This paper is a result of “Marginal Social Groups’ Experiences of Modernity: Building Bridges between Historians of Asia in Japan and the West” (2017-2019; representative: Takashi Tsukada), a project of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. It was published in Shidai Nihonshi 21 (The Historical Journal of Japan by Osaka City University, 2018). It will be posted here in two parts.

https://dlisv03.media.osaka-cu.ac.jp/il/meta_pub/G0000438repository_13484508-21-74

Introduction: Postwar Document Surveys

The society of early modern Japan left behind an enormous amount of village and town-level historical documents, and can be said to be a rare case in world history. Moreover, this documentation was not limited to that from rural villages and city wards, as we also have extensive documentation from various other social groups. My own research has examined the hinin (beggars) status group, who formed organizations within the city of Osaka known as the four kaito nakama, and left behind a rich documentation of their organization, despite being targets of poor relief. This has often surprised other scholars at international conferences in Europe and Asia organized around the theme of poor relief, as they have only seen beggars appear in historical documents as objects of official concern, and never leaving behind documentation of their own.

The presence of this rich documentation is closely connected to the unique social makeup of early modern Japan. The establishment of the bakuhan system[1] from the late sixteenth to the early seventeenth century was inextricably linked to the formation of “traditional” rural society based on the village and household unit; this basis of traditional society held social significance up until the period of high economic growth in the second half of the twentieth century. At the same time, early modern Japan was also an era of urbanization, as it saw the emergence of numerous castle towns across the entire country, each with a population ranging between 10,000 to 100,000 people, along with the so-called “three metropolises” of Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto. In all of these cities, the basic unit of daily life for urban residents was the chō, a social group composed of all property-holders in a given city ward, which was made up of all residential plots in a two-block area. Beneath the shogunate and daimyo, official rights and political power was dispersed amongst these various villages and chō, who produced a vast archive of documents that has been preserved to this day.[2]

Now, it should be said that the historical profession in Japan did not begin to grapple with these village and town level documents until after the end of the Second World War. Although there were pioneering studies using such documents conducted in the prewar era, within a prewar historiography dominated by political and diplomatic history, it was the documents of the ruling class, such as shogunal and daimyo lords, that enjoyed pride of place.

After the end of the war, many feared the total loss of village documents, as many old houses who could trace their lineage back to the early modern period were facing a crisis due to the postwar land reforms. Thus, from 1946 on the Committee for the Survey of Documents on the History of the Land System, (part of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry) and the Committee for the Survey of Documents from Farming and Fishing Villages (part of the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science) initiated efforts to survey and collect historical documents. From 1948 on, the Committee for Surveying Early Modern Documents Related to People’s History (a special committee of the Science Council of Japan) began a five year survey of documents from across Japan, and in 1951 the Archives of the Ministry of Culture (now part of the National Institute of Japanese Literature) was established. Additionally, a new generation of younger historians had awakened to the importance of studying history from the perspective of the ruled, and many visited established households in rural villages to survey their household documents. What emerged was a wealth of new historical research based on these documents.

All of this activity raised the awareness of historians to the importance of these kinds of documents, and formed the basis of the document surveys and document preservation that continues to this day. However, these earlier document surveys had their limitations, in that they paid little heed to the original conditions in which historical documents had been preserved. From the 1970s and 80s on, there were growing calls to conduct document surveys based on methods that realized the importance of recording and archiving documents based on the conditions in which they were discovered.[3] In recent years, the Japanese history department at Osaka City University has conducted over twenty comprehensive historical surveys in the Izumi City region with the cooperation of Izumi City. Below, I will discuss the experience of this comprehensive research survey while highlighting our survey methods, which give great attention to the original state of historical documents.

Section One: Village and Town Level Documents

The existence of rich documentation from the village and town levels presupposes the creation of large volumes of documents. To elaborate on this point, I will discuss some examples from my recent work.

1. Village Documents

During the early modern period, there were close to 60,000 peasant villages across Japan, which formed the basic unit for rural society. Although the shape of these villages could vary by location, we can take the basic form to be a community composed of tens of households, with an annual estimated yield of between 300 to 400 koku.[4] These villages were self-governing communities formed around a core of households who acted as the village leadership (headman and village elders), and who assumed responsibility for collecting the village tax obligation for the lord of the village.

