【Translation】

The foregoing register was composed in such a way that its content is the same as that contained in land registers submitted in previous years. We have entered the names of the current landowners into this register and submit it to you now. The number of households and total tax burden for the chō are different than indicated in previous registers. This is because landowners with large residential lots have partitioned or sold off a portion of their lots, and the children of those landholders who received partitioned lots have come to be counted among the total number of households. As a result of this process, the total residential tax burden has increased. At the same time, when a number of small lots have been purchased and combined into a single large lot, the number of households has decreased. However, even when a number of small lots have been combined into a large lot, we will ensure that the combined tax burden of the formerly separate lots is not at all reduced. Because forty years have elapsed since the previous land register was composed, the owners of some of the lots have changed several times. Yet, if we compare this land register with the last one, the frontage and depth of each of the plots in the chō is perfectly accurate. Therefore, all local landholders have affixed their seals and we now submit this newly composed land register. For future reference, the facts are as indicated above.

|

The Twenty-Eighth Day of the Fifth Month of Meireki 1 |

Minami kobikimachi kitanochō Headman Kyuya. Monthly Representative Tōbē |

(*The document contains a series of notations indicating that it was amended and re-submitted to the Land Administration Department at the City Governor’s Office in the tenth month of Genroku 7 (1694), the fourth month of Kyōhō 11 (1726), the tenth month of Hōreki 3 (1753), the twelfth month of An’ei 7 (1778), the fifth month of Kansei 10 (1798), the fifth month of Bunka 12 (1815), the eleventh month of Bunsei 8 (1825).

The foregoing cadastral register was last amended in the Bunsei period (1818-1830) and many years have passed since then. Since the register was last amended, residential lots have been partitioned and many landowners have moved in and out of the chō. As a result, it became increasingly difficult to distinguish previous landowners from current landowners. We recently received an official inquiry regarding the frontage (omoteguchi) and depth (okuyuki) of the lots in our chō. Because the frontage and depth of each of the lots in the chō has not changed since it was previously checked, the current landowners have signed and sealed this document and submit it to you now. Also, the sealed statement that we submitted with previous versions of this letter is included above. For future reference, the facts are as indicated above.

| The Fifth Month of Ansei 3 (1856) Asaoka Sukenojō-dono Hagino Shichizaemon-dono Isoya Tanomo-dono Niwa Kinjirō-dono Uchiyama Hikojirō-dono Naruse Kurōzaeomon-dono Katsube Yoichirō-dono Yamamoto Zennosuke-dono |

Kobikimachi kitanochō Headman Daimonjiya Mokuemon (㊞) Monthly Representative Daimonjiya Sadahachi (㊞) |

【Key Terms and Phrases】

Omote (面)….In this case, the character 面is read omote. It refers here to the text or content of the document. / Iekazu (家数)….The number of residential plots within the chō / Yakusū (役数)…The tax burden that was assessed on each residential plot / Mizuchō (水帳)…Land registers that were composed for each chō / Ienushi (家主)…The owner of a residential plot; also known as an iemochi (iemochi) / Maguchi(間口)….The frontage of a residential plot / Yonjūnen ni oyobi sōrō yue (四拾年ニ及候故)….A phrase meaning “because 40 years have elapsed”;From this phrase, it is possible to determine that the previous land register was produced in 1616. It is also important to note that the early modern method of counting years is different than the current method. Namely, individuals were listed as one year old during their year of birth and another year was added to their age on the first day of the new year. / Urayuki (裏行)….The depth of a residential plot / Minami kobikimachi kitanochō (南木挽町北之丁)….During the period in question, Kobikimachi kitanochō was referred to as Minami kobikimachi kitanochō. / Toshiyori (年寄)….The toshiyori, or chō headman, served as the chief representative of local landowners and played a central role in the chō’s daily administration. / Gatsugyōji or Gachigyōji (月行司)….The gatsugyōji assisted the toshiyori in administering the affairs of the chō. It was an alternating monthly position. In many chō, it was normal to have two gatsugyōji on duty each month. However, in smaller chō, such as Kobikimachi kitanochō, there was only one gatsugyōji. / Okugaki (奥書)….A sealed statement at the end of a document, which serves to guarantee its content / Kobikimachi kitanochō (木挽町北之丁)….In some cases, the character 南 was dropped and the chō in question was referred to simply as Kobikimachi kitanochō. / Daimonjiya Mokuemon (大文字屋杢右衛門)….During the Meireki period (1655-1658), the Daimonjiya family did not have a separate firm or shop name (yagō). However, during the period in which this land register was composed, the entire Daimonjiya family, including all of their rental dwellings, had come to possess a firm name. It should also be noted that a seal has been affixed to the firm’s name. / Asaoka Sukenojō (朝岡助之丞)….During the period in question, Asaoka Sukenojō and the seven other individuals listed after him were officials in the Land Administration Department (jikata yakusho) at the City Governor’s Office. The Land Administration Department handled all affairs related to land management in Osaka.

