Osaka’s Formation and Development

Early modern Osaka’s development began in 1583 with Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s construction of Osaka Castle and the urbanization of the surrounding area. The Castle was constructed on the former site of Osaka Hongan Temple, a Buddhist institution that violently resisted the first of early modern Japan’s three great unifiers, Oda Nobunaga, for 11 years. The initial plan for Osaka’s development called for the construction of a linear city area on top of the Uemachi Plateau, which extended southward from the Castle area to the established urban settlements surrounding Shitennō Temple. The castle’s inner keep (honmaru) and outer keep (ninomaru), and the urbanized settlement surrounding it were located inside of a broad external barrier known as the sōgamae. In other words, the Castle was initially encircled by three lines of defense. Shortly before his death in 1598, however, Hideyoshi ordered the construction of a third keep inside of the sōgamae in order to ensure the safety of his young heir, Hideyori. As a result, commoners living on land within the area designated for the third keep were forced to relocate. In order to secure a suitable relocation site and sufficient residential space to house the vast pool of labor power required to construct the third keep, efforts began to construct residential settlements in the Senba area, which was located west of the Higashiyoko Canal. With the development of the Senba area, the plan for Osaka’s construction shifted from its north-south axis to include districts that extended westward from the Castle.

Since the sixth century, urban development in the Osaka region had been concentrated almost entirely on the Uemachi Plateau. With the development of the Senba area, however, the city area began to extend into the low-lying swamplands west of the Uemachi Plateau.

Formerly below sea level, the area west of the Uemachi Plateau was gradually reclaimed using sediment carried inland by the ocean current. Over time, areas previously under water transformed into marshland with extremely poor natural drainage. In order to prepare that marshland for urban development and ensure proper drainage, it was necessary to construct a series of canals. The earth that was taken out of the ground during the construction process was used to reinforce the land surrounding the canals. Residential housing was then constructed on the reinforced tracts of canal-side land.

During the Battle of Osaka in 1614 and 1615, Osaka Castle was destroyed and portions of the city were badly damaged. After assuming direct control of Osaka in 1619, Tokugawa Ieyasu initiated efforts to reconstruct the Castle and surrounding city. Thereafter, urban development continued apace in the city until about 1630, when construction slowed.

