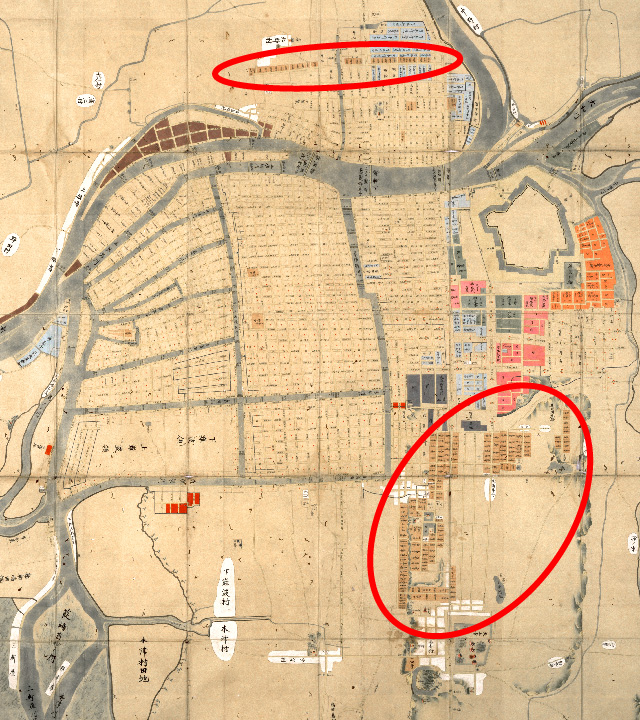

Hero Image: ”The Map of Osaka’s Three District(Jōkyō-era)” owned by Osaka Museum of History

大坂三郷町絵図(貞享) 大阪歴史博物館所蔵

Introduction

During the next four weeks, we will be discussing early modern or Edo-period Osaka. Since the Meiji period, the second character in the place name Osaka has been written using the kozato radical. However, during the Edo period, people used the tsuchi radical instead. Accordingly, when you see the place name written using the tsuchi radical, please know that it refers to Edo-period Osaka. During the four lectures, we will examine the unique features of early modern society through an examination of the various social organizations established by Osaka’s residents, such as the neighborhood association and occupational fraternity. Accordingly, we will only deal in passing with the economic and cultural images commonly associated with Edo-era Osaka, including its role as “the Shogunate’s commercial center” and locus of “Genroku culture.”

