Hero Image: 「改正増補国宝大阪全図」 (大阪古地図集成 第15図)より

※大阪市立図書館デジタルアーカイブをもとに加工

Osaka was divided into hundreds of self-governing block associations known as “chō,” which served as the basic unit of life in the early modern city. While the structure and character of these organizations varied from city to city, their basic character as a status organization comprised of commoners was universal. In the following paragraphs, let us examine the chō with a focus on its role as the basic unit of urban life.

Individual chō were divided into narrow residential lots commonly known as machiyashiki or, in the case of Osaka, ieyashiki. Most chō were structured in such a way that they included lots lining both sides of a shared street. Such chō are commonly referred to as ryōgawachō, or “dual-sided chō.” Generally, all of the lots in a given chō faced the street.

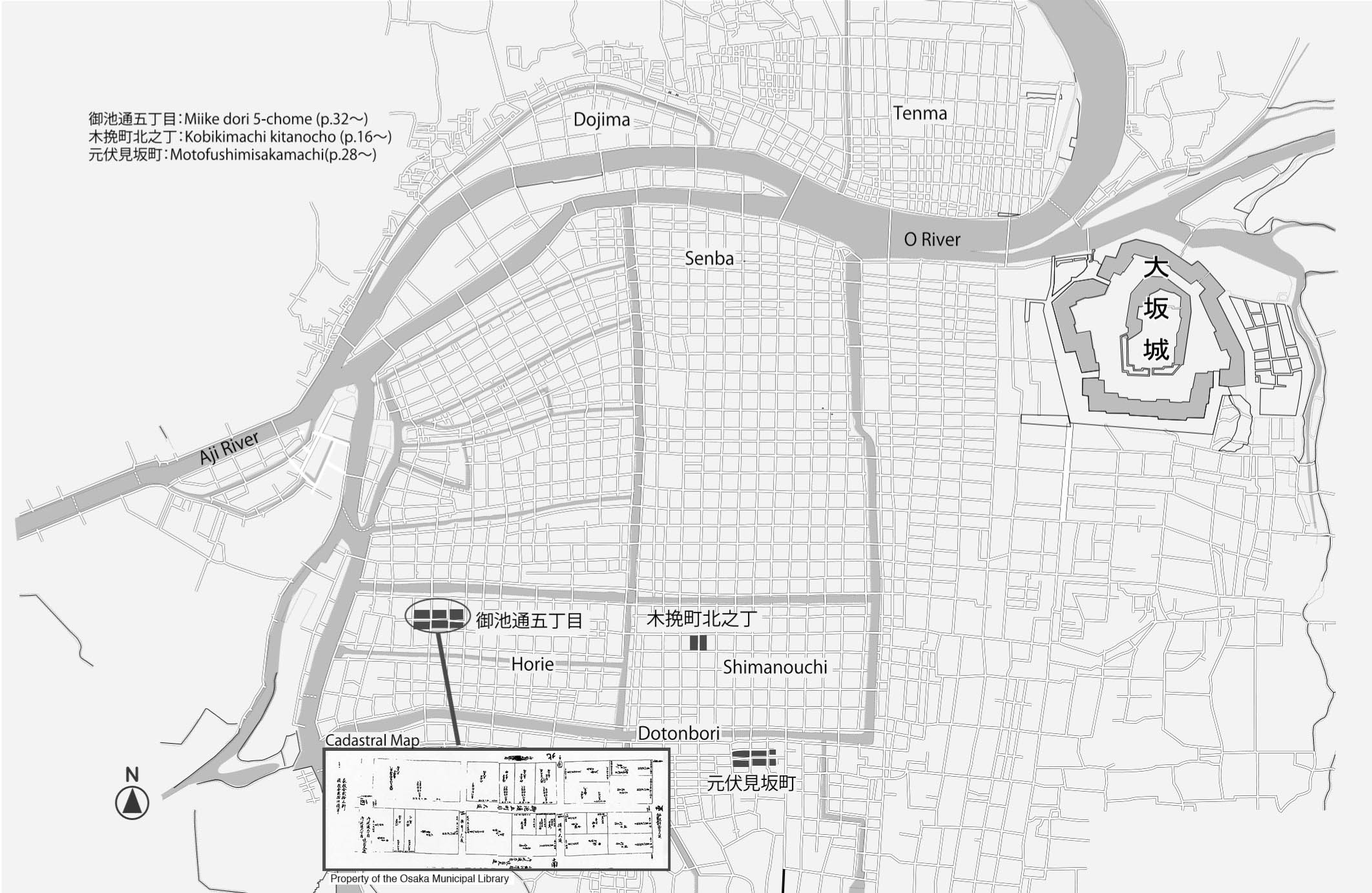

As we observed in the previous section, the city of Osaka was constructed according to a single, overarching vision. Rather, it was developed incrementally through the execution of a series of distinct urban plans. As a result, the city area was not organized according to a uniform pattern. Take, for example, the central part of Osaka’s Senba district, which was laid out in a relatively straightforward manner. The neighborhood’s streets ran north-to-south and east-to-west and it was divided into uniform 80-meter by 80-meter square blocks, which were arrayed in a chessboard-shaped grid.

