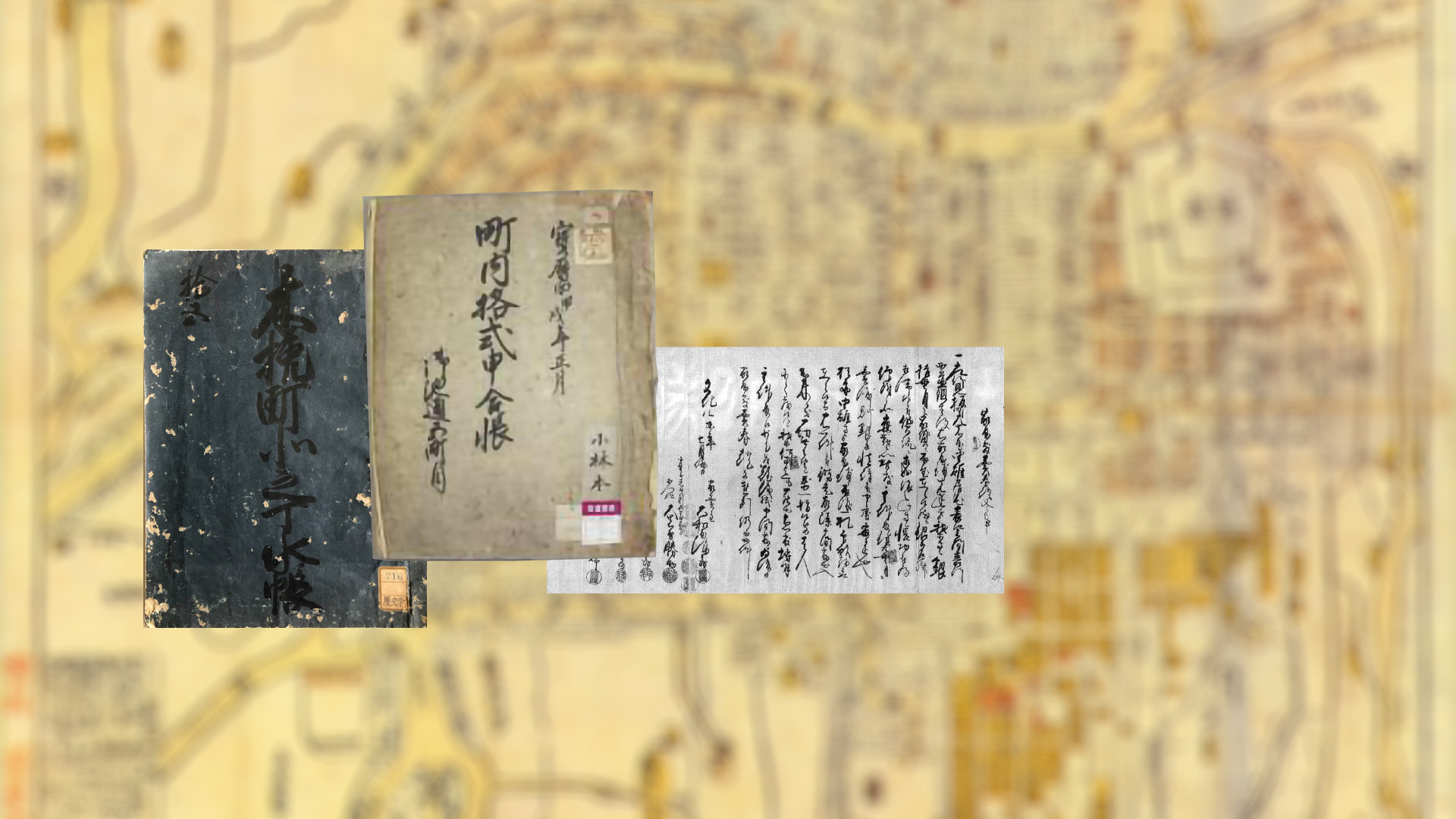

Hero Image:「改正懐宝大阪図」(大阪古地図集成第8図)より

※大阪市立図書館デジタルアーカイブをもとに加工

http://image.oml.city.osaka.lg.jp/archive/detail?cls=map&pkey=r1008001

During the previous nine lectures, we empirically analyzed the life world of early modern Osaka’s residents with a particular focus on the block association. As noted in the introduction, the city’s socio-economic structure was organized around the principle of status. Accordingly, persons of warrior status lived in warrior estates, while religious professionals resided on land under the authority of shrines and temples. Additionally, there were areas reserved for outcaste groups, such as Watanabe Village (also called Yakunin Village), where persons of kawata status lived, and the city’s four hinin enclaves.

Furthermore, an analysis of the economic activities of city residents reveals that merchants and artisans residing in Osaka’s commoner districts established a wide array of licensed occupational organizations (kabunakama), which exerted monopoly control over specific trades and livelihoods. Recent scholarship on such organizations includes studies focusing on Osaka’s association of sake brewers and a group of wholesalers selling materials used to produce medicines.*? Additional research has focused on organizations of brokers and wholesalers linked to the city’s dried fish and vegetable markets.*?