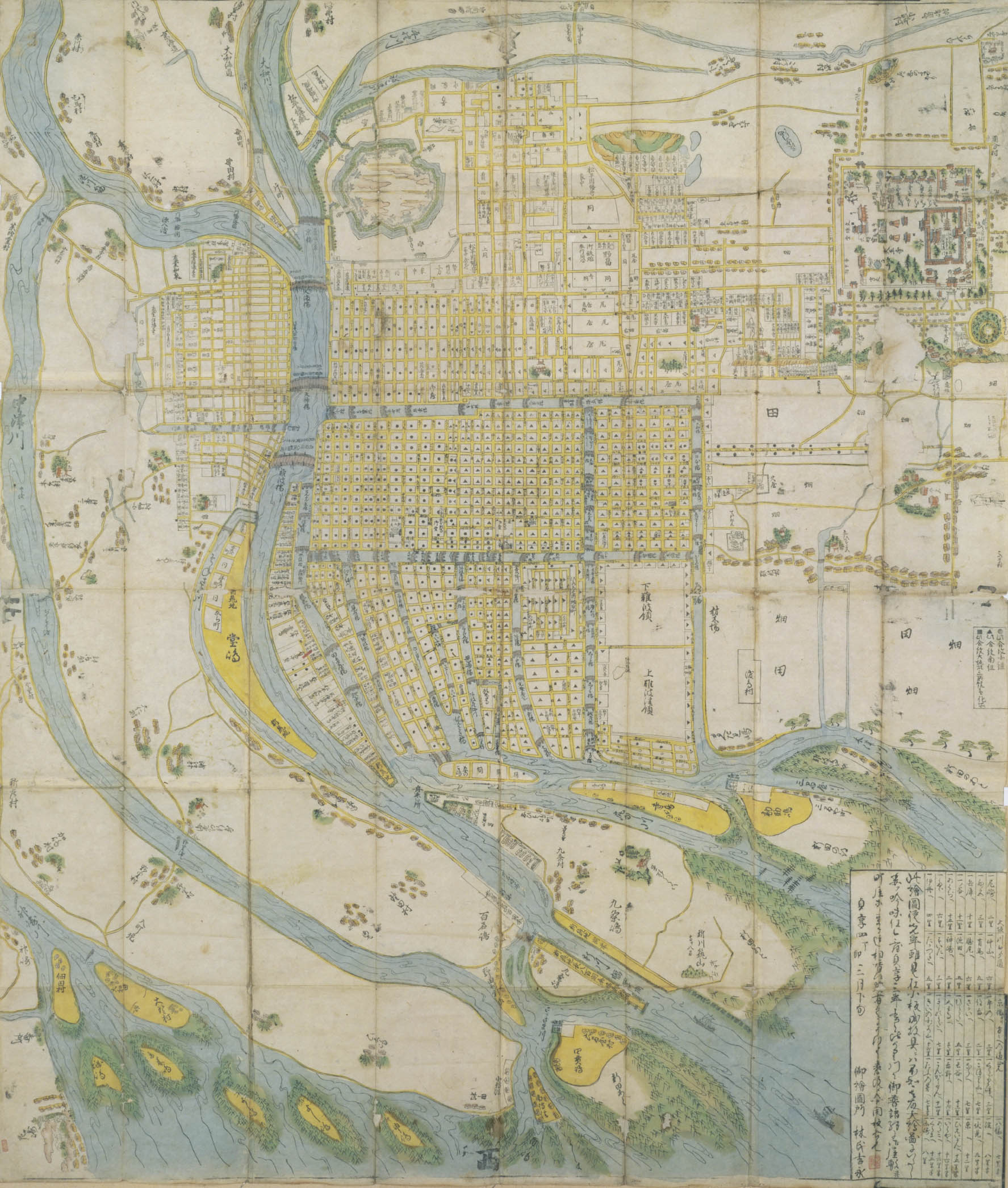

*North is to the left side of the map.

The Spatial Structure of Late Seventeenth-Century Osaka

In 1687, cartographer Hayashi Yoshinaga composed the above map of early modern Osaka. Using it, let us explore city’s spatial structure.

The map includes areas as far north as the Nakatsu River, as far east as the Hirano River, and as far west as Osaka Bay. Therefore, it includes not only the Osaka city area, but also the rural village communities that surrounded the city. Many other early modern maps of Osaka cover the same territorial scope.

The inner structure of Osaka Castle is not depicted in detail. The areas surrounding the Castle that are not marked with the symbols ● and ▲ were the site of warrior estates. Such areas can be found immediately to the west and south of the Castle. They include the Osaka Castellan’s estate, residences of members of the castle guard, and the residential compounds of various warrior officials, including the Shogunal Storehouse Steward, Treasury Steward, Rifle Steward, Archery Steward, Armor Steward, and Lumber Steward.

The area directly to the south of the warrior estates includes agricultural fields and lands that were under the control of a commoner named Terashima Tōemon. A tile producer by trade, Terashima was one of early modern Osaka’s so-called “three great commoners” (sandai chōnin) . Together with Yamamura Yosuke and Amagasaki Mataemon, Terashima was contracted by the Tokugawa House to perform a range of official functions. In exchange, he was granted a range of special privileges, including the right to possess a sword and surname and conduct business with Osaka Castle. The Karahori, or Waterless Canal, was located at the southern edge Terashima’s territory. It comprised the southern part of the external barrier constructed around Osaka Castle by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. In addition, the Ō River comprised the northern portion of that barrier, while the Higashiyoko Canal the Nekoma River respectively comprised its western and eastern portions. Collectively, these four waterways formed Osaka Castle’s outermost line of defense. A long roadway stretched south from the Karahori towards Shitennō Temple. The map shows that it was lined on both sides by buildings. This area was known as Hiranomachi. Once a populous residential community, it is believed that the residents of Hiranochō left the area after being invited to live inside the city proper. After the area’s former residents moved to Osaka, various types of Buddhist temples, excluding those affiliated with the True Pure Land sect, gathered in Hiranochō, transforming the area into a “temple district” (teramachi). That transformation began during the 1580s and continued into the early 1600s. Excluding a portion of the territory controlled by Terashima Fujiemon, all of the areas mentioned above overlap geographically with the castle and castle town that existed during the Toyotomi era (1583-1598). They represent the portion of the city area that Toyotomi planned to construct along the Uemachi Plateau. Although Toyotomi’s plan was never fully realized, it called for the establishment of an urban settlement extending from Osaka Castle to Shitennō Temple and then onward to Sakai.