Most of the residential lots in Senba were located along the neighborhood’s east-to-west-running streets. Generally, individual chō were comprised of the residential blocks on the eastern and western sides of a shared street. Most residential plots had a north-to-south depth of 40 meters. In other words, individual lots generally extended to the mid-point of the block in which they were located. Therefore, within each block, two sets of residential lots stood back to back, with one set extending north and the other extending south. A sewer ditch ran east-to-west between the two sets of opposite-facing residential plots. Such sewer ditches were known as sewari gesui, or “rear-partition sewers.” Because the Uemachi Plateau was located to the east, the coast was located to the west, and the land in the low-lying Senba area was western sloping, it was logical that the sewer ditches run east-to-west.

In Osaka, although individual chō were comprised of the residential lots on both sides of a shared street, a single chō generally extended one to three blocks. Although most chō spread out from east-to-west, some extended north-to-south. Individuals who owned residential lots in Osaka’s chō were known as iemochi. As the only formal constituents of the chō, these individuals can be classified as chōnin, or people of the chō. Therefore, chō can be defined as territorial organizations of local landowners, or chōnin. In addition, the term ieyashiki refers not only to the buildings on a residential lot but also to the lot itself. While there were many cases in which a single housing unit occupied an entire lot, there were also cases in which multiple dwellings shared individual lots. In addition, landowners commonly used residential lots not only as the location for their homes and shops, but also as a site for rental housing.

As the foregoing description indicates, ownership of a residential lot in a specific chō rendered one a constituent or member of that chō. It also served as the standard by which various taxes were levied by the Bakufu and chō on individual landowners. Namely, taxes of various types were levied in accordance with the quantity, area, and frontage of the lots within a given chō. In addition, as a communal organization, the chō functioned to protect the assets and livelihoods of individual constituents. The chō served as the basic mechanism through which the Bakufu exercised rule over city residents. In addition, chō constituents were forced to assume collective responsibility for the actions of their neighbors. Therefore, all sales of residential lots had to be approved by the chō. Also, it was essential that both the chō and the Bakufu knew the identity of the constituents of each chō.

Let us now examine the structure and administration of the chō organization. In each chō, there was a local administrator known as the chōdoshiyori. The administrator served as the representative of chō constituents and played a central role in the chō’s administration. In Osaka, administrators were frequently selected through a balloting process. However, that process did not amount to a direct election. Rather, after chō constituents had nominated two or three candidates, the candidates’ names were submitted to the district office, where the district chiefs made the final selection.

Two monthly representatives, or gachigyōji, assisted the headman. Monthly representative was an alternating position performed each month by two local landowners. Therefore, landowners were expected to perform a range of duties for the chō, including serving as monthly representative. In addition, they held the right to cast votes when new administrators were selected. Notably, even if alandowner actually lived outside of the chō, he had a responsibility to perform the above duties and exercise his rights as a constituent of the chō. Accordingly, when the landowner in question lived in another chō or domain, a caretaker known as a yamori was appointed to look after the landowner’s property. In place of the landowner, the caretaker collected rent payments from the landowner’s tenants, managed the landowner’s rental housing, and fulfilled the landowner’s obligations to the chō. This included periodically serving as monthly representative in place of the landowner.

Chō residents formed five-household associations, or goningumi, with their neighbors. In the case of properties that were owned by an absentee landowner and managed by a caretaker, the caretaker, of course, assumed the place of the landowner in the five-household association. When a residential lot was sold or used as collateral for a loan, the members of the landowner’s five-household association were required to jointly seal the contract.

Each chō also employed functionaries known as chōdai, who performed various tasks in exchange for a monthly wage. In the eighteenth century, chōdai began to perform a range of duties originally executed by chō administrator and monthly representatives. As chōdai became increasingly encumbered with duties, many chō also began to employ menials (shitayaku) and night watchmen (yabannin). In addition, many chō employed hinin guards called kaitoban.

In Osaka, each chō had a small administrative office known as a chōkaisho, which served as the center of chō administration. In many cases, the chōkaisho was constructed on a lot known as the kaisho yashiki, which was the collective property of the chō.

The population of most chō also included a large numbers of renter or tenants known as kashiyanin. However, renters were not considered official constituents of the chō and fell under the authority of the landowner on whose property they lived. Accordingly, they were almost entirely excluded from the local administration of the chō.

Below, we will analyze a series of documents, including a neighborhood land register (mizuchō) and a residential sales contract (baikenjō), in order to elucidate the spatial structure of the early modern chō. Also, in an effort to clarify the chō’s organizational and administrative structure, we will examine a set of internal regulations formulated by the constituents of a specific chō. The early modern chō’s character as a self-governing body is most clearly expressed in the fact that independent land registers were produced for each chō and that individual chō had autonomous sets of internal regulations.