owned by Osaka City University

【Explanation】

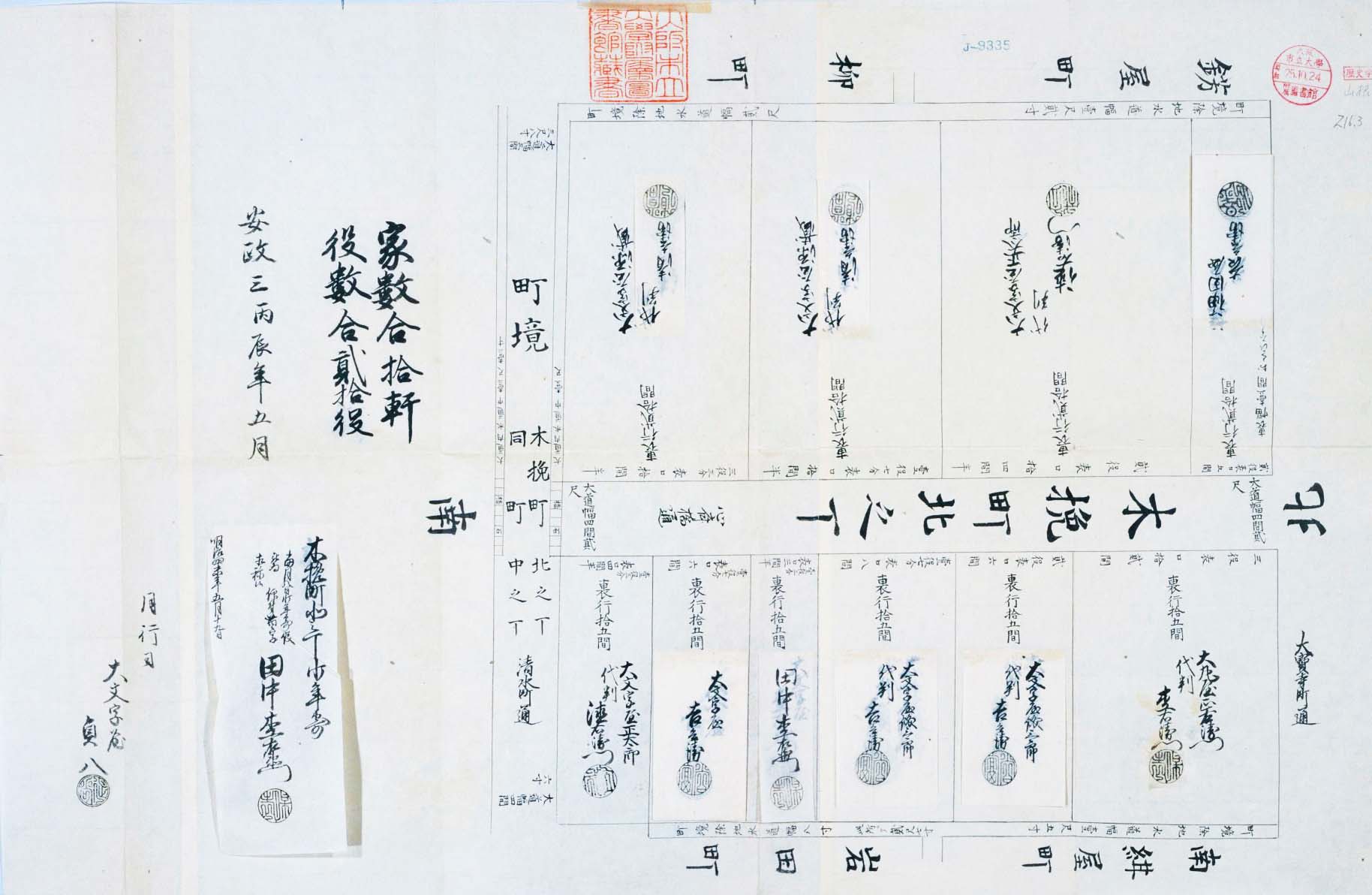

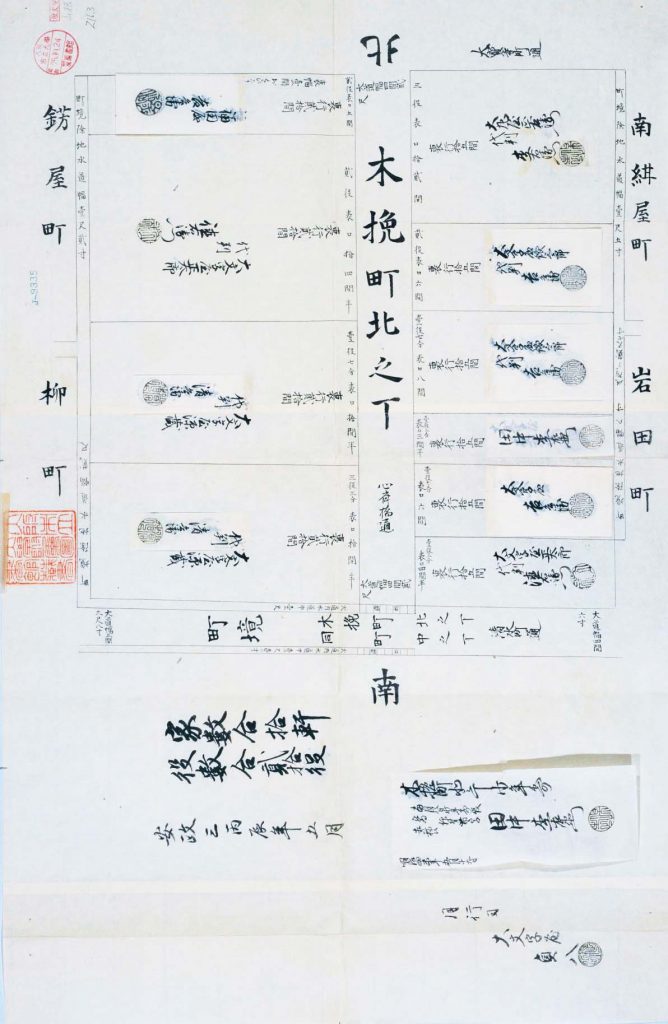

The above document is a mizuchō ezu, or cadastral map. Cadastral maps were prepared in each chō together with land registers known as mizuchō. Land registers list the width and depth of each land parcel, the associated tax burden (yakusū), and the owner’s name. The yakusū served as the standard by which Bakufu-issued taxes and payments to the chō were assessed. Initially, each land parcel had a uniform taxation standard of one yaku. However, as individual parcels were merged and partitioned, taxation standards became increasingly heterogeneous. As a result, the taxation standard for individual land parcels came to be specified in the land register for each chō.