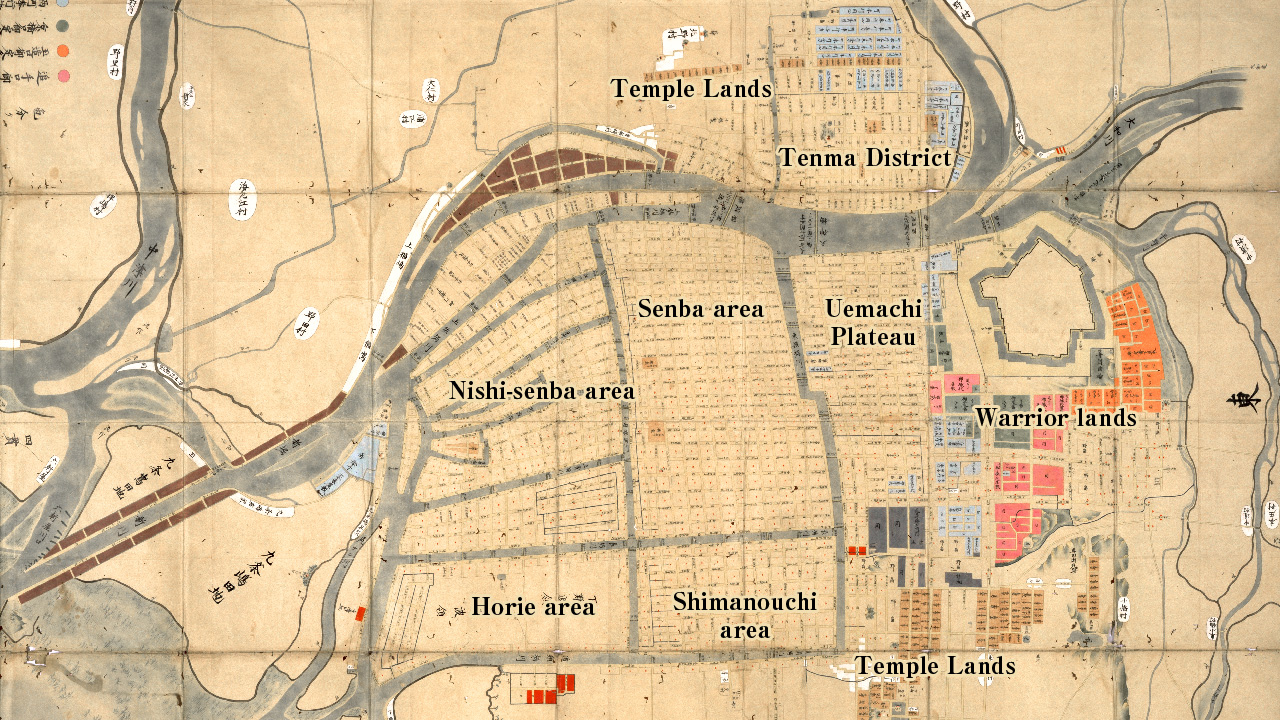

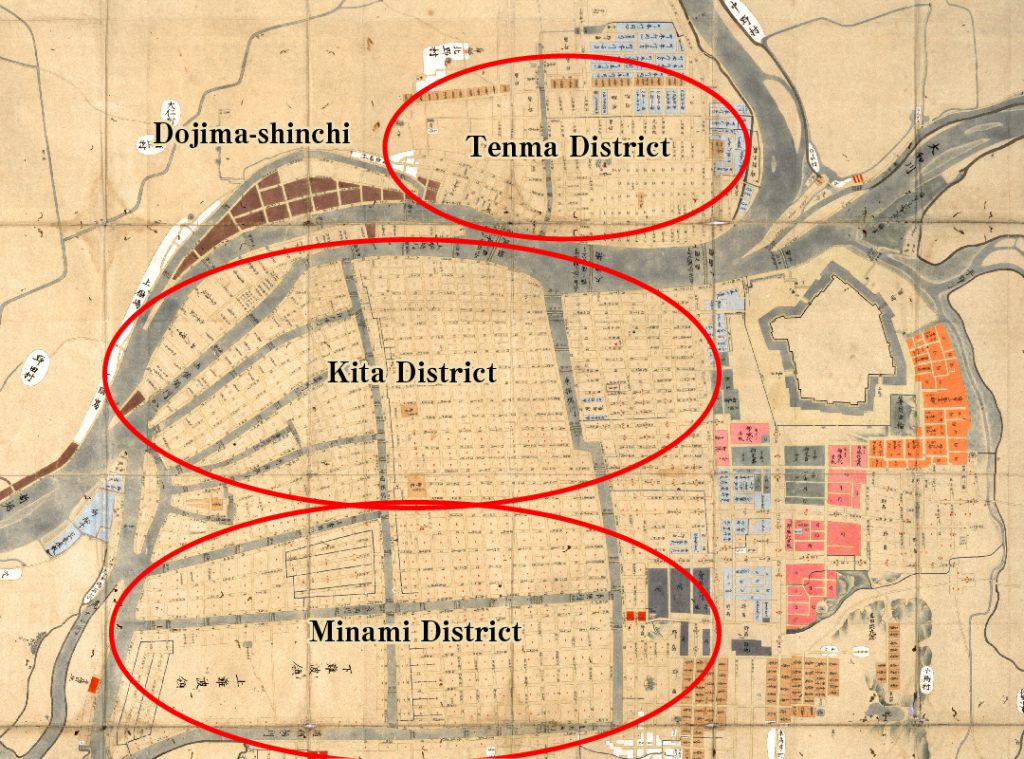

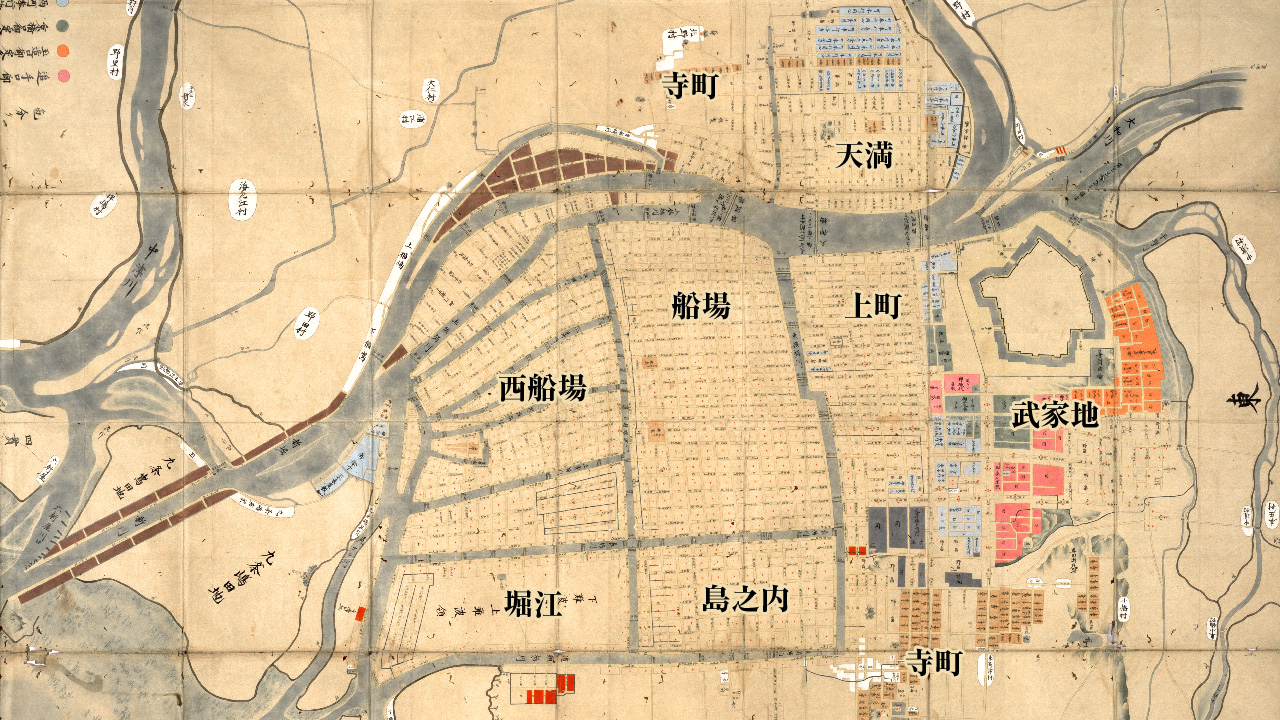

During the first of our four lectures, we will begin by discussing the unique features of urban society and then confirm the geographic extent of the early modern Osaka city area. Edo-era Osaka was partitioned into several distinct spatial segments, including Osaka Castle and the surrounding warrior lands, temple lands on the northern edge of Tenma district and on the southern tip of the Uemachi plateau, and commoner lands, which extended from Uemachi to the Senba, Nishi-senba, Shimanouchi, Horie, and Tenma districts (Use conceptual map).

Using an Edo-era map of Osaka, let us examine the city’s segmental structure. Adding complexity to our discussion is the fact that the official depots established in Osaka by Western Japanese domainal governments were located on commoner lands.

1. The Characteristics of Early Modern Society

From the late-sixteenth to the early-seventeenth centuries, during the era in which Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu were active, a major transformation occurred on the Japanese archipelago (Use an illustration while explaining the following section). In rural Japan, a traditional society based on the household and village formed. That society remained in place for centuries and was only fully dismantled during “the era of high-speed growth” in the 1960s. At the same time, the Edo era was also characterized by dramatic urban development. In addition to the three megacities of Edo, which boasted a population of 1,000,000, and Osaka and Kyoto, which had populations in the hundreds of thousands, it saw the formation of smaller castle towns across the Japanese archipelago. Both megacities and smaller towns were partitioned into units known as chō or neighborhood associations. Neighborhood associations were communal organizations of landholders who owned residential tracts on both sides of a shared street. These associations served as the basic unit of urban life for early modern city residents. Although we will examine the neighborhood association in detail during a later session, I would like to note that it was the urban counterpart of the rural village, serving as one of the two basic units of early modern society.