During the early modern period, there were close to 60,000 peasant villages across Japan, which formed the basic unit for rural society. Although the shape of these villages could vary by location, we can take the basic form to be a community composed of tens of households, with an annual estimated yield of between 300 to 400 koku.[4] These villages were self-governing communities formed around a core of households who acted as the village leadership (headman and village elders), and who assumed responsibility for collecting the village tax obligation for the lord of the village.

The Taikō Kenchi,[5] which created the basis for the early modern village, confirmed the land holdings of individual peasant households, yet also produced survey records for each village that not only recorded the land holdings of each household, but also list the village’s estimated annual yield. Registers of religious affiliation,[6] created every year, hold great significance for calculating population in each village. According to the village-receivership system, every autumn, the lord’s officials would send the village leadership (consisting of the headman, village elders, and smallholder’s representative) a document (nengu menjō) listing that year’s tax burden. The tax burden would then be divided up within the village amongst the various individual households, producing records called the menwari chō. After the village delivered their tax burden up to the lord, he would provide a document confirming the payment in full (kaisai mokuroku), which concluding the entire process. Various documents related to petitions were also created, and we have collections known as goyō-tome which catalog such petitions, as well as various directives issued from the lords. Finally, documents recording the sale or pawning of land between individuals also required the seal of the village leadership, and thus were also preserved.

Within these early modern villages, a great variety of documents were created and preserved by the village headman. Within early modern society, which made no distinction between the “public” and “private,” official village documents were preserved alongside the household documents of the headman in question. Yet there were occasions when the position of village headman transferred to another family, and on such occasions, we can see that both parties distinguished between the village’s documents and the personal household documents of the former headman.