Land registers and cadastral maps were stored in three places: the chō, the district office of the district of which the chō was part, and the City Governor’s Office. When the owner of a specific land parcel changed as a result of an inheritance or sale, it was reported to the chō. Once it had been reported to the chō, subsequent reports were made to the district office and the City Governor’s Office. The specific details of the change were written on a small piece of paper, which was then pasted on to the section of the land register in which the parcel was listed. Over time, the number of such papers increased and registers became difficult to maintain. As a result, every twenty or thirty years, the City Governor’s Office ordered each chō to prepare new registers.

The headmen and monthly representatives of each chō sealed both the land register and cadastral map for their chō. Both documents were then submitted to officials in the Land Administration Department at the City Governor’s Office. However, most of the early modern land registers and cadastral maps that have been preserved were not stored in the City Governor’s Office. In fact, most come from one of the city’s three district offices or a specific chō.

Let us now examine the details of the above cadastral map. The map is from Kobikimachi-kitanochō, a chō in Osaka’s Minami District. It was composed in the fifth month of Ansei 3 (1856). As the map indicates, Kobikimachi-kitanochō was partitioned into 10 residential lots and had a combined tax burden (yakusū) of 20 yaku. Headman Daimonjiya Naoemon and monthly representative Daimonjiya Sadahachi have both sealed the map. The document also contains markers indicating the four directions of north, south, east, and west. As the map shows, the chō in question straddled Shinsaibashi Boulevard, a north-to-south-running thoroughfare. 8.5 meters in width, the thoroughfare was known as Shinsaibashi Boulevard because it extended south from Shinsaibashi Bridge. All of the residential lots in Kobikimachi-kitanochō were located along Shinsaibashi Boulevard. Today, the street is the site of one of Osaka’s most popular shopping arcades.

Although most of the chō in early modern Osaka extended east-to-west, Kobikimachi-kitanochō spread north-to-south. An east-to-west-running thoroughfare known as Daihōji Street was located on the chō’s northern edge. A chō called Kazariyachō was located on the northern side of Daihōji Street. In addition, a second east-to-west-running thoroughfare called Shimizuchō Street was located on Kobikimachi-kitanochō’s southern border. A chō by the name of Kobikimachi-nakanochō was located just south of Shimizuchō Street. The western half of Shimizuchō Street was approximately 7.1 meters wide, while the eastern half was approximately 8.1 meters wide. As the map indicates, a shallow drainage ditch lined both sides of the western half of Shimizuchō Street. The ditch on the northern side of the street was 30 centimeters wide, while the ditch on the southern side was 33 centimeters wide. Stone bridges were constructed at the points that Shinsaibashi Boulevard intersected with the northern and southern ditches.

The western block of Kobikimachi-kitanochō was divided into four residential lots. Each lot had a depth of approximately 39.4 meters. Behind the four western lots, there was a shallow drainage ditch, which also marked the boundary between Kobikimachi-kitanochō, on the one hand, and Kazariyachō and Yanagichō, on the other. On the Kazariyachō side, the ditch was 36 centimeters wide. On the Yanagichō side, it was 60 centimeters wide.

In contrast, the eastern block of Kobikimachi-kitanochō was partitioned into six residential lots. The depth of each lot was approximately 29.5 meters. Therefore, the depth of the residential lots on the eastern and western sides of Kobikimachi-kitanochō was different. Behind the plots on the eastern side, there was also a drainage ditch, which marked the boundary between Kobikimachi-kitanochō, on the one hand, and Minami-konyachō and Iwadachō, on the other. On the Minami-konyachō side, the ditch was 45 centimeters wide and on the Iwadachō side, it was 81 centimeters wide.

The boundaries of the various chō in the vicinity of Kobikimachi-kitanochō intermingled in an extremely complex manner. Even within the same residential lot, lot depth was not necessarily uniform.