As noted above, shortly before his death in 1598, Hideyoshi ordered the construction of a third keep around Osaka Castle to protect his young heir. At the same time, he initiated efforts to develop tracts of low-lying swampland located to the west of Higashiyoko Canal (the Senba area) in order to provide commoners displaced as a result of the construction project with an alternative place to live. As a result of his efforts, the direction of urban development in Osaka shifted from a north-south axis to an east-west axis. By the early seventeenth century, the city area extended to the western edge of the Senba area. During that period, the city authorities continued efforts initiated in the 1590s to construct a network of canals to the west of the Uemachi Plateau. In addition, they continued to encourage the development of the tracts of land lining the canals. After the Battle of Osaka, a series of canals were constructed in the Nishi Senba and Shimanouchi areas. In those areas as well, residential tracts were erected alongside the newly-constructed canals. While urban settlements in the Senba area was laid out in a square pattern, those in neighboring Nishi Senba were laid out in a rectangular pattern. Internally, the streets in Nishi Senba curved in accordance with the shape of the canals that traversed the neighborhood. The differing layouts of the Senba and Nishi Senba areas reflect the different stages in Osaka’s incremental urban development.

The development of northern Osaka’s Tenma district began in 1585 with the construction of Tenma Hongan Temple and formation of a surrounding urban settlement. Ultimately, the Tenma area was integrated into early modern Osaka as one of the city’s three commoner districts (sangō). However, the fact that Tenma continued, during the seventeenth century, to be referred to in official documents as “Osaka’s Tenma Town” indicates that the area developed independently of the urban settlements to the south and west of the Osaka Castle. A number of prominent temples and shrines, including Tenmangu and Kōshoji, were located in the center of Tenma district. On the district’s north end, there was a heavy concentration of Buddhist temples, which spread out from east to west. In addition, the residences of lower-ranking officials from the Osaka City Governor’s Office were located on Tenma’s northern edge and along the banks of the Ō River in Yorikimachi and Dōshinmachi.

In the Nakanoshima area, which was located immediately to the south of Tenma, large domainal storehouses known as kurayashiki lined the banks of the Ō River. They were called storehouses because they were originally established as a place to store the annual rice tribute and domainal commodities sent to and sold in Osaka. More than storage facilities, these storehouses also performed an important political function. Namely, they served as a vital link between the Bakufu government, which was based in Edo, and the various domains in Western Japan. Importantly, most storehouses were not located on the grounds of warrior estates. Rather, they were constructed on land officially designated for commoners. On the above map, the tracts of land occupied by these storehouses bear the name of the lord of the domain with which they were affiliated, such as Matsudaira Aki-no-kami and Arima nakatsukasa.

In Nishi Senba, which was located further south, there is an area known as Shinmachi that is completely encircled by narrow canals. During the early modern period, Shinmachi was the site of Osaka’s only officially sanctioned pleasure quarter. In addition, even further south, there was a long narrow district known as Nagamachi, which jutted out from the city’s edge. Located at the northern terminus of the Kishū Highway, it was the site of a large number of inns and flophouses.

At the time that Hayashi’s 1687 map was composed, the Horie and Dōjima neighborhoods had yet to be constructed Dōjima was constructed shortly after the map’s publication, while Horie’s development began in 1698 with the construction of the Horie Canal.

From the late-seventeenth century to the early-eighteenth century, the Bakufu carried out a series of flood prevention construction projects on the Yodo and Yamato River systems. In Osaka, the riparian and river construction projects directed by an individual named Kawamura Zuiken were of particular signifiance. In addition to dredging river bottoms and widening riverways in order to improve water flow, Zuiken constructed the Aji River. A linear waterway, the Aji River was positioned near the mouth of other more serpentine waterways. The above map was composed shortly after the completion of the Aji River. At that point, it had yet to be officially named the Aji River and is simply referred to as the “new river” (shinkawa). As a result of these projects, new tracts of land, including the Horie and Dōjima districts, were opened on the city’s western periphery and a port was constructed at the mouth of the Aji River. In addition, after Zuiken’s death, the course of the Yamato River was redirected in an effort to further limit flooding.

Entering the eighteenth century, efforts to reclaim and develop new tracts of land on the city’s outer edge continued. However, they were smaller in scale and did not include major land reclamation efforts. In that sense, the development of the early modern Osaka city area was almost entirely complete by the end of the seventeenth century.