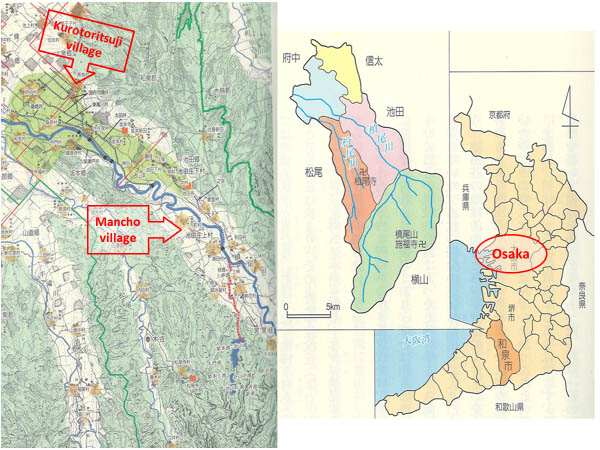

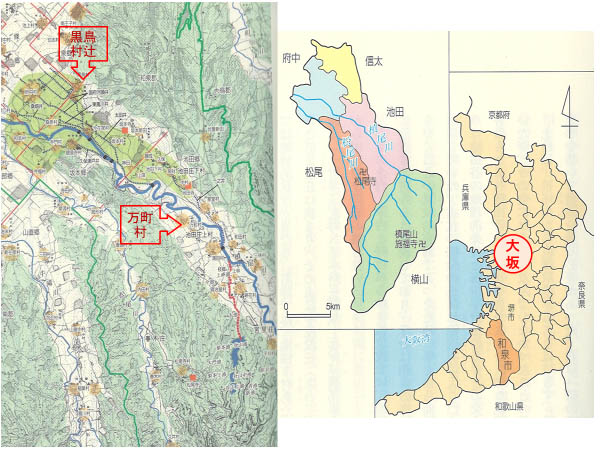

Kurotoritsuji Village[7] – In Kurotoritsuji Village of Izumi County, Izumi Province (today’s Izumi City), an intra-village dispute occurred between 1696-7, resulting in the force retirement of the Tarōemon household, who had served as village headman since the beginning of the early modern period. From 1697 until 1705, the Jindayū household became village headman. Friction arose between the new and old headmen over the handling of the village’s land register, and we can confirm that this register was passed on to the Jindayū household in 1715 from an official letter of receipt (uketorisho) sent by Jindayū to Tarōemon. This letter of receipt mentions part of the document being transferred from one household to the other, but also includes much information about land taxes, as well as a settlement describing the resolution of the intra-village dispute. After this, in 1732, the position of headman passed to the Kurokawa Bu’emon family, and so the official village documents changed hands once again. From the mid-eighteenth century until the early nineteenth century, the Kurokawa family wielded an overwhelming amount of political and economic power within the village. However, a series of unpaid debts, along with loans given to the daimyo, ruined the Kurokawa family. This led to a change in the position of headman, which was assumed by the Asai Ichi’emon family in 1822.