These villages and neighborhood associations were at once local units of Bakufu and domainal administration, and communal organizations which supported the lives and livelihoods of their constituents. During the early modern period, they were not, however, the only publicly-sanctioned social organizations. Occupational associations founded by merchants and artisans, as well as fraternal organizations established by performers, religious practitioners, and members of the eta and hinin status groups also received official recognition from the authorities and had a distinctly public character. As this suggests, early modern Japanese society was one organized around the principle of status in which a vast array of self-regulating and internally stratified social groups was organized into a composite network. Unlike contemporary society, therefore, it was a one in which there was no clear distinction between “public” and “private.”

Namely, early modern rule was mediated by social organizations, such as the neighborhood association, village, and occupational association. Accordingly, the regulation of the individual was entrusted to the social organization. As a consequence of this arrangement, individual villages and neighborhood associations were called upon to produce and maintain official records. In addition, as both the village and neighborhood were self-regulating associations intimately connected with the lives and livelihoods of their constituents, they had to produce their own by-laws and other internal documents. This dual necessity ultimately compelled the production and preservation of a wide array of local records throughout the early modern period.

Throughout the Edo era, therefore, neighborhoods and villages produced and maintained a massive volume of local records. Even though only a portion of those records survive today, the amount and array is truly astonishing. Considered from a global perspective, the survival of local records produced by ordinary people on a such a vast scale is truly rare and an expression of the unique features of early modern Japanese society. Entering the modern period, however, social organizations were stripped of their official character and, as a result, villages and neighborhoods stopped producing their own internal records. In many rural villages, however, shrine associations, which formed during the early modern period and persisted after Meiji Restoration, continued to produce their own records until “the era of high-speed growth” (Show photograph of the Iamzaike Village Shrine Association Register, which includes successive entries from the Shōtoku period to the Taishō period). As this suggests, when we consider the major political transformations that accompanied the Meiji Restoration, it is also essential to consider the enduring character of traditional society, which persisted in the individual’s sphere of everyday life.

With the foregoing analysis in mind, I would like to discuss the character of the early modern records that have been preserved and the nature of urban social groups. In order to foreground our discussion, I will first consider the geographic extent and segmental structure of early modern Osaka.