Let us examine the structure of Kobikimachi-kitanochō’s western block more closely. The two residential lots on the southern side of the western block both had a frontage of 20.7 meters (10.5 ken) and a depth of 39.4 meters (20 ken). The owner of both lots is listed as Daimonjiya Genzō’s proxy Seibē. However, the tax burden for the northern plot is listed as 1.7 yaku, while the burden for the southern plot is listed as 3.3 yaku. From this example, we can see that tax burdens were not assessed simply based on a residential lot’s size. Rather, they were determined through the merging and partitioning of lots.

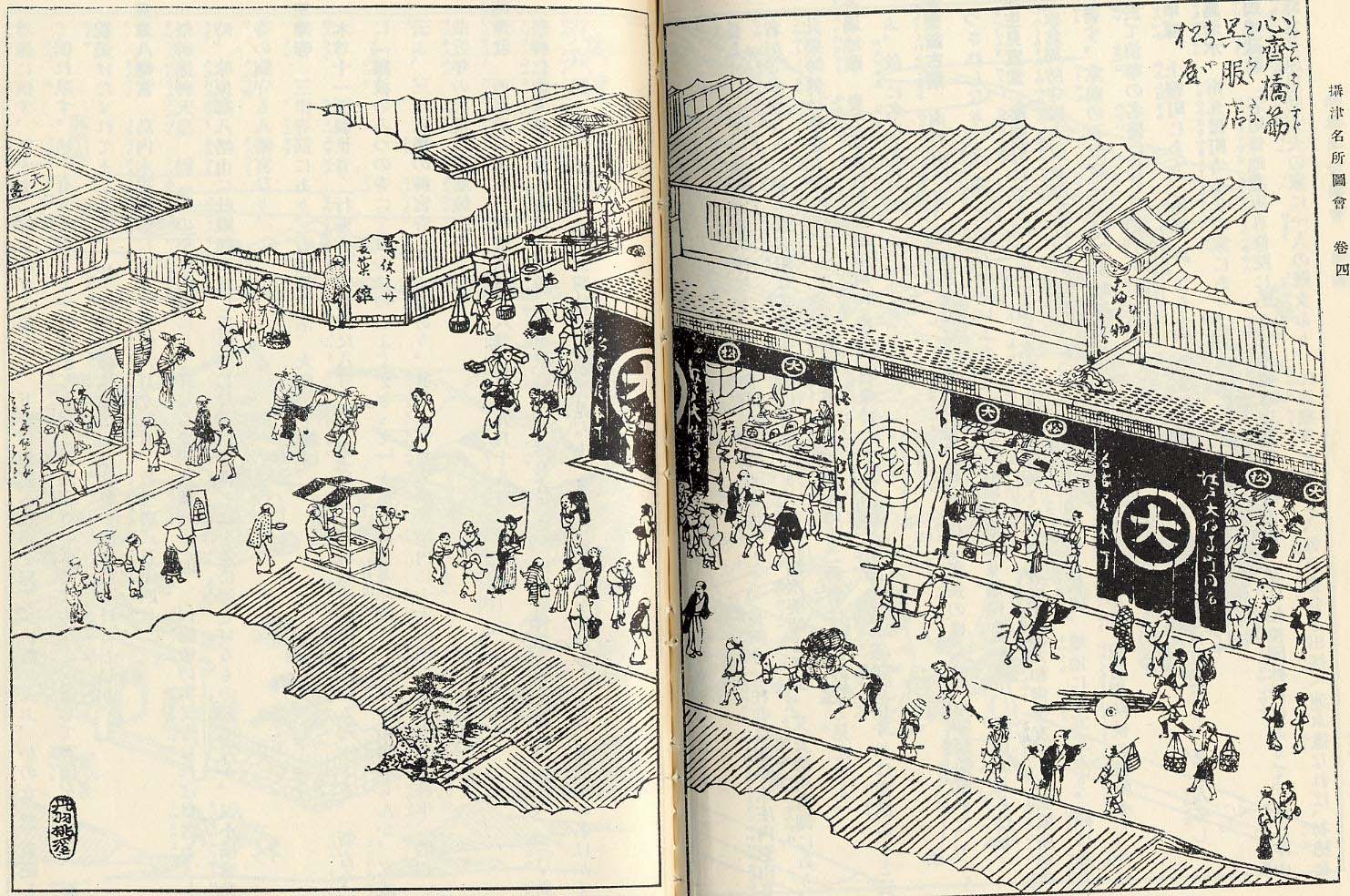

Together, these two lots served as the site of the Matsuya Clothing Shop. The Matsuya Clothing Shop, which was also known by the shop name “Daimaru,” was one of early modern Osaka’s leading clothiers. It was the predecessor of today’s Daimaru Department Store. The Daimonjiya family was originally from Kyoto. In 1726, an associate of the family named Hachimonjiya Jinemon rented a dwelling in Kobikimachi-kitanochō and established the Matsuya Clothing Shop. In the first month of 1728, Hachimonjiya purchased a residential lot in the chō. However, shortly thereafter, Hachimonya ceased his involvement in the management of the Matsuya Clothing Shop. At that point, Hachimonya’s partner, the Daimonjiya family, assumed sole ownership of the shop. From that point onward, the Matsuya Clothing Shop continued to grow and accumulate more land within the chō. Presently, the Daimaru Department Store occupies the entire western block of Kobikimachi-kitanochō, as well as a portion of neighboring Kazariyamachi and Yanagimachi.

Together, these two lots served as the site of the Matsuya Clothing Shop. The Matsuya Clothing Shop, which was also known by the shop name “Daimaru,” was one of early modern Osaka’s leading clothiers. It was the predecessor of today’s Daimaru Department Store. The Daimonjiya family was originally from Kyoto. In 1726, an associate of the family named Hachimonjiya Jinemon rented a dwelling in Kobikimachi-kitanochō and established the Matsuya Clothing Shop. In the first month of 1728, Hachimonjiya purchased a residential lot in the chō. However, shortly thereafter, Hachimonya ceased his involvement in the management of the Matsuya Clothing Shop. At that