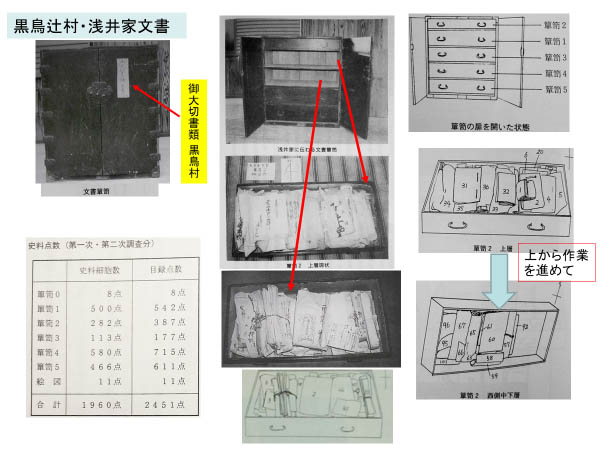

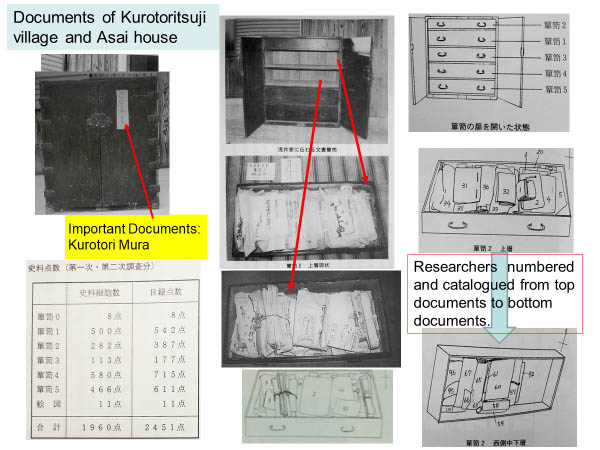

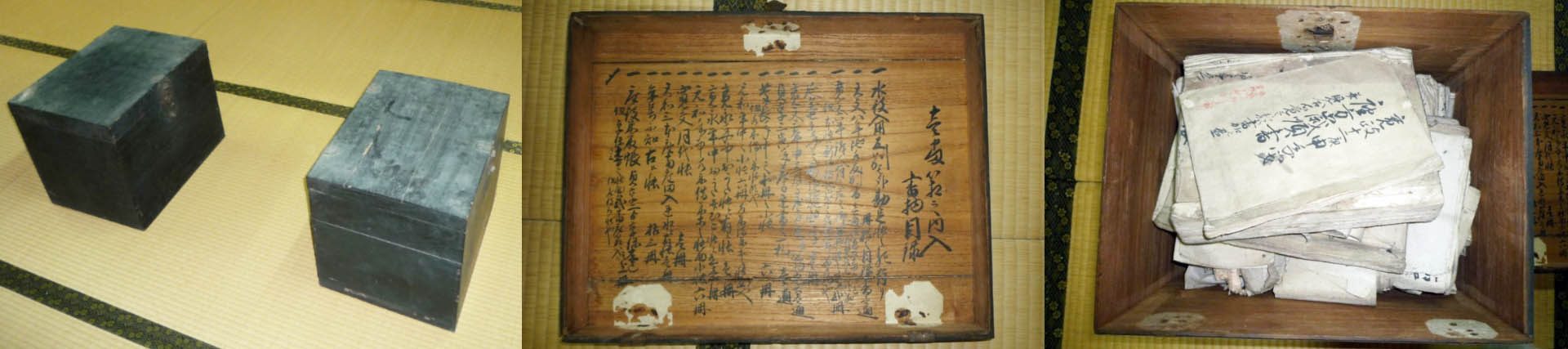

The Izumi City History archival activities began in 1997, but the basis of this were surveys of the documents of Kurotori Village conducted by a group of early modernists starting in 1994, centered around myself. For this survey, we visited the heir of the Asai House (currently the Takeuji Family), which had served as village headman of Kurotoritsuji since 1822. We asked to see the family documents, and discovered a storage chest of documents kept in the family warehouse. On the outside of the storage chest was a seal reading “Important Documents Kurotori Village.” As we can see, this reveals an awareness that the documents were not simply the personal items of the Asai household, but were in fact important documents of “Kurotori Village.” Within the chest were five drawers. We gave each a number and catalogued all the documents, which totaled 2,451 items.

Each drawer contained numerous documents, which were organized and placed into different envelopes. For example, in the envelope for 1778 we have a document titled “Regarding the Loan to the Sakai City Magistrate\Izumi Province, Izumi County, Kurotori Village\Headman Kurokawa Bu’emon (2 – 55); or from 1776 “Loan Agreement for Kōji Purchase” (2 – 16 – 3 – 1); from 1797 “Collective Management of Kyōkyōsu Weir, Kurotori Village\Kannonji Village Dispute Over Weir” (2 – 12). All of these documents were collected during the Kurokawa Bue’mon family’s tenure as village headman, and were then passed to the Asai family. Also within the Asai family collection are several documents that were produced during the tenure of earlier headmen like the Tarōemon household of the seventeenth century, and the Jindayū household of the early eighteenth century. From this, we can see that when the post of village headman changed hands, so too did the official village documents. However, this document exchange was by no means a natural, established system; rather, we must pay attention to the fact that the exchanges only occurred due to intra-village disputes and severe tensions between the old and new headmen.

Manchō Village[8] – Manchō Village, also located in Izumi county, Izumi province, is well-known as the site where the Kokugaku scholar Keichū resided when he conducted his work on the Manyoshu. Supporting Keichū, however, was the Manchō Village headman, Fuseya Chōzaemon Shigekata. The Fuseya household held a great degree of economic power in the region, and not only served as the successive headmen of Manchō Village, but also acted in roles like village-group headman over a number of neighboring communities, making them the most powerful family in the area. Fuseya Shigekata, who allowed Keichū to reside in his personal residence, was a central member of a group of Izumi poetry enthusiasts based in Sakai City, and personally left behind a remarkable record of cultural activities and accomplishments in his own right.

Three generations later, the head of the Fuseya household was an individual named Fuseya Chōzaemon Masayoshi, who from the late eighteen to the early nineteenth century penned two volumes of a history of Manchō Village and the Fuseya Household called the “Zokuyūroku.” This project was continued by Masayoshi’s son (Chōzaemon Yoshikusu) and grandson (Chōzaemon Isoyoshi), who continued work on the third volume of the “Zokuyūroku” well into the late Edo period. The record contained in “Zokuyūroku” stretches from 1523 until 1862. After the Meiji Restoration, the Fuseya household left Manchō Village, and any documents they left behind have been lost. However, the “Zokuyūroku” was compiled based on household documents of the Fuseya, as well as Manchō Village material that had been edited and complied by Masayoshi and his successors. The documents from which the narrative of the “Zokuyūroku” was constructed reveal the rich archive that existed for the Fuseya household.