2. Urban Osaka’s Segmental Structure

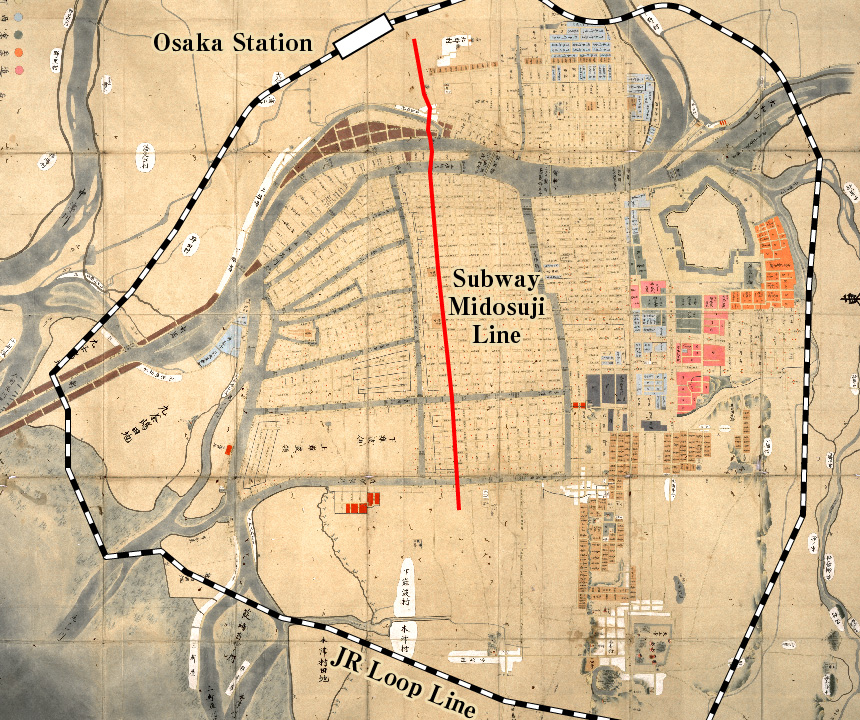

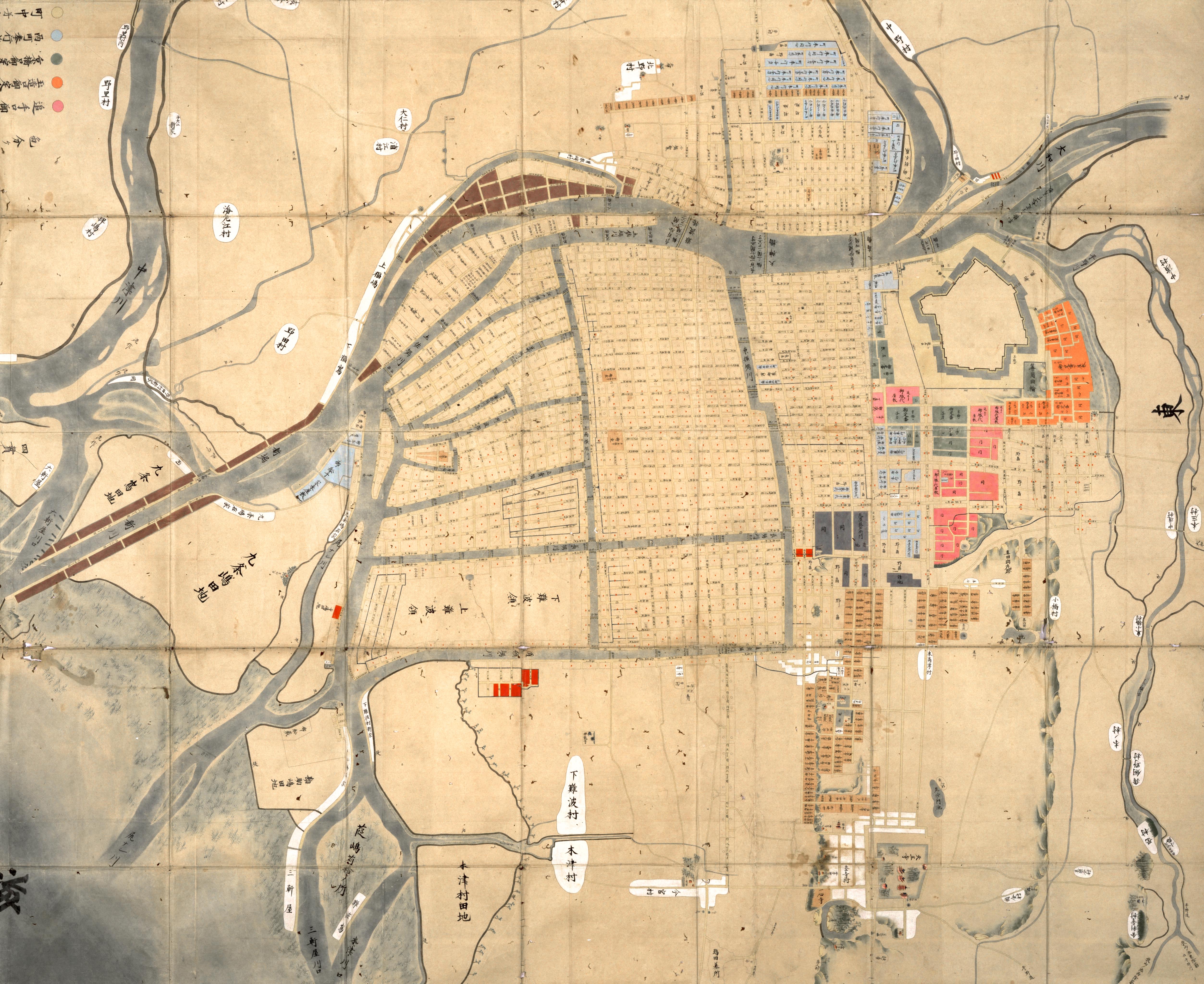

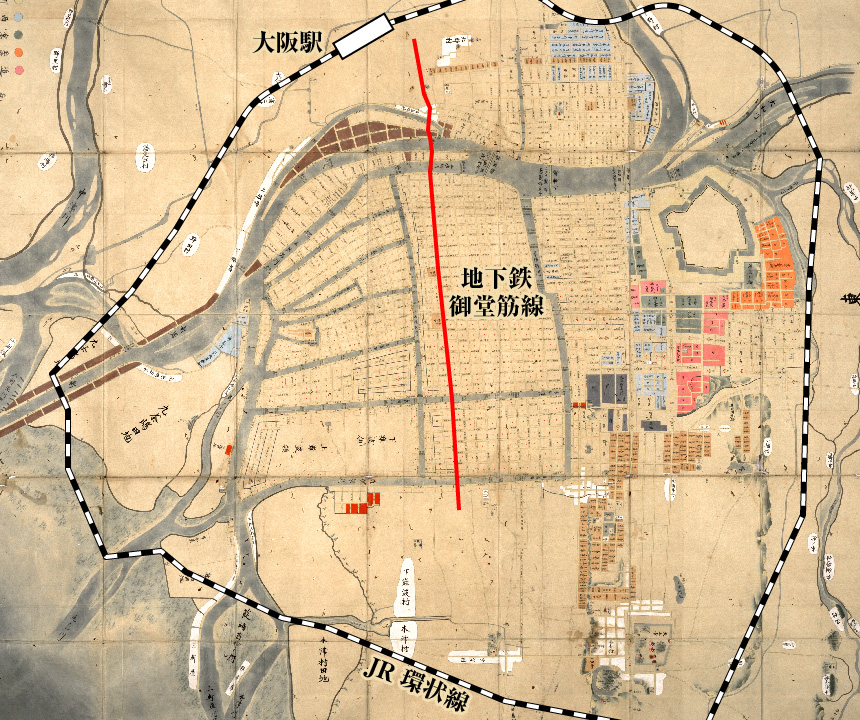

This is a map of Osaka during the 1680s. Although the city area experienced some limited expansion after this period, the area shown in this map depicts the spatial extent of early modern Osaka. A comparison of this map with one depicting present-day Osaka’s boundaries reveals that the early modern city of Osaka overlapped with the area within the boundaries of the northern two-thirds of the JR Osaka Loop Line. The northern portion of Sonezaki-shinchi district is the site of present-day Osaka Station. The Loop Line then winds around the outer edge of Osaka Castle and continues southward along the eastern edge of the Uemachi Plateau to the Tamatsukuri area. It then continues as far south as the Dōtonbori area, ultimately traveling as far west as the Kizu River.

This is a map of Osaka during the 1680s. Although the city area experienced some limited expansion after this period, the area shown in this map depicts the spatial extent of early modern Osaka. A comparison of this map with one depicting present-day Osaka’s boundaries reveals that the early modern city of Osaka overlapped with the area within the boundaries of the northern two-thirds of the JR Osaka Loop Line. The northern portion of Sonezaki-shinchi district is the site of present-day Osaka Station. The Loop Line then winds around the outer edge of Osaka Castle and continues southward along the eastern edge of the Uemachi Plateau to the Tamatsukuri area. It then continues as far south as the Dōtonbori area, ultimately traveling as far west as the Kizu River.

