by sellers and provide an equivalent amount in the form of a monetary gift (shoshūgi) to the association. Shibushiya agreed to the conditions and the transfer of ownership to Kanbē was recorded in the land register. In the eleventh month of Kanpō 3 (1743), however, the circumstances of Shibushiya’s case and a provision reconfirming the ban on the transfer of properties to employees (tedai) and other persons of low rank (komono) were added to the Register. Constituents then added their seals to the newly-added as confirmation. Furthermore, when the Register was renewed, the following statement was included: “The transfer of property to servants and relatives other than those mentioned in the Register relations is strictly prohibited.”

Although the document states that Shibushiya transferred his property to his Kanbē, he actually sold it to him. It is likely that he attempted to disguise the sale as a transfer in order to avoid paying the 5% buichigin fee. Ultimately, however, the members of the association were unwilling to agree to the transfer and a compromise was reached only after the neighborhood administrator intervened.

Regardless of how the matter was resolved, however, Shibushiya’s case indicates that association approval was, in fact, necessary when attempting to transfer or sell a property. Furthermore, this incident resulted in the reconfirmation of an existing association regulation regarding the sale of properties, and indicates that such regulations were, in fact, impactful.

Fees, such as the 5% buichigin mentioned above, as well as those paid by new constituents when formally joining an association (kaomisegin), entering the association office(kaishoiri 会所入), and feting other association members (furumaigin) were listed in a separate document referred to as the Block Association By-Laws, which was compiled at the same time as the Register of Rules and Agreements within the Block Association.

Articles thirteen through the twenty-seven detail constituents’ obligations to the association. Let us compare articles thirteen and fourteen. According to article thirteen, when a new administrator was appointed, all association members were obligated to provide him with a monetary gift and the cash equivalent of food and drinks. In addition, members were required were to fete the new administrator with food. Article fourteen stipulates that block association members should provide monetary gifts when a constituent married. However, it also mandates that the individual getting married provide food or a like amount in cash (furumairyōgin) to the other association constituents and administrator. Similar provisions can be found in articles concerning “the marriage of a son of an association member,” “when an association member adopts someone,” and “when a husband is taken in [as an adopted heir].” This indicates that association administrators were appointed at the request of association members. In contrast, the Register mandates that a party (hirome 披露目) should be held not only at the time of marriages and other celebrations, but also when a new constituent joined the association. Following these provisions are rules for caretakers, including their marriages, marriages of their sons, and adoptions. When the individual involved was a caretaker, the rates for celebratory gifts given by the association were less than half of those provided to landowning association members. These provisions indicate the place of caretakers within association. However, as caretakers paid cash instead hosting wedding celebrations (furumaigin)and money for the début of adopted children (kaomisegin), we can assume that they also received a portion of money paid by full-fledged association members (landowners), as well (See article twenty-five).

We should also pay attention to article twenty-one, which states that “when the servants of landowners living in other associations are adopted or marry, they should not be provided with celebratory gifts.” “Servants of landowners living in other associations” (tachōmochi no genin) probably refers to instances in which masters, such as the wealthy Mitsui family, placed servants as managers (tanashihainin 店支配人 ) of large shops in other associations. However, these managers were not on equal footing with other association constituents. It is thought that when the actual landowners living in other associations married and so on, they could request gifts. However, whether or not these absentee landowners could be involved in association administration varied from association to association. Certainly there were associations in which caretakers acted as representatives of absentee landowners by sealing documents in their stead. However, the Hōreki 11 (1761) Handbook of Regulations within the Association (Chōnai kiku chō 丁内規矩帳)*⁴ from Amagasaki chō 2-chōme, where there were many powerful moneylenders (ryōgaeshō), states: “Concerning the rules of this association: from long ago only constituents residing in the association have met – excluding landowners living in other chō and other provinces – and, considering the formalities from the past, have discussed various matters concerning our rules in order to prevent various occurrences and behaviors that cause disturbances.” In other words, the management of Amagasaki chō 2-chōme was restricted to only association members living within the boundaries of the association.

*4 Ōsaka no chō shikimoku, Ōsaka shishi shiryō 32.

In addition to the above, article twenty-two states that the association members were to treat the association administrator to a meal comprised of a main dish, soup, and two sides (ichijū sansai) when they gathered for the first time each year to seal the shūshi maki and in the tenth month when a new shūshi maki was composed. In addition, article twenty-three stipulates that those involved were to fete the administrator, monthly representatives, five-household association members, and association secretary when a property was sold or transferred. Additionally, when the association’s cadastral register was amended, gifts were to be provided to the district chief (sōdoshiyori) and other city officials. In addition, the association secretary was to receive a portion of the 5% fee (buichigin) provided to association members.

In the foregoing analysis, we have examined the contents of the Register of Rules and Agreements within the Block Association for Miike dōri 5-chōme. The existence of such rules and regulations tell us much about block association’s character and function. Furthermore, the detailed nature of the procedures governing entry into an association – as seen in the rules concerning the buying and selling of lots or the various provisions concerning parties to announce new members – can be described as an expression of the association’s organizational nature.