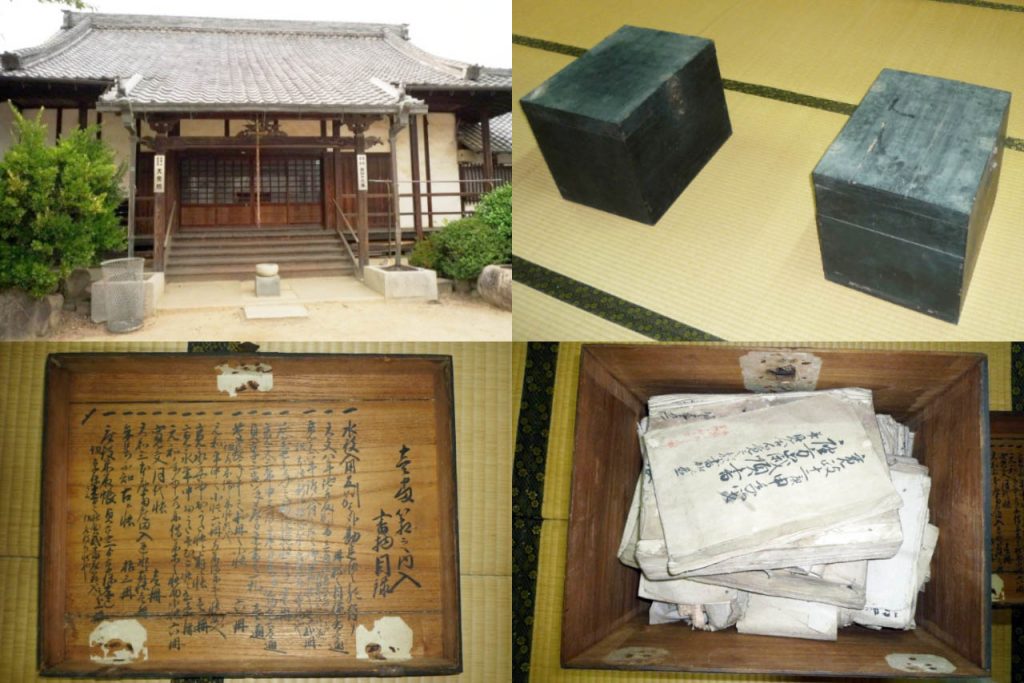

For example, there is a record of a decision made in 1686 to combine the village’s shrine organizations, of which there had been two up to that point. The “Zokuyūroku” also lists how in 1800, the abundance of shrine organization documents necessitated the creation of an additional storage container. This event shows us that there was one container for important documents kept under lock and key in the storehouse, while a second chest held those documents that were referred to more often. This shows us that Masayoshi did not just rely on Fuseya household documents to write the “Zokuyūroku,” but also drew from such village documents as those related to the village shrine organization.

In June of 2017, a survey was conducted of the Buddha statues in Kōbōji and Tenjuin temples. On June 11th, two wooden chests were discovered on a shelf in Tenjuin. These were precisely the same chests that, according to the “Zokuyūroku,” were created in 1800. Within were many items, including documents from the seventeenth century, but also a document labeled “Kansei 12 Shrine Organization Records and Regulations.” This document was produced for daily reference out of older material when the shrine organization documents were reorganized, and the older materials were stored in one locked chest. Here, the record of the consolidation of the village lay-organization from 1686 has virtually the same content as that recorded in the “Zokuyūroku.” In all likelihood, it was Fuseya Chōzaemon Masayoshi who created this document label from 1800. This cataloging of shrine organization documents thus contributed to the compilation of the “Zokuyūroku.”

In today’s Manchō, though phrases like “junnin shū” (the ranked members of the shrine organization) are still remembered by older residents, the shrine organization itself has ceased to function.[9] It is for this reason that, in recent years, the shrine organization documents were stored away on a shelf in Tenshuin. However, even after the end of the early modern village and the departure of the Fuseya family from the village, the shrine organization continued to function and pass on its documents. A survey of the documents contained in this box has yet to be conducted. There is a plan to conduct an investigation during the 21st collaborative research survey in September of 2017.[10]

In summary, the examples of Kurotori and Manchō villages of Izumi City provide a concrete example of the great quantity of documents produced in early modern villages and preserved till this day.