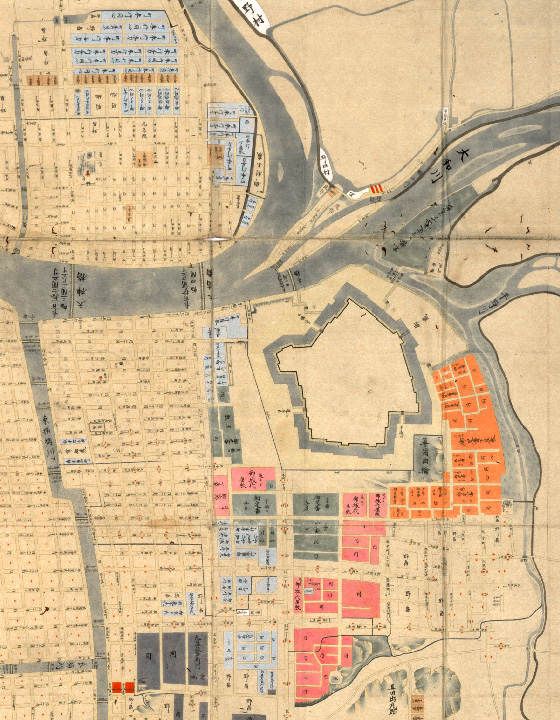

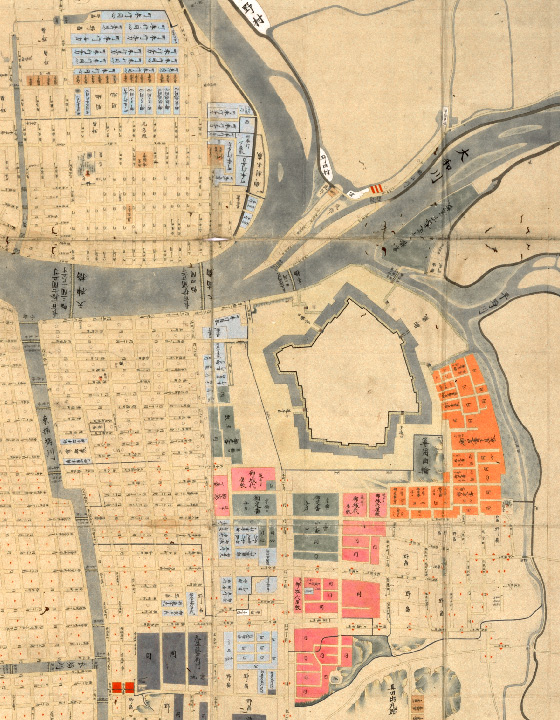

Warrior Lands

In Bakufu-administered early modern Osaka, the Osaka Castellan, captains of the Castle Guard, and other lower ranking officials were appointed to handle all military- and security-related affairs. At the same time, the Osaka City Governor executed urban governmental and judicial affairs. The areas marked in pink, orange, and green in the vicinity of Osaka Castle indicate the location of the estates occupied by the Osaka Castellan and the captains of the Tamatsukuri-guchi and Kyōbashi-guchi Castle Guards. As the Osaka Castellan also commanded Western domainal lords, the Bakufu commonly appointed a hereditary vassal controlling a domain comprised of tens of thousands of koku to serve as Castellan. At the same time, domainal lords possessing holdings of between ten- and twenty-thousand koku were appointed to serve as captains of the castle guard. In addition, there were two guard units which rotated annually and four deputies who administered security affairs. However, because all of these individuals resided within Osaka Castle, their place of residence is not depicted on the map.

In Bakufu-administered early modern Osaka, the Osaka Castellan, captains of the Castle Guard, and other lower ranking officials were appointed to handle all military- and security-related affairs. At the same time, the Osaka City Governor executed urban governmental and judicial affairs. The areas marked in pink, orange, and green in the vicinity of Osaka Castle indicate the location of the estates occupied by the Osaka Castellan and the captains of the Tamatsukuri-guchi and Kyōbashi-guchi Castle Guards. As the Osaka Castellan also commanded Western domainal lords, the Bakufu commonly appointed a hereditary vassal controlling a domain comprised of tens of thousands of koku to serve as Castellan. At the same time, domainal lords possessing holdings of between ten- and twenty-thousand koku were appointed to serve as captains of the castle guard. In addition, there were two guard units which rotated annually and four deputies who administered security affairs. However, because all of these individuals resided within Osaka Castle, their place of residence is not depicted on the map.

The area in light blue marks the residences of the Osaka City Governor, the mid- and low-ranking officials under his authority, and a group of six officials known as the rokuyaku. There were two city governors and they maintained separate administrative offices northwest of Osaka Castle. The site located to the east was referred as the Eastern City Governor’s Office, while the site located to the west was referred to as the Western City Governor’s Office. Although the two city governors were referred to as the Eastern and Western City Governor, they did not divide the city into eastern and western jurisdictions. Rather, the terms “east” and “west” referred to their relative locations within the city. In actuality, Osaka’s two governor’s offices administered municipal affairs on a rotating basis, alternating from month to month. Also, it should be noted that the Western City Governor’s Office later relocated to a site along the Higashi-yokobori River. The yoriki and dōshin (mid- and low-level warrior officials) who worked at both City Governor’s Offices maintained estates a short distance away in northern Osaka’s Tenma district.

In Edo and other castle towns, it was commonly the case that the castle and surrounding warrior estates where the lord’s retainers lived occupied a majority of the city area. However, in the case of Bakufu-controlled Osaka, which had both a Castellan and City Governor, the area occupied by the castle and warrior estates was extremely limited. At the same time, however, there were more than 150 depots inside the city, which were maintained by domainal governments from across Western Japan. If you look closely at the map, you will notice the names of various Western domainal lords in the Nakanoshima area and along the southern bank of the Tosabori River. The names indicate the sites of the domainal depots inside Osaka. Unlike Edo, however, where domainal lords were granted parcels of land, in Osaka, domainal governments had to purchase tracts of land in the city’s commoner districts. In addition, when purchasing land, they had to appoint a commoner to serve as the official titleholder. Accordingly, when considering the history of warrior status in Osaka, it is important to keep in mind that the warrior administrators who managed these domainal depots lived in small numbers in Osaka’s commoner neighborhoods.