Early Modern Osaka’s Administrative Structure

As described above, the reconstruction of Osaka Castle and surrounding city area after the Battle of Osaka was almost entirely complete by 1630. At the same time, by the early 1630s, its administrative structure was almost entirely in place. In this section, let us examine that structure.

The Bakufu’s chief representative in Osaka was the Osaka Castellan (Osaka jōdai). Influential hereditary vassals of the Tokugawa clan, who had already filled other important administrative positions, including that of chief Bakufu representative in Kyoto, were generally appointed as Osaka Castellan. The position of Castellan marked an important step on the path of advancement to the position of Bakufu Elder (rōjū). In addition, there were the various captains who supervised the guard units charged with protecting Osaka Castle. Also, there were various lower-ranking official posts, such as Storehouse Steward, Treasury Steward, Rifle Steward, Archery Steward, Armor Steward, and Lumber Steward.

The Osaka City Governor (Osaka machi bugyō) supervised the city’s civil administration. Throughout the Tokugawa period, there were two governors, the Eastern City Governor and the Western City Governor. Below the governors in the chain of command were large groups of warrior officials known as yoriki and dōshin, who filled positions in the city government. There were two governor’s offices, the Eastern City Governor’s Office and the Western City Governor’s Office. The two offices were referred to as such because of their relative geographic locations within the city. It was not the case that one governed the eastern part of the city while the other governed the western part. Both offices shared responsibility for all commoner areas of the city. The governors supervised all areas of civil administration, including policing and civil and criminal courts. In addition, they enacted laws and ordinances, which were generally issued in the form of official proclamations, or fure. Accordingly, Osaka’s City Governors had a major impact on urban society in early modern Osaka. The samurai officials under their authority executed specific official duties. Some were charged with policing duties, while others handled land administration and investigated civil complaints.

Osaka’s commoner districts (chōninchi) were divided into three districts: Kita District, Minami District, and Tenma District. Collectively, the three districts were known as the Osaka sangō. While the districts were geographic agglomerations, new chō subsequently added on the city as a result of land reclamation projects were not necessarily integrated into the district to which they were closest. Accordingly, some areas of the city existed as detached territories located far from the districts with which they were affiliated. On the above map, areas marked with a ● symbol were part of Kita District, while areas marked with a ▲ symbol were part of Minami District. In addition, all of the commoner areas without a marking were part of Tenma District.

An administrative office (sōkaisho) was established in each district and several district chiefs (sōdoshiyori) were appointed to administer district affairs. In addition to the chiefs, various functionaries, including general representatives (sōdai), secretaries (monokaki), office guards (kaishomori), and scribes (hikkō), worked at each district office.

Each of Osaka’s three districts was comprised of hundreds of individual chō, or block associations. The chart below lists the number of chō and number of land parcels in each district during the second half of the eighteenth century. It also includes the location of each district office.

|

|

Chō |

Land Parcels |

District Office Location |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Osaka’s Three Districts |

620 |

18,944 |

|

|

Kita District |

250 |

7,272 |

Hiranomachi 3-chōme |

|

Minami District |

261 |

8,181 |

Minami nōninmachi 1-chōme |

|

Tenma District |

109 |

3,451 |

Tenma 7- chōme |

Early modern Osaka’s commoner population was between 350,000 and 400,000. In contrast, it is likely that the city’s total population included only about 10,000 members of the warrior status groups. Even if you factor in monks and religious practitioners, who were not included in commoner population registers, it is clear that Osaka’s population was characterized by an extremely high ratio of commoners. In other words, persons of commoner status comprised the overwhelming majority of the city’s population.

Together with Kyoto and Edo, Osaka was widely considered one of early modern Japan’s “three great cities” (santo). However, an examination of the demographic composition of the three cities reveals that each had distinct characteristics. Edo, the largest of Japan’s early modern cities, had 500,000 warriors and 500,000 commoners. Although Kyoto was similar to Osaka in that there were a relatively small number of warriors and a vast number of commoners, its population also included a unique preponderance of nobles, Shinto priests, and Buddhist monks. In addition, there were differences in spatial structure and administrative organization. While each city was governed by a City Governor and partitioned into hundreds of chō, Osaka’s three districts and the mode of existence of the city’s landholders served to distinguish it from Kyoto and Edo.