2. Town Level Documents

Early modern Osaka was divided into three districts (kita-gumi, minami-gumi, and tenma-gumi), which until the mid-eighteenth century were composed of 620 chō (neighborhood; city ward).[11] Chō of the Edo period differed from the city-wards of contemporary cities, in that they were cooperative social groups composed of all property-holding residents; as the basic unit of daily life for city residents, chō occupied an important position. To be a property owner (ie-mochi) meant owning a residential lot within the chō, which were composed of lots lining both sides of a shared street. Many tenants who rented property also lived in the chō, but they were not considered to be official members of the chō as social group. The chō administration was centered on a headman (chōdoshiyori), who acted as representative of the chō, and also included two property-owners who served on a rotating basis. However, it was relatively common for actual administration of the chō to be handled by an individual hired by the chō, known as a chō-dai. Most chō possessed a space for meetings and administration known as a kaichō.

Land registers known as mizu-chō were created by each chō. The chō were also responsible for creating annual registers of religious affiliation (shūmon ninbetsu-chō) just like the rural villages, as well as monthly documents known as shūshi-maki, wherein the chō members confirmed there were no Christians, gambling, or sale of prostitutes within the chō. The chō created numerous other documents, including copies of town edicts (machi-fure) and letters of guarantee issued in response; various petitions; and lawsuits, all of which were recorded in the official records of the chō, just as in the villages. Finally, the chō also preserved various internal documents, such as regulations for chō management and shared agreements among its members.

Among the regulations of the chō were provisions regarding the management of chō documents. Let us begin our discussion from there.

Amagasakimachi 2-chōme Amagasakimachi 2-chōme was a prosperous area administered by moneylenders, located on the west side of the Kita-Senba region of Osaka. In the ninth lunar month of 1761, the then-headman Aramonoya Rokuzaemon, monthly representatives Hizenya Uhei and Matsuya Bunkichi, along with chō resident Tsuruikeya Matashirō and eleven others, decided upon a list of chō regulations after consulting together.[12] Those property owners who were from outside of Osaka, or who lived in other areas of Osaka, were not included in this negotiation, nor were their representatives. The administration of Amagasakimachi 2-chōme was handled by property owners who resided within the chō, though this was by no means the case in other chō.

According to the list of regulations, the chō documents were to be divided into two groups in the following manner:

Group One:

[New Shūshi-maki] [Population Registers of Owners and Renters] [Land Registers and chō Map] [Old Shūshi-maki] [Parish Temple Seals] [Registers of Religious Affiliation] [Letters of Guarantee Among Relatives] [Various Matters Related to the Change of Headmen] [Documents Related to Road Maintenance] [Town Edicts Related to the Arrival of the Korean Embassies] [Expense Registers Related to Arrival of Shogunal Elders (rōjū)] [Register of Town Edicts Affixed with the Seals of Chō Residents] [Records of Property Sales and Mortgaged Properties] [All Documents Related to the Chō Bridge]

On these documents was a label that read “As these are all very important documents, during emergencies they shall be sealed away, while normally they shall be kept in the chō administrative office under the management of the headman and the chō-dai.” There was also an addendum stating that, in the event of fire, the chō-dai was to immediately drop whatever he was doing and escape with the container of documents.

Group Two:

[Chō Expenditures] [Rotation of Gatsugyōj] [List of Chō Regulations] [Financial Matters] [Regulations for Chō-dai Conduct] [Copies of the Land Register and Chō Map]

These documents of group two were labeled “These documents are to be kept by the gatsugyōji. When the seals are affixed to the shūshi-maki on the sixth of each month, the gatsugyōji of the subsequent month will receive them upon examining the documents.”

The first group were those important documents given highest priority when it came to preservation, and so were placed in a container so that they might always be ready for transportation. This was the responsibility of the chō headman and chōdai. While these were important documents, they were also not necessarily used on a daily basis.

The second group were those documents passed from one gatsugyōji to the next each month; in other words, these were documents necessary to the daily administration of the chō. The land register and chō map were essential to the management of the chō property, and so the originals were kept in storage along with the rest of the Group One documents, while copies were used for day-to-day administration.

From these regulations, we can see what kind of documents were created within Amagasakimachi 2-chōme, and how the documents were administered.