In Edo and other castle towns, it was commonly the case that the castle and surrounding warrior estates where the lord’s retainers lived occupied a majority of the city area. However, in the case of Bakufu-controlled Osaka, which had both a Castellan and City Governor, the area occupied by the castle and warrior estates was extremely limited. At the same time, however, there were more than 150 depots inside the city, which were maintained by domainal governments from across Western Japan. If you look closely at the map, you will notice the names of various Western domainal lords in the Nakanoshima area and along the southern bank of the Tosabori River. The names indicate the sites of the domainal depots inside Osaka. Unlike Edo, however, where domainal lords were granted parcels of land, in Osaka, domainal governments had to purchase tracts of land in the city’s commoner districts. In addition, when purchasing land, they had to appoint a commoner to serve as the official titleholder. Accordingly, when considering the history of warrior status in Osaka, it is important to keep in mind that the warrior administrators who managed these domainal depots lived in small numbers in Osaka’s commoner neighborhoods.

Shrine and Temple Lands

The light brown areas on the map indicate the location of temple lands. In the case of Osaka, temples were concentrated in two parts of the city. First, there was a row of temples extending east-west in the northern part of Tenma District. The eastern portion is sandwiched between yoriki and dōshin residences, which are shown in light blue. The second grouping of temples extends southward along the Uemachi Plateau to the northern edge of the massive Shitennōji Temple complex. During the Edo period, most of the city’s Buddhist temples were concentrated in these two areas. The only exception was temples affiliated with the sect of Pure Land Buddhism, which were scattered across the city area. If you look at the Senba area of the map, you will notice a square section shaded light brown. This is the site of the Namba Midō and Tsumura Midō, branch temples of the Eastern and Western Honganji Temples. Present-day Osaka’s main thoroughfare, Midō Boulevard, takes its name from these two branch temples and is a widened version of the street that ran in front of the temples during the Edo period. It should be noted that large shrine complexes, such as Tenma Tenjin Shrine, are also depicted on the map. Like temples affiliated with the Pure Land school, shrines were dispersed across the city area.

The light brown areas on the map indicate the location of temple lands. In the case of Osaka, temples were concentrated in two parts of the city. First, there was a row of temples extending east-west in the northern part of Tenma District. The eastern portion is sandwiched between yoriki and dōshin residences, which are shown in light blue. The second grouping of temples extends southward along the Uemachi Plateau to the northern edge of the massive Shitennōji Temple complex. During the Edo period, most of the city’s Buddhist temples were concentrated in these two areas. The only exception was temples affiliated with the sect of Pure Land Buddhism, which were scattered across the city area. If you look at the Senba area of the map, you will notice a square section shaded light brown. This is the site of the Namba Midō and Tsumura Midō, branch temples of the Eastern and Western Honganji Temples. Present-day Osaka’s main thoroughfare, Midō Boulevard, takes its name from these two branch temples and is a widened version of the street that ran in front of the temples during the Edo period. It should be noted that large shrine complexes, such as Tenma Tenjin Shrine, are also depicted on the map. Like temples affiliated with the Pure Land school, shrines were dispersed across the city area.

A wide array of religious practitioners, including ascetic mountain priests (yamabushi), beggar monks (gannin bōzu), Buddhist performers (rokusai nenbutsu), and Shinto practitioners, also lived in the city of Osaka in back-alley tenements. They survived by wandering the city each day and begging for alms while praying, performing purification rituals, and distributing paper charms from temples and shrines.

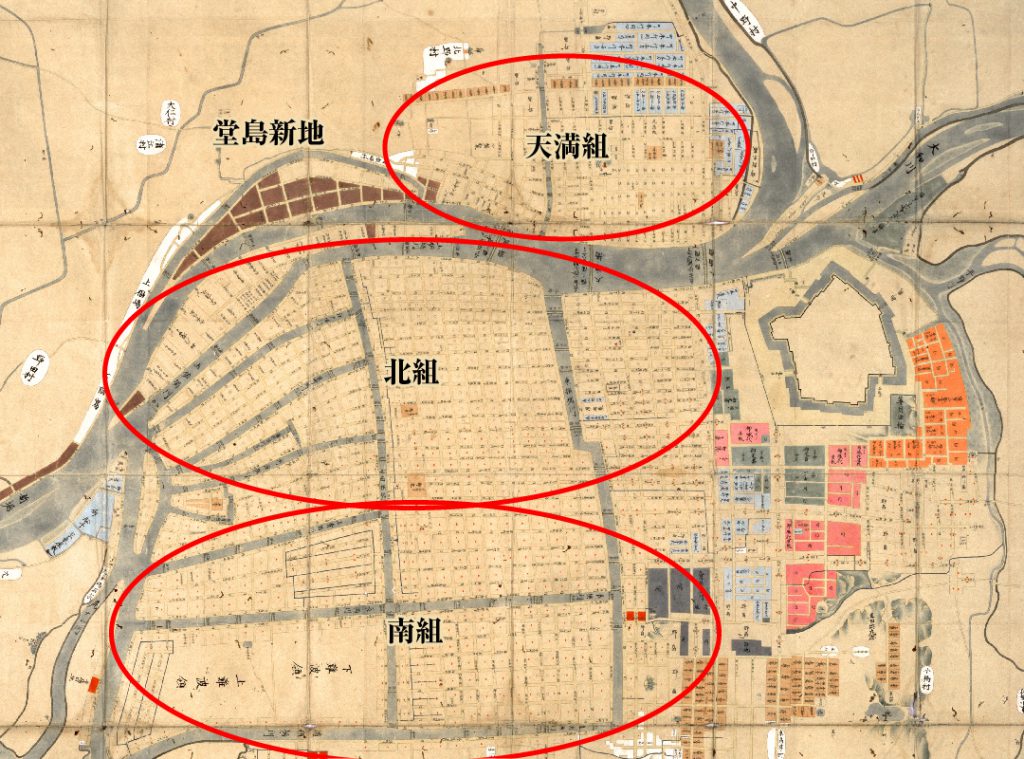

Commoner Lands

The sections of the map arranged in a grid-like pattern indicate the location of Osaka’s commoner lands. Those lands were divided into three administrative units——Kita, Minami, and Tenma. Collectively, those units were referred to as “Osaka’s three districts.” In the mid-eighteenth century, there were 250 neighborhoods in Kita District, 261 in Minami District, and 109 in Tenma District. The neighborhoods affiliated with Kita District are marked with a circle, while those affiliated with Minami District are marked with a red triangle. In contrast, neighborhoods in Tenma District are unmarked.