*1 Watanabe Sachiko, Kinsei Ōsaka yakushu no torihiki kōzō to shakai shūdan. Seibundō shuppan, 2006; Yahisa Kenji, “Kinsei Ōsaka sangō shuzō nakama no kōzō,” in Tsukada Takashi and Yoshida Nobuyuki, eds., Kinsei Ōsaka no toshi kūkan to shakai kōzō. Yamakawa shuppansha, 2001; Yahisa Kenji, “Kinsei Ōsaka no sake naka tsugi nakama to shuzō nakama,” Hisutoria 183, 2003.

*2 Hara Naofumi, “Ichiba to nakama,” Rekishigaku kenkyū 690, 1996; Hara Naofumi, “Matsumae ton’ya,” in Yoshida Nobuyuki, ed.,Kinsei no mibunteki shūen 4 akinai no ba to shakai. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2000; Hara Naofumi, “Hakodate sannbutsu kaisho to Ōsaka gyohi ichiba,” in Tsukada Takashi and Yoshida Nobuyuki, eds., Kinsei Ōsaka no toshi kūkan to shakai kōzō,Yamakawa shuppansha, 2001; Hara Naofumi, “Akinai ga musubu hitobito ? jūsō suru nakama to ichiba ? ,” in Mibunteki shūen to kinsei shakai 3 akinai ga musubu hitobito. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2007; Yagi Shigeru, “Kinsei Tenma aomono ichiba no kōzō to tenkai,” in Tsukada Takashi, ed., Ōsaka ni okeru toshi no hatten to kōzō. Yamakawa shuppan, 2004; Yagi Shigeru, “Aomono shōnin,” in Hara Naofumi, ed., Mibunteki shūen to kinsei shakai 3 akinai ga musubu hitobito. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2007.

Artisans also formed occupational associations. In large cities, the presence of warrior estates, shrines, temples, and large merchant houses, combined with demand for comparatively austere back-alley tenements ensured that carpentry guilds were the most common type of early modern occupational association. Carpentry organizations in Osaka, Kyoto, and the surrounding area (the Kinai) were governed by the Nakai House. Additionally, low-level assistant construction workers (tetsudai) resembling Edo’s tobi formed their own associations, which were placed under the authority of Shitennō Temple.

The same is true of unskilled laborers, such as stevedores (nakashi), who formed territorial organizations and associations based on client relationships (deiri kankei) with domainal storehouses. Storehouses depended upon the city’s stevedore associations in order to transport large amounts of cargo, such as tribute rice. Together with the servants employed by warrior households and domestic servants*? hired by merchant households, stevedores and assistant construction workers formed part of Osaka’s day-labor stratum, whose members survived by selling their labor power. The early modern urban lower class was comprised of two groups: rear tenants, who formed households (ie) and possessed a few assets, and unmarried day laborers, who lacked the economic wherewithal to form their own households. *?

*3 Translator’s note: Domestic servants (daidokorokata hōkōnin) were unskilled laborers who worked to maintain the merchant’s household.

*4 Yoshida Nobuyuki, “Nihon kinsei toshi kasōshakai no sonritsu kōzō,” Rekishigaku kenkyū, 534, 1984. Later republished in Yoshida Nobuyuki, Kinsei toshi shakai no mibun kōzō. Tōkyō daigaku shuppan kai, 1998.

In early modern Osaka, licensed occupational organizations, such as those mentioned above, were intimately intertwined with the city’s block associations and other urban social groups. In order to elucidate early modern Osaka’s actual structure, it is essential to examine these groups in relation with one another. For more on this, please refer to the articles included in the March 2012 special issue of City, Culture and Society, which focuses on urban Osaka’s history (CCS 3-1). *?

*5 The articles are:

1.Introduction The Urban History of Osaka (Takashi Tsukada)

2.Recovering Japan’s Urban Past: Yoshida Nobuyuki, Tsukada Takashi, and the Cities of theTokugawa period (Daniel Botsman)

3.The City of Osaka in the Medieval Period: Religion and the Transportation of Goods in the Uemachi Plateau (Hiroshi Niki)

4.The People Connected with Vegetable Markets (Shigeru Yagi)

5.Stevedores and Stevedores’ Guilds (Tōru Morishita)

6.Town Carpenters and Carpenters’ Groups in Osaka (Naoki Tani)

7.Construction Workers’ Guilds in Early Modern Osaka (Yoshiyuki Taketani)

8.The Traditional City of Osaka and Performers (Yutsuki Kanda)

9.The Hinin and City Neighborhoods of Nineteenth-Century Osaka (Takashi Tsukada)

10.Urban Lower-Class Society in Modern Osaka (Ashita Saga)

11.Poverty, Disease, and Urban Governance in Late Nineteenth-Century Osaka (John Porter)

12.Progressivism Personified: Urban Social Policymaking in Modern Osaka (Jeffrey Hanes)