Dōshōmachi 3-chōme All members of the medicinal trade organization (an organization with 124 stock holders) were to live in three city wards (Dōshōmachi 1-3 chōme) according to the organization’s internal regulations, making Dōshōmachi 3-chōme a chō that was home to many individuals engaged in selling medicinal goods. In the intercalary eighth month of 1824, Kamiya Chūsuke, the headman of Dōshōmachi 3-chōme, along with twenty-five property owners (including four yamori, representatives of absentee landlords) created a list of regulations with thirty-seven items for administering the internal affairs of the chō. The last item reads as follows:

“Item: The various internal documents of the chō, as well as such things as the

furniture in the administrative office, are to be recorded on this register, and the

register is to be kept by the nenban.”

In other words, much of the internal documents of the chō were preserved in the administrative office, and were recorded – along with various pieces of furniture – on a register. We can also see that this register was handled by the nenban, a chō position responsible for the year’s accounting. While there is no list or register of chō documents in Dōshōmachi 3-chōme similar to that in Amagasakimachi 2-chōme, the minute administration of documents in the chō administrative office was one characteristic they both shared.

Today, the documents of Dōshōmachi 3-chōme are preserved in large quantities in the archives of the Osaka Prefectural Nakanoshima Library. This collection includes registers of religious affiliation and shūshi-maki from the mid-seventeenth century on, as well as numerous town edicts and documents related to goyō-yado (billeting of samurai officials). These items have been preserved in accordance with the system by which they were administered by the chō.

As we can see from the examples of the internal regulations of Amagasakimachi 2-chōme and Dōshōmachi 3-chōme, the chō of Osaka were communal organizations, self-administered by the constituent members of the chō; the basis of this self-administration were the chō ordinances and gatherings of chō members. These members had collective ownership of the chō administrative office, wherein the many documents and registers created in the chō were managed and preserved. Here we can see the unique social characteristics of the Edo period which produced a wealth of historical documents.

[Supplemental: The Kaito of Dōtonbori] One of my central research concerns has been the structure and historical development of the hinin (beggar) confraternities of early modern Osaka. In Osaka, the residences of these hinin groups (kaito) were clustered in four locations – Tennōji, Tobita, Dōtonbori, and Tenma – each of which constituted an independent hinin confraternity (kaito nakama). Regarding the Tennōji confraternity, a great many of the documents created by the successive headman (chōri) of the confraternity survive to this day.[13] Additionally, we have three volumes of documents related to the Dōtonbori confraternity, which were preserved as part of the household documents of the Ujihara Family of Namba Village, in whose territory the Dōtonbori hinin resided. These three volumes contain the successive documents of the Nariwai Family, who served as the headman of the Dōtonbori hinin from the early Edo period on.[14] The documents of the Nariwai family were deposited in the archives of the Osaka castle museum, and were photographed and surveyed by members of the early modern Osaka research group.

In Namba village, a great quantity of documents was collected from the beginning of the early modern period on. Interestingly, however, many of these documents were catalogued towards the end of the early modern period, leaving us several volumes of collected documents organized chronologically, with titles such as “Matters Related to the Hinin Confraternity,” “Matters Related to the Hairdressers Organization,” and “Matters Related to the Jōdō-sect temple Hōzenji.” From this, we can understand that a great number of documents were created and preserved in Namba Village. Even more surprising, however, is the high level of archival technique and historical consciousness displayed by the Namba village headmen of the late Edo period, who cataloged all of these village documents.

Included within the “Matters Related to the Hinin Confraternity” volume are many items called from documents sent from the headmen or bosses of the Dōtonbori confraternity to the headmen of Namba village, or documents issued from the confraternity to shogunal officials which required the seal of the Namba village headman. Here, we can see just how many documents were created by the early modern hinin confraternities.

End note

[1] Translator’s note: The “bakuhan system” refers to a system where political power was held by the Tokugawa shogunate as well as various daimyo domains. The latter were subordinate to the shogunate yet nevertheless enjoyed considerable autonomy in their own internal affairs.