The sections of the map arranged in a grid-like pattern indicate the location of Osaka’s commoner lands. Those lands were divided into three administrative units——Kita, Minami, and Tenma. Collectively, those units were referred to as “Osaka’s three districts.” In the mid-eighteenth century, there were 250 neighborhoods in Kita District, 261 in Minami District, and 109 in Tenma District. The neighborhoods affiliated with Kita District are marked with a circle, while those affiliated with Minami District are marked with a red triangle. In contrast, neighborhoods in Tenma District are unmarked.

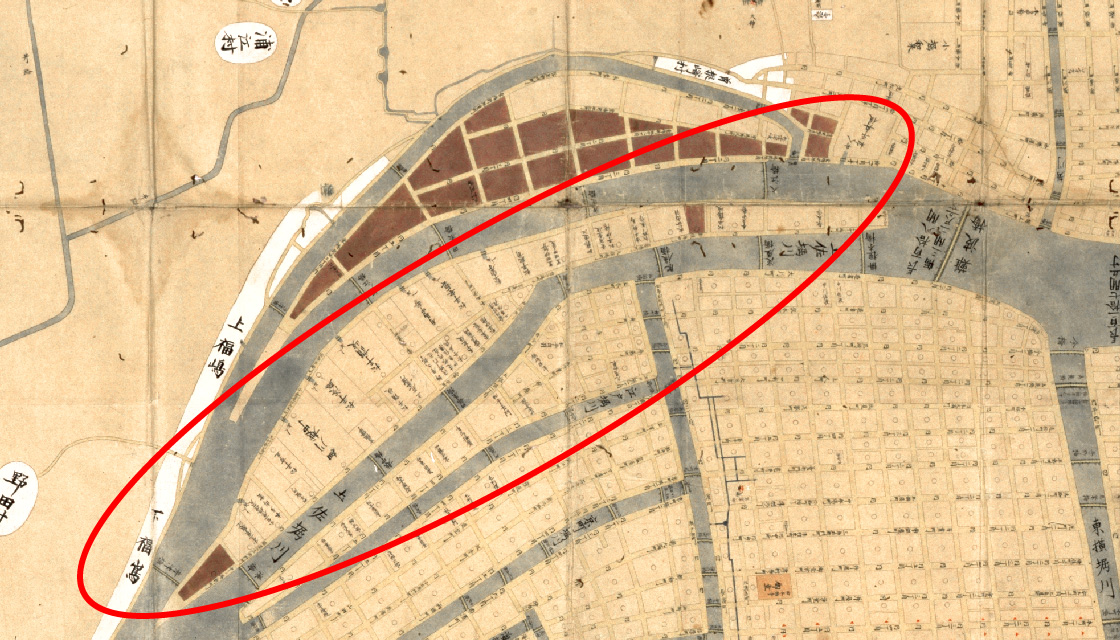

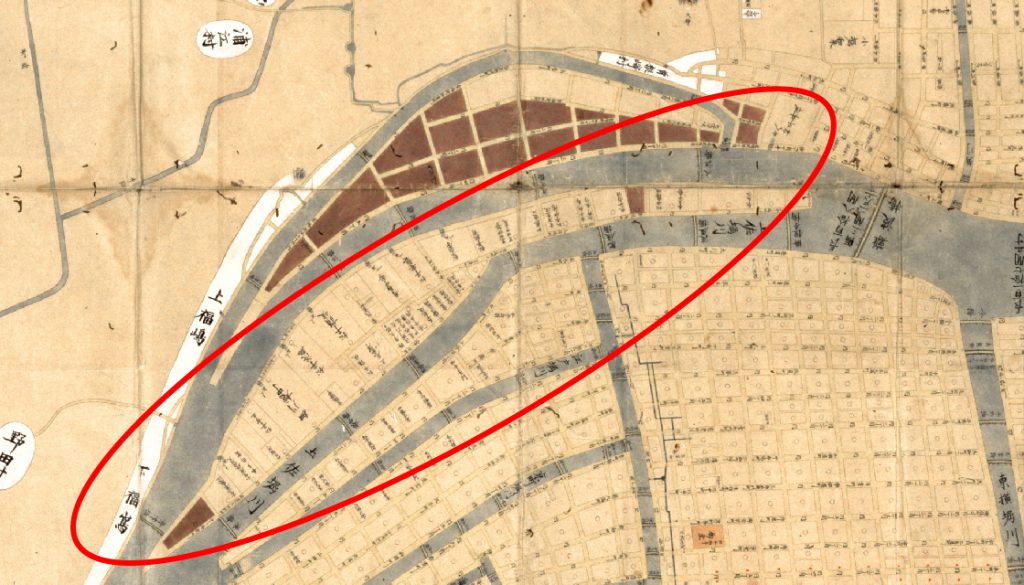

This map was composed during the late-seventeenth century shortly after the construction of the Dōjima-shinchi and Ajigawa-shinchi. Dōjima-shinchi is the area shaded maroon. Several rivers were constructed during this period. One is referred to on the map as the Shin River. However, it later came to be called the Aji River. The areas on both sides of that river are also shaded maroon, indicating the site of the Ajigawa-shinchi.

In addition, the areas identified as Upper and Lower Namba were later transformed into the Horie-shinchi district. Entering the eighteenth century, development continued on the margins of the city with the addition of Sonezaki-shinchi to the north and Dōtonbori and Nishi-kōzu-shinchi to the south. During the next two sessions, we will examine in detail the mode of existence of the urban landowners who were the constituents of Osaka’s neighborhood associations.

Summary

During this session, while examining a seventeenth-century map, we confirmed the geographic extent of early modern Osaka and examined its spatial structure. As we noted, the city area was partitioned based on the principle of status into three broad segments: warrior lands, shrine and temple lands, and commoner lands.