point, Hachimonya’s partner, the Daimonjiya family, assumed sole ownership of the shop. From that point onward, the Matsuya Clothing Shop continued to grow and accumulate more land within the chō. Presently, the Daimaru Department Store occupies the entire western block of Kobikimachi-kitanochō, as well as a portion of neighboring Kazariyamachi and Yanagimachi.

from “A Collection of Pictures Depicting the Sights of Settsu Province” owned by Osaka Museum of History

This illustration depicts the intersection of Shinsaibashi Boulevard and Shimizu Street as seen from the eastern block of Kobikimachi-kitanochō. The Matsuya Clothing Store stands in the foreground of the illustration.

As noted above, land registers in early modern Osaka were amended each time that the headman or an owner of one of the residential lots within the chō changed. When a change occurred, the details of the change were entered onto a small strip of paper, which was then affixed on to the relevant section of the land register. Let us look at one specific example. In this case, the land register was amended because a new individual assumed the position of Kobikimachi-kitanochō administrator (shōdoshiyori). The strip of paper that was added to the local land register at that time reads, “Kobikimachi-kitanochō, On the eighth day of the fifth month, Naoemon was given the surname Tanaka and appointed as administrator. 19/5/Meiji 4 (1871).” In the fifth month of 1871, the official position of chō headman (toshiyori) was abolished. In place of the headman, local administrators known as shōdoshiyori were appointed in each chō. Therefore, the land register was amended in such a way that Daimonjiya is listed not as headman, but as administrator. In addition, the strip of paper that was added to the land register indicates that Naoemon was not only appointed as chō administrator, but also given a new surname. Because the first name and seal of the individual who was appointed administrator is the same as that of former headman Daimonjiya Naoemon, it is likely that Daimonjiya became chō administrator after the position of headman was abolished. Although the urban administrative system was reorganized following the Meiji Restoration, Tokugawa-era-style cadastral maps continued for the time being to serve as the chō’s basic landholding record.