[2] In the author’s view, early modern Japanese society was composed of a variety of officially recognized social groups, which included not only territorially-bounded groups like the villages and chō, but also the samurai households of the ruling class, as well as various artisanal guilds, merchant organizations, religious groups, hinin beggars, and more. I understand social relations among these groups in terms of “layers” (social relations between groups of the same status, e.g. peasant villages), and “combinations” (relations between groups of different status, e.g. peasant and outcaste villages). I developed this approach from the 1980s on as part of collaborative research on the research of status and marginalities in early modern society. See Tsukada Takashi, Kinsei mibun shakai no toraekata: Yamakawa Shuppansha kōkō Nihonshi kyōkasho o tōshite (Kyoto: Buraku Mondai Kenkyūjo, 2010).

[3] See Yoshida Nobuyuki’s discussion of this issue in Yoshida Nobuyuki, Chiikishi no hōhō to jissen (Tokyo: Azekura Shobō, 2015), especially Section III: Genjō Kiroku-ron.

[4] Translator’s note: one koku was roughly equal to 180 liters of rice, and was said to be the amount necessary to feed an adult man for one year.

[5] Translator’s note: the Taikō Kenchi was a massive land survey ordered by the warrior hegemon Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1594. This project not only surveyed the estimated yield of peasant villages, but also broke up the larger “fortified villages” (sōson) that had developed during the Warring States period into smaller communities. These smaller communities became the “village-receivership system villages” (muraukesei mura) typical of the early modern period.

[6] Translator’s note: Shūmon ninbetsu aratame chō provided the Buddhist temple registry for each household in the village, and typically listed the name, age, and gender of all members of each household. These lists were first ordered in the mid-seventeenth century as a measure to suppress Christianity.

[7] For the history of Kurotoritsuji Village, see Machida Tetsu, Kinsei Kurotori-mura no chiiki shakai kōzō (Izumishi-shi kiyō Dai 4-shū, 1999) and Tsukada Takashi, ed., Kyū-Izumi-gun Kurotori-mura kanei komonjo chōsa hōkokusho, Vol.2, Genjō kiroku no hōhō ni yoru (Izumishi-shi kiyō Dai 1 shū, 1997)

[8] For more information on Fuseya Chōzaemon and the “Zokuyūroku,” see Machida Tetsu, ed., Izumi-gun Manchō-mura kyūki: “Zokuyūroku” (Izumishi-shi Kiy, Dai 15 shū) (2008) and Hada Shinya, “Kinsei no Manchō-mura to Fuseya Chōzaemon-ke: Zokuyūroku o daizai toshite,” in Izumi chūō kyūryō ni okeru mura no rekishi, Izumishi-shi kiyō 16, 2009.

[9] Village shrine associations operated widely across the villages of Izumi, and a group of elders held the central position within these associations. The number of these elders differed from village to village, and their group would sometimes be called “the six-man group” or “the ten-man group.” In Manchō Village the number of elders was between one and three, and was called the “junnin shū.”

[10] The 2017 survey was conducted from September 20th to the 22nd, and we started an examination of the contents of this document container in October of the same year.

[11] For more on early modern Osaka see Tsukada Takashi, Rekishi no naka no Ōsaka (Iwanami Shoten, 2002).

[12] These are contained in Ōsaka no chō shikimoku, Ōsakashi shiryō Dai 32-shū, 1991.

[13] For more on the Tennōji kaito, see Tsukada Takashi, Ōsaka no hinin: Kojiki, Shitennōji, Korobi Kirishitan (Chikuma Shinsho, 2013).

[14] These are contained in Uchida Kusuo and Okamoto Ryōichi, Dōtonbori hinin kankei monjo (Jō, Ka, Seibundō Shuppan, 1974-76).

日本近世には、在方の基礎単位をなす村が六万近く存在していた。地域により存在形態は多様であったが、おおよその目安としては、家数数十軒、村高3〜400石というところであろう。これらの村は庄屋・年寄らの村役人を中心に自律的に運営され、領主支配の下で年貢の村請制を機能させていた。

日本近世には、在方の基礎単位をなす村が六万近く存在していた。地域により存在形態は多様であったが、おおよその目安としては、家数数十軒、村高3〜400石というところであろう。これらの村は庄屋・年寄らの村役人を中心に自律的に運営され、領主支配の下で年貢の村請制を機能させていた。