Before concluding, I would like to mention two final points. First, although the city area was partitioned into three broad spatial segments, an examination of urban society reveals a complex social structure. For example, Osaka’s warrior estates and domainal depots commonly maintained client relationships with a wide array of merchants and artisans, who, of course, resided in the city’s commoner districts. Also, when the annually-rotating guard units that defended the castle and city area arrived in Osaka they spent the first few days in lodgings provided by residents of the city’s commoner neighborhoods. In addition, members of the hinin status group and guards who provided security at the city’s playhouses and performance tents also performed official police duties for the City Governor’s Office, while individual city neighborhoods and landholders employed hinin guards to perform a range of tasks. In the case of religious practitioners and performers, as well, we see the existence of complex social networks. As this suggests, conventional descriptions of the early modern status system as a vertically stratified system comprised of the warrior, peasant, artisan, merchant, eta, and hinin status groups fail to capture the actual character of Edo-era society.

Second, early modern Osaka’s spatial composition influenced the spatial structure of modern Osaka. According to a map of 1926 (omitted in this lecture), in the modern period, the area formerly occupied by Osaka Castle and surrounding warrior estates was under military control and served as the site of various military institutions, including a training ground and arms factory. In addition, Nakanoshima, which was the site of the large depots maintained by Western Japanese domainal governments, served as the site of public institutions, such as Osaka City Hall, The Bank of Japan, The Tax Office, The Post Office, school, hospital, and public meeting hall. At the same time, the area was also the location of a major newspaper, as well warehouses and other facilities controlled by large private companies, such as the Sumitomo and Mitsubishi. The comparatively large tracts of land occupied during the Edo period by Western domainal depots were transformed in this way. Temples and shrines, however, remained in place and the city’s commoner neighborhoods, which underwent minor internal changes, retained their overall spatial composition. In contrast, the rural villages surrounding the early modern city underwent a comparatively dramatic change, with the construction of prisons, schools, universities, and factories. During our next session, we will examine the inner workings of early modern Osaka.

この地図は、17世紀・1680年代中頃の大坂を描いたものです。この後、新地開発などで周辺への拡大が見られるものの、ほぼ江戸時代の大坂の広がりを示しています。これを現代の地図と重ねると、JR大阪環状線の北側3分の2ほどに当たります。曽根崎新地の北に大阪駅があります。大阪城の外側を廻って上町台地の東に沿って玉造周辺。南は道頓堀の周辺まで。西側は木津川辺りまでです。

この地図は、17世紀・1680年代中頃の大坂を描いたものです。この後、新地開発などで周辺への拡大が見られるものの、ほぼ江戸時代の大坂の広がりを示しています。これを現代の地図と重ねると、JR大阪環状線の北側3分の2ほどに当たります。曽根崎新地の北に大阪駅があります。大阪城の外側を廻って上町台地の東に沿って玉造周辺。南は道頓堀の周辺まで。西側は木津川辺りまでです。 江戸幕府の直轄都市である大坂には、軍事や警備を担当する城代から定番以下の役職が置かれ、また行政・司法を担当する町奉行が置かれました。大坂城の周辺に、ピ ンク・オレンジ・緑が塗られたところは、大坂城代・玉造口と京橋口の2人の定番の屋敷です。城代は、西国大名を統帥する立場にもあり、数万石の譜代大名が就任するのが普通です。定番は1~2万石の小大名が就きます。これ以外に、1年交替の大番組2組と4人の加番が大坂城警備の任に当たりましたが、これらは大坂城内に居所があったため、この絵図には表現されていません。

江戸幕府の直轄都市である大坂には、軍事や警備を担当する城代から定番以下の役職が置かれ、また行政・司法を担当する町奉行が置かれました。大坂城の周辺に、ピ ンク・オレンジ・緑が塗られたところは、大坂城代・玉造口と京橋口の2人の定番の屋敷です。城代は、西国大名を統帥する立場にもあり、数万石の譜代大名が就任するのが普通です。定番は1~2万石の小大名が就きます。これ以外に、1年交替の大番組2組と4人の加番が大坂城警備の任に当たりましたが、これらは大坂城内に居所があったため、この絵図には表現されていません。 江戸や各地の城下町は、城郭と家臣団の居住する武家地が市域全体の過半を占めるのが一般的ですが、城代と町奉行が置かれた江戸幕府の直轄都市である大坂の場合は、きわめて限定的なのが特徴です。但し、大坂には西国諸藩をはじめとする150余の蔵屋敷がありました。絵図をよく見ると、中之島や土佐堀川の南岸に大名の名前が書きこまれているのが分かります。これは、蔵屋敷なのですが、大坂の場合、江戸の藩邸のように幕府から土地を拝領するのではなく、町人地を購入して、町人の名義人(名代)を置くことになっていました。そのため、大坂に居住する武士身分については、蔵屋敷詰めの藩役人もいたことを念頭に置く必要があります。それでも、部分的ですが・・・。

江戸や各地の城下町は、城郭と家臣団の居住する武家地が市域全体の過半を占めるのが一般的ですが、城代と町奉行が置かれた江戸幕府の直轄都市である大坂の場合は、きわめて限定的なのが特徴です。但し、大坂には西国諸藩をはじめとする150余の蔵屋敷がありました。絵図をよく見ると、中之島や土佐堀川の南岸に大名の名前が書きこまれているのが分かります。これは、蔵屋敷なのですが、大坂の場合、江戸の藩邸のように幕府から土地を拝領するのではなく、町人地を購入して、町人の名義人(名代)を置くことになっていました。そのため、大坂に居住する武士身分については、蔵屋敷詰めの藩役人もいたことを念頭に置く必要があります。それでも、部分的ですが・・・。 絵図中の碁盤目状に道路が通っているところは、町人地です。大坂は、北組・南組・天満組に分かれていましたが、これを合わせて三郷と呼んでいます。18世紀半ばには、北組に250町、南組に261町、天満組に109町がありました。北組の町には○印、南組には赤▲印が記入されていますが、天満組の町は無印です。

絵図中の碁盤目状に道路が通っているところは、町人地です。大坂は、北組・南組・天満組に分かれていましたが、これを合わせて三郷と呼んでいます。18世紀半ばには、北組に250町、南組に261町、天満組に109町がありました。北組の町には○印、南組には赤▲印が記入されていますが、天満組の町は無印です。